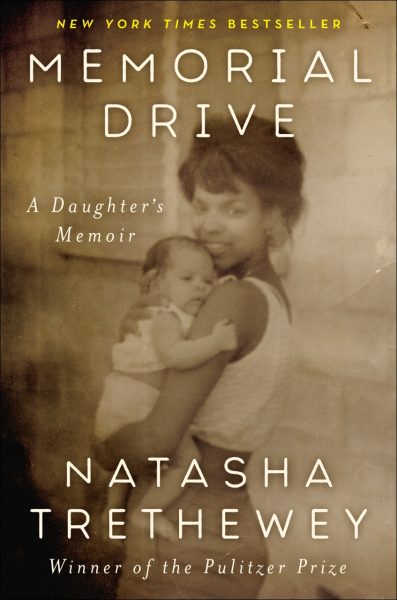

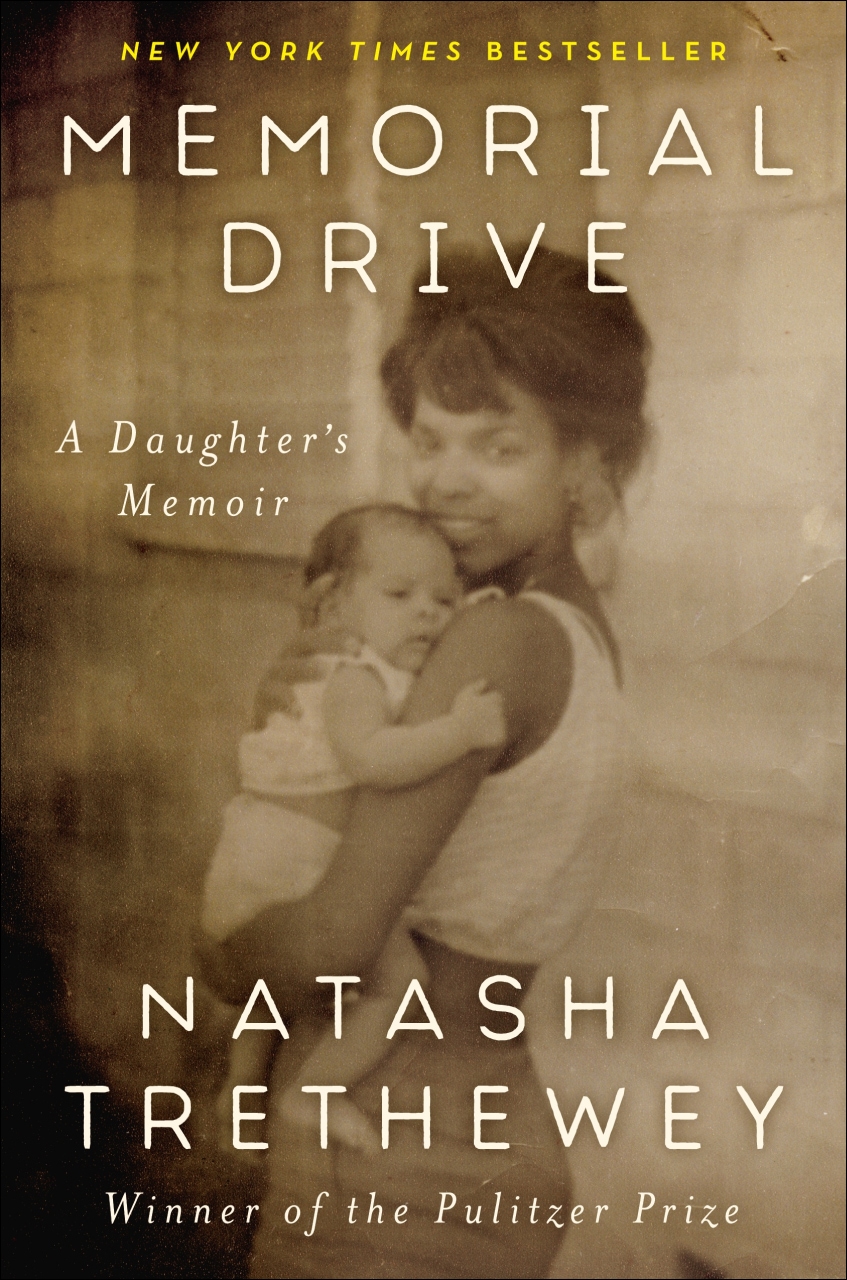

In the final paragraph of Memorial Drive, Natasha Trethewey describes driving with her mother toward Gulfport, Mississippi, where their relationship began in 1966 when Natasha was born.

“Often, when I am alone on the road, I think of traveling back to Mississippi each summer with my mother,” Trethewey writes. “The year before I was old enough to drive, she let me practice steering the car on long stretches of empty highway. I’d reach across the center console and take the wheel, leaning into her, my back against her chest, following the arc of the sun west toward home. For several miles we’d drive like that: so close we seemed conjoined, and I could feel her heart beating against me if as if I had not one, but two.”

