Ten years after Edith Anisfield Wolf established the book prizes, Soviet troops advanced across southeastern Poland and liberated Auschwitz, the complex were 1.3 million were enslaved — and 1.1 million murdered — during the Second World War.

Did the prominent Jewish Clevelander with family in Austria ask herself in 1945, “In the face of such decimation, what good is a book award?”

Seventy-five years after the fact of Auschwitz was laid bare to the world, “attacking Jews has once again become socially acceptable in many countries – across the left-right ideological spectrum, and among groups that blame Jews for their grievances and oppression” writes Dr. Walter Reich, former director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, in the Atlantic Monthly.

He attributes this resurgence to diminishing general knowledge of the Holocaust. “The horrifying knowledge of where anti-Semitism can lead,” he writes, “has been, in large measure, lost in a miasma of forgetting, ignorance, denial, confusion, appropriation, and obfuscation.”

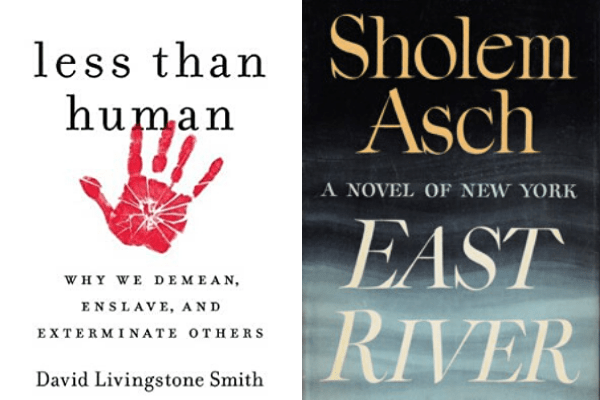

In her classes at Case Western Reserve University, Dr. Lisa Nielson, an Anisfield-Wolf scholar, often teaches two writers in the canon: philosopher David Livingstone Smith and the Yiddish novelist Sholem Asch.

In 2012, Smith won his prize for “Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others” and Asch — a Polish-born immigrant to the United States — for his 1947 novel “East River.”

“Smith has some grim and important stuff to say about the Holocaust, and Sholem Asch is a great pairing,” Nielson writes. “Asch has a devastating short story about identity, dehumanization and survival called ‘Heil, Hitler!’ that is a powerful — if hard for some — choice to read.”

In “Less Than Human,” Smith writes, “For most readers of this book, the word genocide is probably synonymous with Auschwitz. The Holocaust was the paradigmatic twentieth-century genocide, and is also the most thoroughly documented one. These is an immense literature describing how Germans of the Third Reich thought of Jews, as well as Slavs and Gypsies, as less than human, portraying them as apes, pigs, rats, worms, bacilli, and other nonhuman creatures. And it is abundantly clear from this evidence that the Nazis did not intend the term subhuman to be taken metaphorically.”

“’One does not hunt rats with a revolver,’ quipped one SS expert, in a chilling allusion to the mass exterminations, ‘but with poison and gas.’”

Standing between the Nazis and the “degenerate Jew” propaganda was the fiction and plays of Asch. In 1933, Nazi students at more than 30 German universities pillaged libraries in search of titles they considered “un-German.” Among those thrown into the flames were the books of Sholem Asch.

