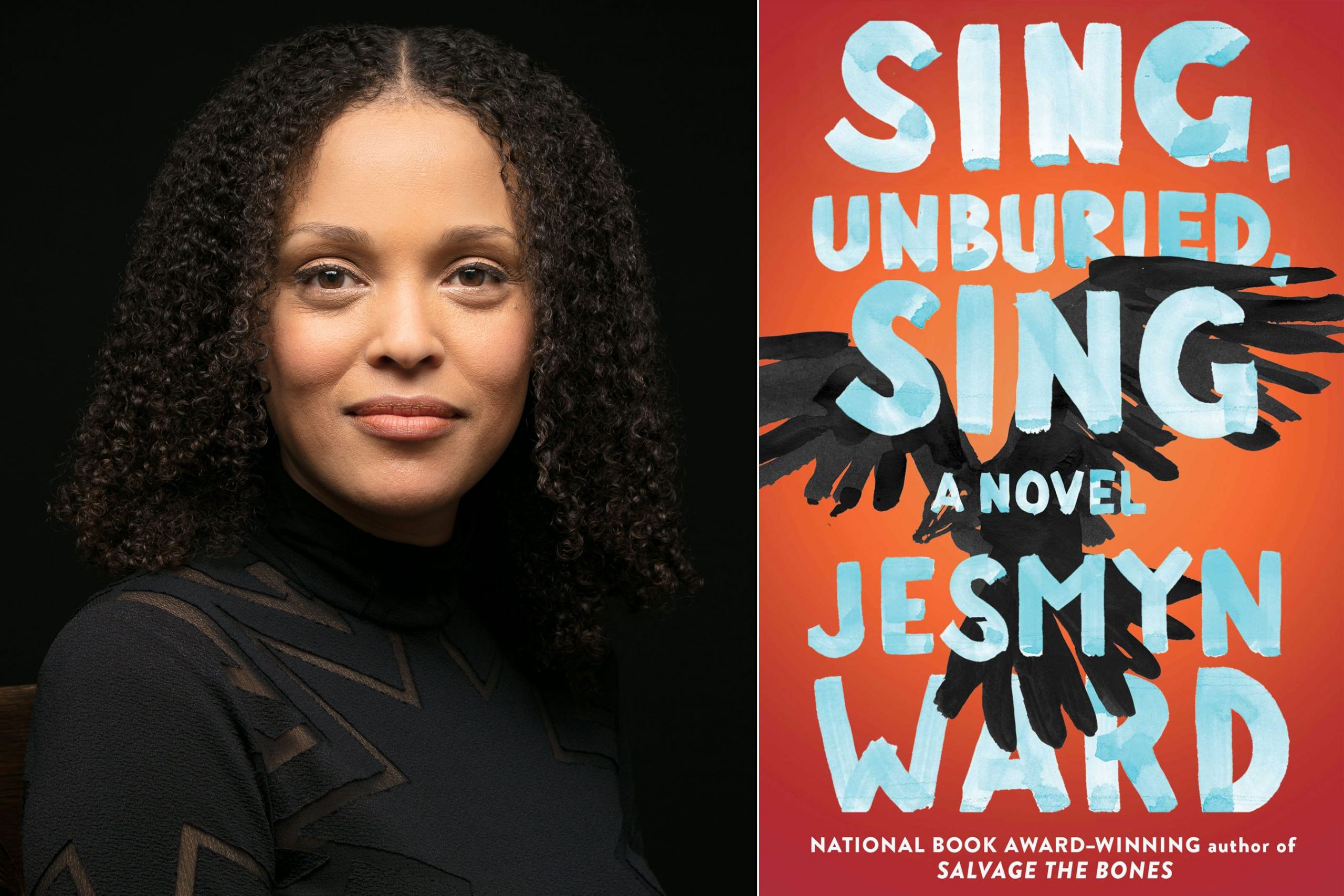

The novels of Jesmyn Ward create a fictional place – Bois Sauvage – rooted in her rural hometown on the Gulf Coast of Mississippi. The vividness of Bois Sauvage and its inhabitants has provoked critical hosannas, and comparisons to William Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County. The ghosts in Ward’s most recent novel – Sing, Unburied, Sing – evoke the hauntings found on many of Toni Morrison’s pages.

“Growing up in DeLisle, Mississippi has influenced me in many ways,” Ward told the MacArthur Foundation, which awarded her a fellowship last year. “Growing up here taught me to appreciate beauty, the beauty of the bayous and of the forests and of the Gulf. Growing up in this community taught me to appreciate storytelling, taught me to appreciate language.”