The former U.S. Poet Laureate’s Memorial Drive is her testimony, embrace, remembrance and investigation of the life and death of her mother, née Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough. In 1985, a man she had fled, divorced and sought to escape – via the police and the courts – killed her. He shot her, the personnel director for human resources at the county mental health agency, in an Atlanta parking lot on Memorial Drive. She was 40. Her daughter was 19.

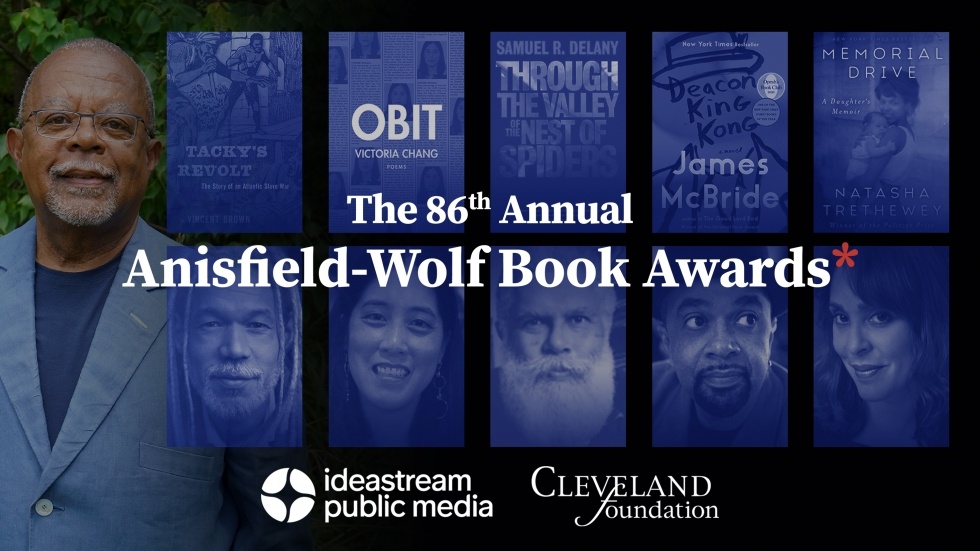

As Trethewey rose in prominence – she won a Pulitzer Prize in 2007 for “Native Guard” and served as the nation’s 19th poet laureate from 2012-2014 – she noticed a distressing pattern.

“Whenever I was written about, my backstory became part of the story,” she told Isaac Chotiner of the New Yorker. “When my backstory was written, my mother entered it only as a footnote, or an afterthought – as simply a ‘victim’ or ‘murdered woman.’ It really hurt me because her role in my life, in me becoming a writer, was being diminished or erased. I just decided that if she was going to get mentioned then I was going to be the one to tell her story, and to put the important role she played in my making in its proper context.”

Trethewey (pronounced TRETH-eh-way) was the only child of Turnbough and Eric Trethewey, a Nova Scotia-born poet who met young Gwen in a college literature class on modern drama. They eloped to Ohio in 1965 – their union still illegal through much of the South. The marriage certificate lists the groom’s race as “Canadian” and the bride’s as “colored.”

Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards Juror Simon Schama describes the prose in Trethewey’s memoir as “intensely poetic, but with an emotional economy that makes the gathering catastrophe even more overwhelming when it unfolds. I also want to stress her book is a compelling portrait of race in America, from the 1960s on. It’s a thrilling addition to American literature that will be read for many, many years to come as a classic not just of the memoir genre but any kind of contemporary writing.”

The intersection of history and geography animates all Trethewey’s books. In one poem she writes, “The ghost of history lies down beside me/ rolls over, pins me beneath a heavy arm.” In “Native Guard,” Trethewey tells the story of a Black Louisiana regiment that watched over captured Confederates during the Civil War.

“My birthday is April 26th, Confederate Memorial Day,” she told the New York Times. “I was born 100 years to the day after that holiday was invented. I don’t think I could have escaped learning about the Civil War and what it represented.”

In Memorial Drive, Trethewey explores how she embodies some of the war’s persistent contradictions.

In 2005, when she and her husband both taught at Emory University, they left their house and walked to a restaurant on the square in Decatur, Georgia. It is just blocks from the DeKalb County Courthouse where Gwendolyn Turnbough’s killer was convicted. Trethewey describes the scene near the end of her book.

A stranger struck up a conversation with her, then stunned Trethewey by asking if she was indeed her mother’s daughter. He had been the first policeman on the scene of the murder, and 20 years later, broke down in tears. He also told Trethewey that the courthouse would be purging its records of the case. He offered to save them for her. The transcripts and evidence – including a long diary entry from her mother’s briefcase that Trethewey had never seen – form key sections of Memorial Drive.

“I think I have two existential wounds that made me a writer,” Trethewey told the New Yorker. “And one of them is that great loss. I think it is my deepest wound, losing my mother, but the other one is the wound of history that has everything to do with being born Black and biracial in a place that would render me illegitimate in the eyes of the law, a place that tried to remind Black people for centuries of our second-class status with Confederate monuments, with the Confederate flag, with Jim Crow laws, with all sorts of things that are part of our shared history as Americans. And those two wounds are deep and linked for me.”

Trethewey married historian Brett Gadsden in 1998. They both serve on the faculty of Northwestern University and live outside Chicago.

Memorial Drive