Tiya Miles grew up in Cincinnati listening to family stories, a practice that whetted her appetite for history, sparked her scholarship and led eventually to a MacArthur “genius” grant and a faculty position at Harvard University.

“I think the way in which I approach history comes from times I spent with my grandmother when I was a girl,” Miles told Krista Tippett for “On Being” in 2012. “When I was very young, my mother and I lived with my grandparents. And my grandmother was one of those women who just loved to tell stories. . . I recall especially the stories she told about living in Mississippi, coming north during the Great Migration, and the struggles that she faces as an African American woman, single mother, and domestic worker. Hearing how my grandmother felt so tied to her past, how she was always on that Mississippi farm that she grew up on, and in the city at the same time, influenced the way I think about the past and how near it feels to me.”

On her website, Miles describes her grandmother, Alice Stribling Banks, as “the most brilliant person I have ever known.”

Decades into her career, Miles gave a talk in Savannah, Ga., where she was button-holed by a stranger who asked if she “knew Ashley’s sack.” Something about his urgency drew Miles’ attention. She opened a subsequent email from him that contained an image of a plain cotton sack, with these ten lines of embroidery:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

The cotton tote, partly stained but clearly legible, had surfaced in 2007 at a flea market outside Nashville. A shopper recognized its value and bought it, along with the other rags in the bin, for $20. Miles was able to see it on display at the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

“I felt compelled to write about it,” Miles said during a 2021 Harvard Radcliffe Institute talk. “It was so beautiful and terrible and concentrated and real, that I almost felt like I could fall into it. So, I changed my plans for a book that I wanted to write next.”

