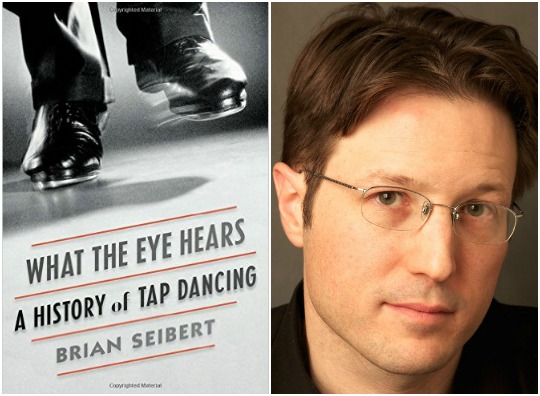

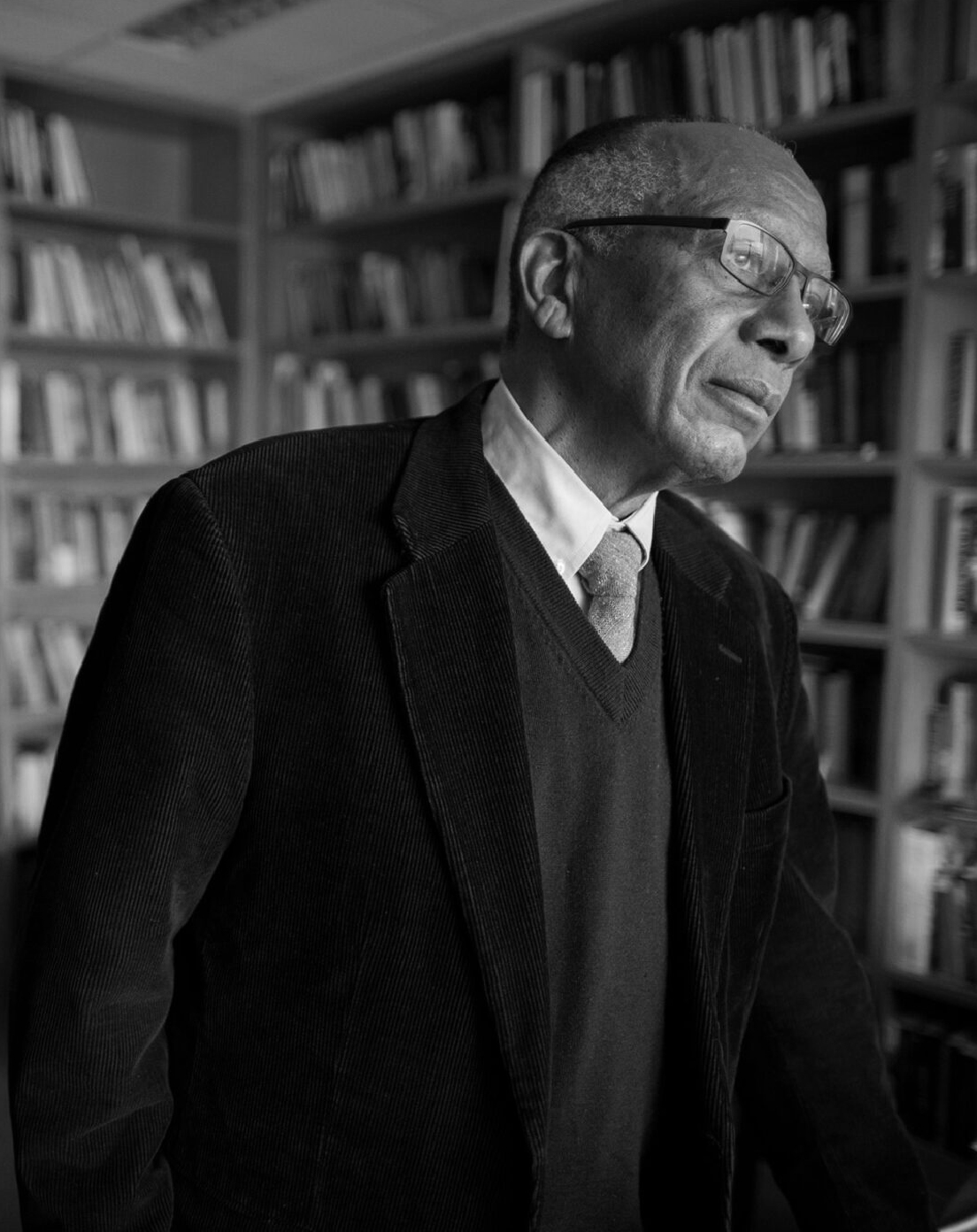

In the 1980s, when Brian Seibert was growing up in suburban Los Angeles, he learned a few basic tap steps in dance class. As an adult in New York City, he came upon Swing 46, a midtown club where a tapper of almost 90 named Buster Brown presided over Crazy Tap Jam, where he opened the floor to all comers, asking “Who’s got their shoes on?”

“And so it was that Brian Seibert, a bespectacled white guy in khakis and a button-down shirt, entered the Swing 46 mix,” he writes in his authoritative, witty and racially nuanced book about a uniquely American art form. He begins with that moment in Swing 46, which threw him into exploring a tradition that “works very hard to create an illusion of ease” and spontaneity, but also illuminates centuries of complex American culture.

What the Eye Hears: A History of Tap Dancing is a revelatory work interested in both assimilation and appropriation. With roots in West Africa and Ireland, early North American versions of this style of dance drew the attention of Charles Dickens and Mark Twain. Seibert, a dancer educated at Yale and Columbia universities, is keenly aware of the trickster in tap, as well as the way the art found its form through minstrelsy, wherein whites imitated blacks.

“What the eye sees is sharpened by what the ear hears,” Seibert writes, quoting dancer Paul Draper. “And the ear hears more clearly that which sight enhances.” Among the many profiles of tap practitioners, the reader meets Jimmy Slyde using his shoulders the way some actors use their eyebrows. And John Bubbles thumping his foot to “emphasize offbeat accents and to ground his more complex syncopations afforded by the tempo.” And the political complexities framing Savion Glover’s solos in “Bring in ‘da Noise, Bring in ‘da Funk.”

Their work argues that it is “possible to play jazz at the highest level with one’s feet.” Still, “compared with tap,” Seibert writes, “both ballet and ‘America’s classical music’ are established, with well-funded institutions and a thick body of professional and amateur scholarship bestowing cultural respect. Tap is much poorer, scrapper, more vulnerable.”

Seibert, a dance critic for the New York Times, has made it less so. He lives with his wife and daughter in Brooklyn, N.Y.