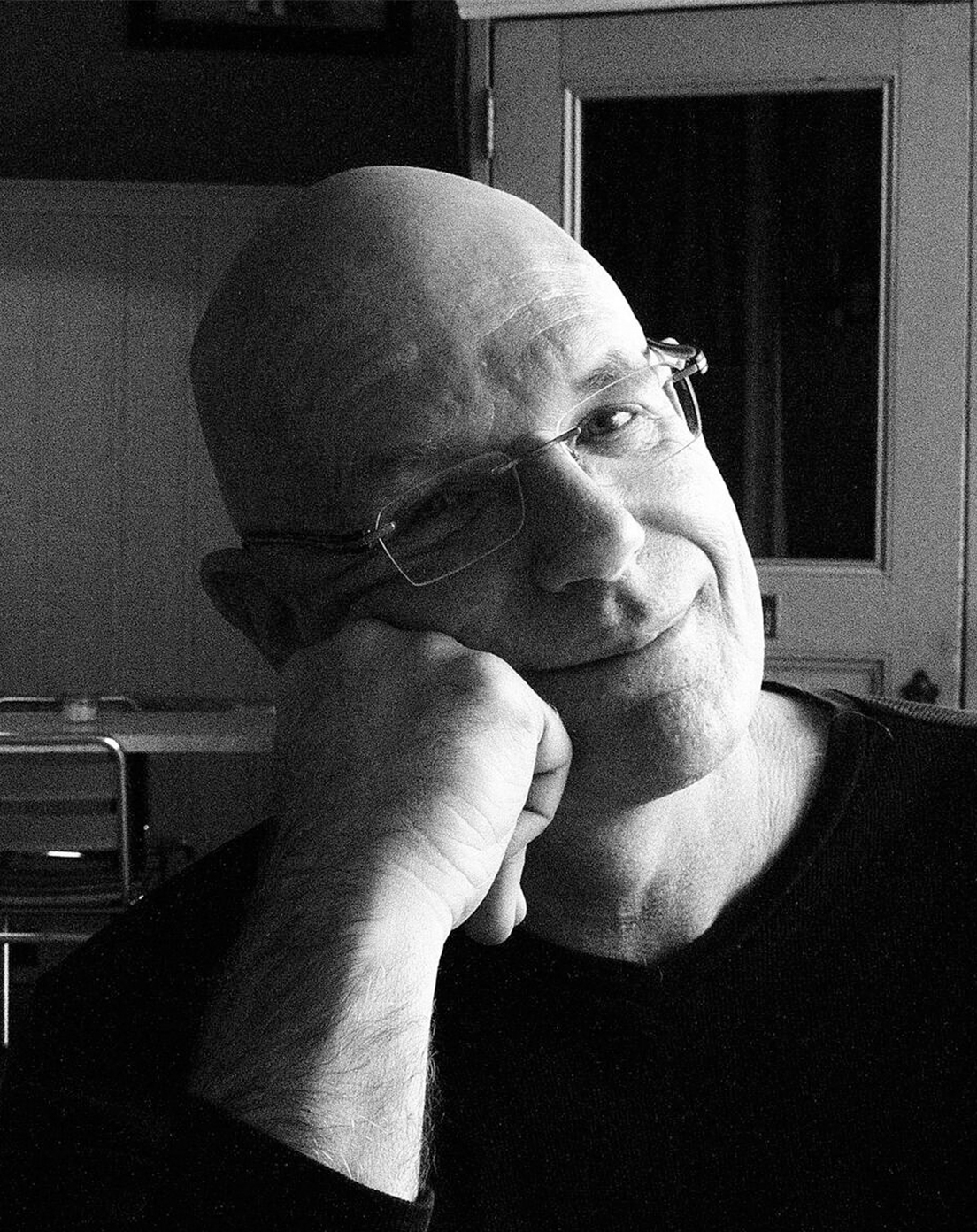

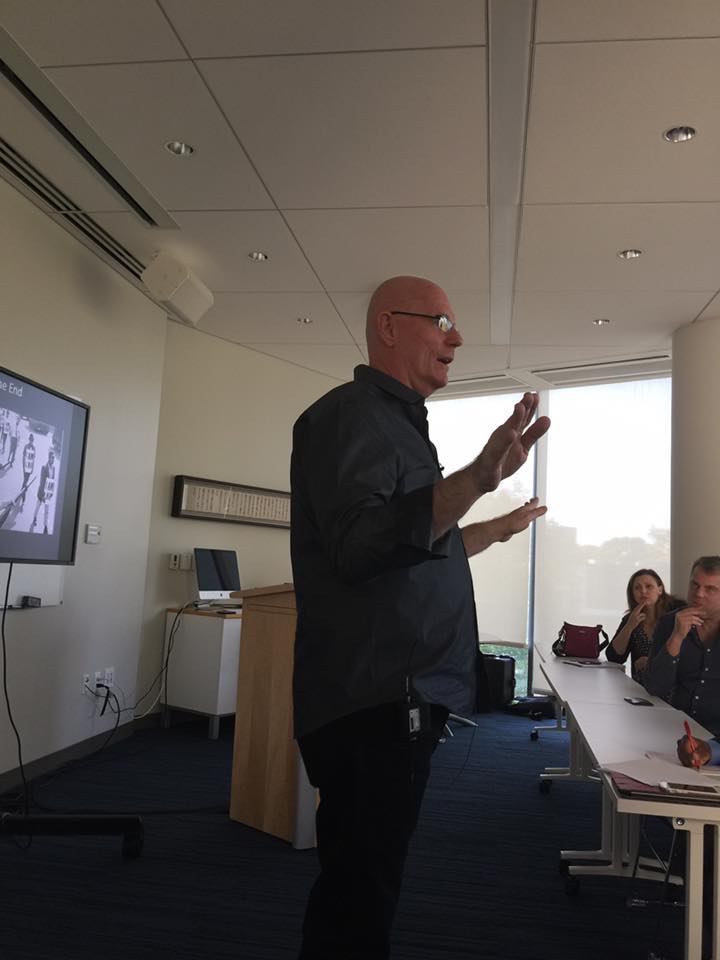

Philosopher David Livingstone Smith gave a lively preview of “Making Monsters: The Uncanny Powers of Dehumanization,” his forthcoming book, for an avid circle of listeners gathered at the Inamori Center for Ethics and Excellence in Cleveland.