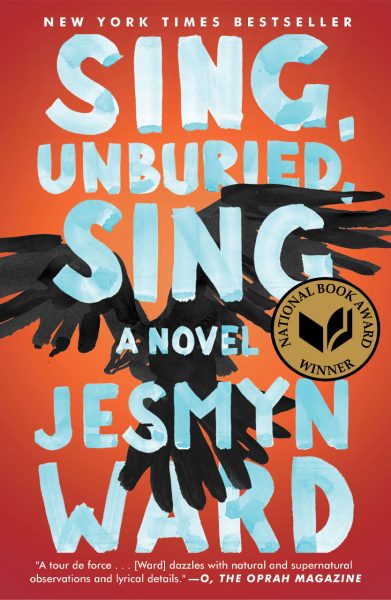

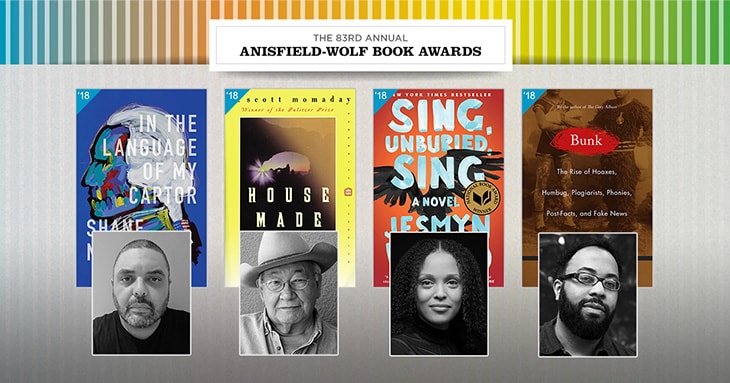

That appreciation burnished Sing, Unburied, Sing into what Anisfield-Wolf juror Joyce Carol Oates calls “a beautifully rendered, heartbreaking, savage and tender novel, a tour de force of exquisite language in the service of honoring the dignity and worth of its memorable cast of children, women and men.”

The story centers on Jojo, turning 13 as the novel opens and trying to understand what it means to be a man. His black grandfather, Pop, is one source; his white grandfather, who won’t acknowledge him, is another. Jojo’s own father, Michael, is being released from prison, so his drug-addled mother, Leonie, packs the family and a friend into a car to head north to Mississippi’s notorious Parchman Farm, the state penitentiary. Sing, Unburied, Sing becomes a road book and a ghost story and a tale of sibling love. It won Ward her second National Book Award in November. She is the only woman in American letters to have two.

“I feel like in every book that I commit to telling the truth about the place that I live in, and also about the kind of people who live in my community,” Ward said on the radio show Fresh Air.

Growing up, young Jesmyn wore hand-me-down clothes and ate meals stretched by food stamps. When her father lost his job at the local glass factory, her family moved in with Ward’s maternal grandmother. Fourteen people wedged into the house – Jesmyn, her parents, two sisters and a brother, a cousin, her grandmother’s four sons and three daughters, plus the matriarch herself. “It was the first and only time I lived with so many people I loved,” Ward said.

Ward’s mother worked as a maid. Her employer recognized a spark in 11-year-old Jesmyn and offered to pay for her private school tuition. A senior year essay led to Stanford University, where she earned a B.A., then an M.A., then an M.F.A. from the University of Michigan. When Ward’s first novel came and went without much stir, she turned her thoughts toward nursing school.

But in October 2000, when a drunk driver killed Ward’s teenage brother Joshua, she re-dedicated herself to writing. It led to memorializing Joshua Ward in Men We Reaped, along with four other black men in their circle who died young.

After Ward won her first National Book Award in 2011 for Salvage the Bones, a novel set on the Mississippi Gulf during the days leading up to Hurricane Katrina, the recognition helped her land a professorship at the University of South Alabama, then Tulane University.

“The word ‘salvage’ is so close to ‘savage,’” Ward said in 2014 at the Cleveland Public Library. “It connotes resilience, fierceness and courage.” She described her novel’s pregnant, 15-year-old narrator, Esch Batiste, brushing off the ants and standing up after the hurricane as the only thing she could do. “This is savage,” Ward said, “you make a future from it, you tell your story, you survive.”

The writer said that when Katrina hit her own family, she swam to escape alongside her pregnant sister. The Wards sheltered in a tractor in an open field during a Category 5 hurricane, she said, while a white farm family refused to take them in. Another family down the road eventually helped them.

Ward, her partner, their young daughter and son still make their home in rural Mississippi. She told an audience in November that she will continue to tell stories rooted in this Southern soil.

“I hope people who read my books perhaps feel empathy for us,” she said, “and really see us for a complicated people.”