Cultural critic Daniel Mendelsohn paused in Cleveland this October before his written remarks to take in the stunning, restored Temple-Tifereth Israel, repurposed at the heart of a new Maltz Performing Arts Center.

A month earlier, the richly glowing Silver Hall reopened its doors with a performance from the Cleveland Orchestra, occupying the stage where Mendelsohn stood. The musicians played “The Creatures of Prometheus” and “Leonore,” both overtures from Beethoven, on 26 instruments rescued from the Holocaust.

“I am dazzled by the space we are all sitting in,” said Mendelsohn, gesturing toward the burnished wood and subdued golds. The auditorium reminded him of the ruined beauty of many Eastern European synagogues, abandoned with “trees growing in the middle of them now.”

He also wryly noted, as a platter of pink shrimp hors d’oeuvres shimmered past during the faculty reception, “It’s not a synagogue anymore.”

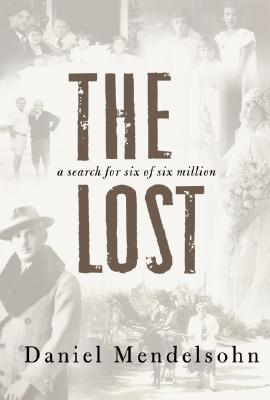

The celebrated writer, a classicist whose essays appear in the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, traveled extensively for five years, visiting Ukraine, Poland and Lithuania, as well as Israel, Sweden, Denmark and Australia, to report his much-honored memoir, “The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million.”

Eli Wiesel reviewed the book in the Washington Post nine years ago, finding it “rigorous in its search for truth, at once tender and exacting.” The New York Times praised its meditations on conflicting ways of storytelling, a thread that Mendelsohn took up in his Cleveland remarks, “’Lost’ Between Memory and History: Writing the Holocaust for the Next Generation.”

The six relatives in Mendelsohn’s subtitle were a maternal great-uncle, Schmeil Jager, his wife Ester and their four teenage daughters: Lorcka, Frydka, Ruchele and Bronia. For more than three centuries, the family had lived in “a small, pre-Carpathian Polish town” called Bolechow, now part of Ukraine.

The reader enters “The Lost” through the youthful sensibilities of young Daniel, who grew up enthralled by his snappily-dressed, successful grandfather, and who spent part of his childhood provoking tears in Florida from certain elderly European Jews: the great nephew so closely resembled Schmeil. A handful of surviving photos of Jager, reprinted in “The Lost,” capture a strong echo between the two men’s eyes, mouth and posture.

When the Germans marched into Bolechow in July 1941, some 6,000 Jews called it home. In August 1944, as the Soviets’ army arrived, “48 survivors emerged from the forest, the cellars, the haystacks where they had been hiding.”

Some sixty years later, Mendelsohn began searching for this remnant. He also discovered the names of his six relatives in the Yad Vashem database for Shoah victims. Yet the archival information turned out to be “wrong, all wrong, the spelling of names, the dates of births and deaths, the spelling of parents’ names.”

“Why does this matter?” he asked. “It matters to me precisely because we are in a hinge moment: still close enough to care about small things, small inaccuracies that depart from the truth. But in 2000 years, will it matter that a young woman died at 21, not 18? That large events are made of small details?”

Mendelsohn, 55, is deeply interested in the moral drift inherent in storytelling. He is keenly aware that that his own experience – writing “The Lost” – moved what happened into “the story of what happened.”

Mendelsohn, 55, is deeply interested in the moral drift inherent in storytelling. He is keenly aware that that his own experience – writing “The Lost” – moved what happened into “the story of what happened.”

The book’s raw material was a fragment of a welter of stories – belonging to “perpetrators, victims, neighbors, survivors.” One such survivor kept her secrets. Meg Grossbard told Mendelsohn, “You think you deserve to know all this because it’s part of ‘history.’ This wasn’t history to me. This was my life. And my life belongs to me . . . If I tell you my story, it will become your story.”

With the perspective of a classicist, Mendelsohn asked his audience – gathered for the first ThinkForum of the academic year – to consider how catastrophic and complex Jewish slavery in Egypt was, now boiled down into the Haggadah, stories reduced to a ritual two hours.

“We today are too close to the Holocaust to assess what it will mean,” he said. “My own, seemingly big book, is not but a grain of sand. In 2,000 years, Lorcka will have disappeared.”

Mendelsohn seems reconciled to this notion. “People of the future will need room to live their own lives.”