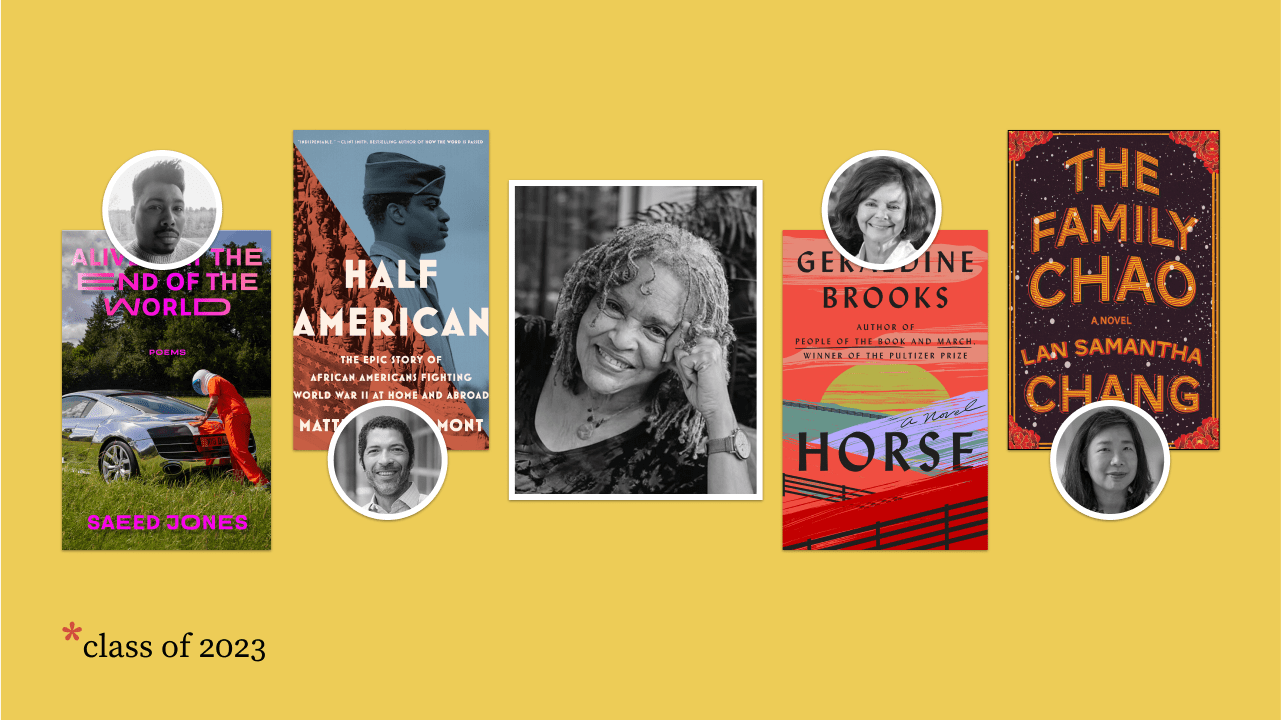

“The Family Chao” is a story of patricide; its plot in delicious parallel with “The Brothers Karamazov.”

“At the center of ‘The Family Chao’ breathes the charismatic Leo Chao, tyrannical father of three American-born sons,” writes Lan Samantha Chang in Pioneer Works of her picaresque and profound book. “Leo is not my father. He’s several shades more malevolent than my father, and he’s also better with money. But I couldn’t have written this book if I hadn’t grown up with my dad. Like Leo, he was a survivor; and like Leo, he was larger than life: a vibrant, strong-willed man with a habit of making blunt remarks.”

Still, it took Chang a dozen years to compose “The Family Chao” amid her responsibilities directing the Iowa Writers Workshop, mentoring and teaching, creating a home with landscape painter Robert Caputo and raising their daughter.

Her novel’s first character, Leo Chao, came to her fully-formed – uncouth, sensual, loud — a Chinese immigrant with three sons and an illegitimate fourth offspring – well before she realized her story could pluck some ripe plot points from Dostoyevsky’s masterpiece, a book Chang first read at age 40. It mesmerized her.

She bifurcates “The Family Chao” into two parts: “They See Themselves” and “The World Sees Them.” The Chaos own and operate a Chinese restaurant in fictional Haven, Wisconsin. “They are noisy and suffering,” Chang told the virtual Barnes & Noble book club. “They’re loud and have jokes and get angry. There is a lot of yelling.”

At the end of the first section, which covers three days around Christmas, Leo Chao is dead, frozen inside the restaurant’s basement refrigerated storage room. In the opening pages, Chang writes, “Now, a year after the shame. . . the community defends its thirty-five-year indifference to the Chao family’s troubles by saying, ‘No one could believe that such good food was cooked by a bad person.’”

In the second half, Dagou, a mercurial man, gifted chef and the oldest son, is on trial for his father’s murder. The courts and neighbors and media crowd in with judgment, and rumors multiply online that the Chaos have eaten the family bulldog.

Chang and her three sisters grew up in Appleton, Wisconsin, where her parents made a home after meeting in New York. Both were born in northern China and survived the Japanese-Sino war. Chang’s father was 30 when he immigrated. He learned English, earned a college degree and became a research engineer; her mother studied psychology and taught piano.

“At some point I realized I had never written about what it was like to grow up in a town like the town where I grew up,” Chang told the book club. “We integrated our town. We arrived in the mid-60s. We had a roller-coaster assimilation in Wisconsin. I learned a lot of complicated things growing up that I’d never put in a book. Once I started, it felt really familiar.”

It also was freeing, Chang said, to write against the model-minority stereotypes. “People have been upset with my book because the characters are not really well-behaved or virtuous.”

Not the jurors of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Joyce Carol Oates called the novel “an outstanding work of fiction,” saying she had read nothing else of late as ambitious or accomplished. Rita Dove enjoyed the book’s multi-faceted nature and the way it “digs deep, with a capacious reach.”

The book offers heartbreak, comedy and suspense, and is, said Miwa Messer of the podcast “Poured Over,” an important post-immigrant novel. It has a lot to say about ABCs or American-born Chinese. It has a lot to say about food.

Writing in “Food & Wine” magazine, Chang recollects, “When my parents began to find American friends, my mother started keeping a file card in her recipe box with two lists of dishes: What do Americans like? What don’t Americans like?

“She learned quickly: Americans liked beef. They devoured her hong shao niu rou (red-stewed beef) and preferred their soy sauce with a little sugar in it. They liked peanut butter — even combined with soy sauce. But they were confused and put off by a Chinese staple with a similar texture: fermented tofu.”

In the novel, the Chaos make a similar list. Chang also writes about class and masculinity; the book evokes Richard Russo’s fiction. She said that like John Irving, she depended on the plot scaffolding to pull her along even as she delights in discovering what her characters will do. While working on the book, both of Chang’s parents died. Her father was 97.

There were times, Chang wrote, when he seemed immortal. He had put all four daughters through Ivy League colleges. Chang has degrees from Yale and Harvard universities and has won numerous fellowships.

In her acknowledgments, Chang writes, “I’m indebted to all my students over the last fifteen years. They have been profound, gifted, and kind. I appreciate their patience with me and their acceptance of my shyness, bluntness, and inadequacy.” Asked by a reader to sum up her advice, Chang smiled and said, “Don’t assume you know the people at the restaurant.”