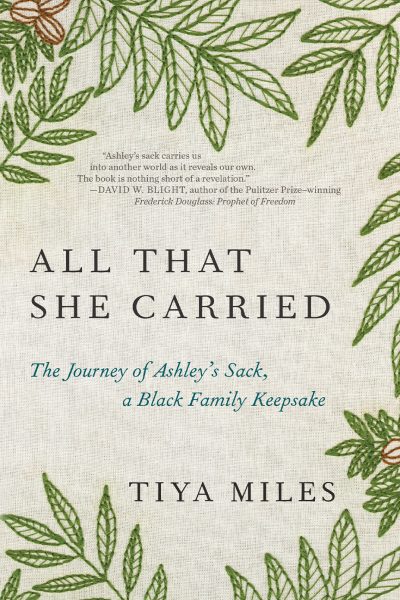

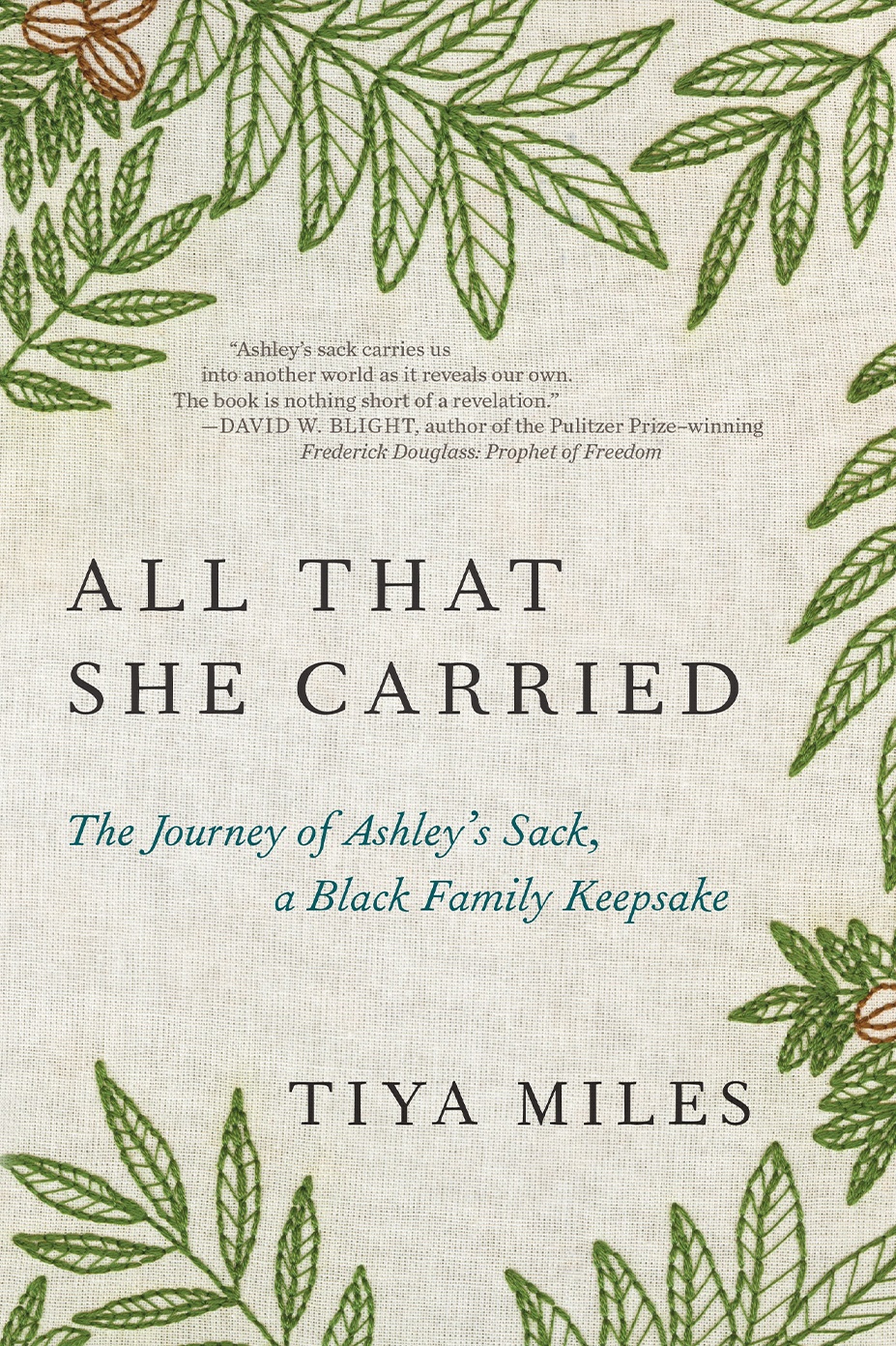

The result is “All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake,” Miles’ sixth book and one of the most lauded titles of 2021. It centers the love and creativity of a Rose packing an emergency parcel for a daughter she would not see again.

Miles stresses that Rose’s choices covered food, clothing, and shelter: pecans are nutrient-dense and were valuable enough to trade; a spare dress and the sack itself that was big enough so a 9-year-old could climb inside or improvise it into a barrier in the rain. The braid served as a spiritual connector between mother and daughter, as well as a tangible sign of Rose’s autonomy.

“Technically, Rose didn’t own her hair – she didn’t own her body; her enslaver did,” Miles said at the Radcliffe lecture. “So, for Rose to actually cut her own hair and give it to her daughter meant taking possession of her own body.” The gift “represented the message of that independence, that was being conveyed to Ashley.”

As a scholar, Miles needed her own resourcefulness to surmount the paucity of documents about Rose and Ashley and Black women in bondage. It would be unethical, Miles said, to default to the perspective of the enslavers. So, she built her text out of careful research: the sack, she notes, “is at once a container, carrier, textile, art piece and record of past events.”

Miles layers in historical letters, photographs, and oral histories from women of the period, and about Charleston itself, as well as the material history of cotton. She read widely in the literature that imagines Black women’s lives during the eras in question.

The result, notes Annette Gordon-Reed, an Anisfield-Wolf winning historian, “is a brilliant exercise in historical excavation and recovery, a successful strike against the traditional archives’ erasure of the lives of enslaved African-American women.”

Anisfield-Wolf Juror, historian Simon Schama, said the book “made me think in fresh ways about this long and difficult and challenging history. I’m very grateful to Tiya Miles for allowing us all to read this quite beautiful and important book.”

Miles earned a degree in Afro-American studies from Harvard, a master’s in women’s studies from Emory University and a doctorate in American studies at the University of Minnesota.

In the interview with Tippett, Miles said, “I’m thinking now about this wonderful line at the end of Toni Morrison’s ‘Beloved,’ which is really influential for me in thinking about my scholarship. This is the line where the narrator says this was not a story to pass on. You can read that in two ways: You can read that this was not a story to tell again, to pass on, or this was not a story to be missed. I think that these kinds of stories that my grandmother told me, you heard from your family history, have both those elements in them. We need them, we want to explore them and yet we know that, in some ways they might be dangerous.”

Miles and her husband, the scholar Joseph P. Gone, live in Cambridge, Mass., with their three children.