Philosopher David Livingstone Smith gave a lively preview of “Making Monsters: The Uncanny Powers of Dehumanization,” his forthcoming book, for an avid circle of listeners gathered at the Inamori Center for Ethics and Excellence in Cleveland.

The new work examines two cases of spectacle lynching – public events for which railroads put on extra excursion cars, tens of thousands assembled and crowds fought for human relics and nightmarish photos to commemorate the torture and killing of young black men.

Smith, 63, is keen to know “what is going on under the hood here, in these acts pursued by sane, ordinary people…the same sort of folk you’d meet at an average PTA meeting.”

The scholar, a professor at the University of New England, blends an examination of biology, philosophy, language and psychology. He won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2012 for “Less than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others.” Quite cheerfully, he called attention to critiques of this landmark book, ideas which have helped refine his current thinking. Smith defines dehumanization as “conceiving of others – whole groups – as subhuman creatures.”

One critique came from philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah, another Anisfield-Wolf winner, who suggested that the lethal violence perpetrators direct at others is actually an acknowledgement of their target’s very humanity. Such fury is only directed against someone capable of agency — that is moral reasoning.

“Virtually every genocide that I know anything about has been a racialized genocide,” Smith has said. “The notion of race gets us into a lot of trouble.” He told his Cleveland audience that “racializing a group of people is halfway to dehumanization.”

A warm, casually dressed man who is rigorous about definitions, Smith was frequently wry and very comfortable telling questioners when he didn’t know. He participated in a thought-provoking panel on combating dehumanization with Shannon E. French, a military ethics expert who directs the Inamori Center at Case Western Reserve University, and Dalindyebo Shabalala, a specialist in environmental law and the intellectual property rights of indigenous peoples. He is a visiting professor at the Case law school.

“The death penalty in the United States is fundamentally racialized – its roots are in slavery and violent law enforcement,” Shabalala said. “It comes from a story we tell about those getting the death penalty, one that is centered on the black male threat.”

French, whose book “The Code of the Warrior: Exploring Warrior Values Past and Present” was updated and reissued this fall, argued that Tamir Rice would not have died if Cleveland police had adhered to military standards. Fear for one’s own life is no justification for opening fire among soldiers, she said, particularly in an instance when the boy had no gun. “We need a warrior’s code in the police department,” she said.

Shabalala was skeptical that a code of honor could be restored to modern warfare, but French argued that some U.S. generals had insisted on respecting Iraqi culture and people when American forces invaded, and that an alertness to the code among chaplains and others has prevented some atrocities.

When pressed on how to combat dehumanization, Smith called for improved education on our delusions about race. He stressed that we must face “the full extent of our national crimes. I think that would free us in a lot of ways.”

This spring, as Rwanda commemorates the 1994 genocide that extinguished more than a million of its citizens, a nation assesses its reconstruction while the wider world wrestles with the fact that it stood by. Several important books illuminate these tasks.

“Twenty years ago today our country fell into deep ditches of darkness,” said Louise Mushikiwabo, Rwanda’s current minister of foreign affairs. “Twenty years later, today, we are a country united and a nation elevated.”

Economic progress and a fragile peace characterize Rwanda now, under a new Constitution and a marked ascendancy of women into leadership. A moving photographic portrait of the hard work of reconciliation is newly published in the New York Times.

“The story of U.S. policy during the genocide in Rwanda is not a story of willful complicity with evil,” wrote Samantha Power in 2001, in her now-landmark essay, Bystanders to Genocide. “U.S. officials did not sit around and conspire to allow genocide to happen. But whatever their convictions about ‘never again,’ many of them did sit around, and they most certainly did allow genocide to happen.”

This startling essay expanded into Power’s book, “A Problem from Hell: America in the Age of Genocide,” which won both the 2003 Anisfield-Wolf Book award for nonfiction and a Pulitzer Prize.

The book is a meticulously researched portrait of U.S. inaction throughout the 20thcentury – despite the growth of human rights groups, the advent of instant communications and the erection of the Holocaust Museum on the Mall in Washington, D.C. “Rwandan Hutus in 1994 could freely, joyfully and systematically slaughter 8,000 Tutsis a day for 100 days without any foreign interference,” Power writes.

All the while, the Clinton Administration blocked deployment of U.N. peacekeepers, worked actively in diplomatic circles to suppress the “G-word” (genocide) and “refused to use its technology to jam radio broadcasts that were a crucial instrument in the coordination and perpetuation of the genocide,” Power writes.

In “Less than Human,” David Livingstone Smith picks up on these radio broadcasts as essential fodder to the dehumanization that made the Rwandan genocide possible. His book won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2012, and is the basic text for the Anisfield-Wolf course at Case Western Reserve University: Reading Social Justice.

As the world remembers the antithesis of social justice – wholesale butchery of a people – both Power and Smith exemplify how sober scholarship can illustrate the circumstances that unleash new killing fields. Smith is a professor of philosophy at the University of New England; Power has become the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations.

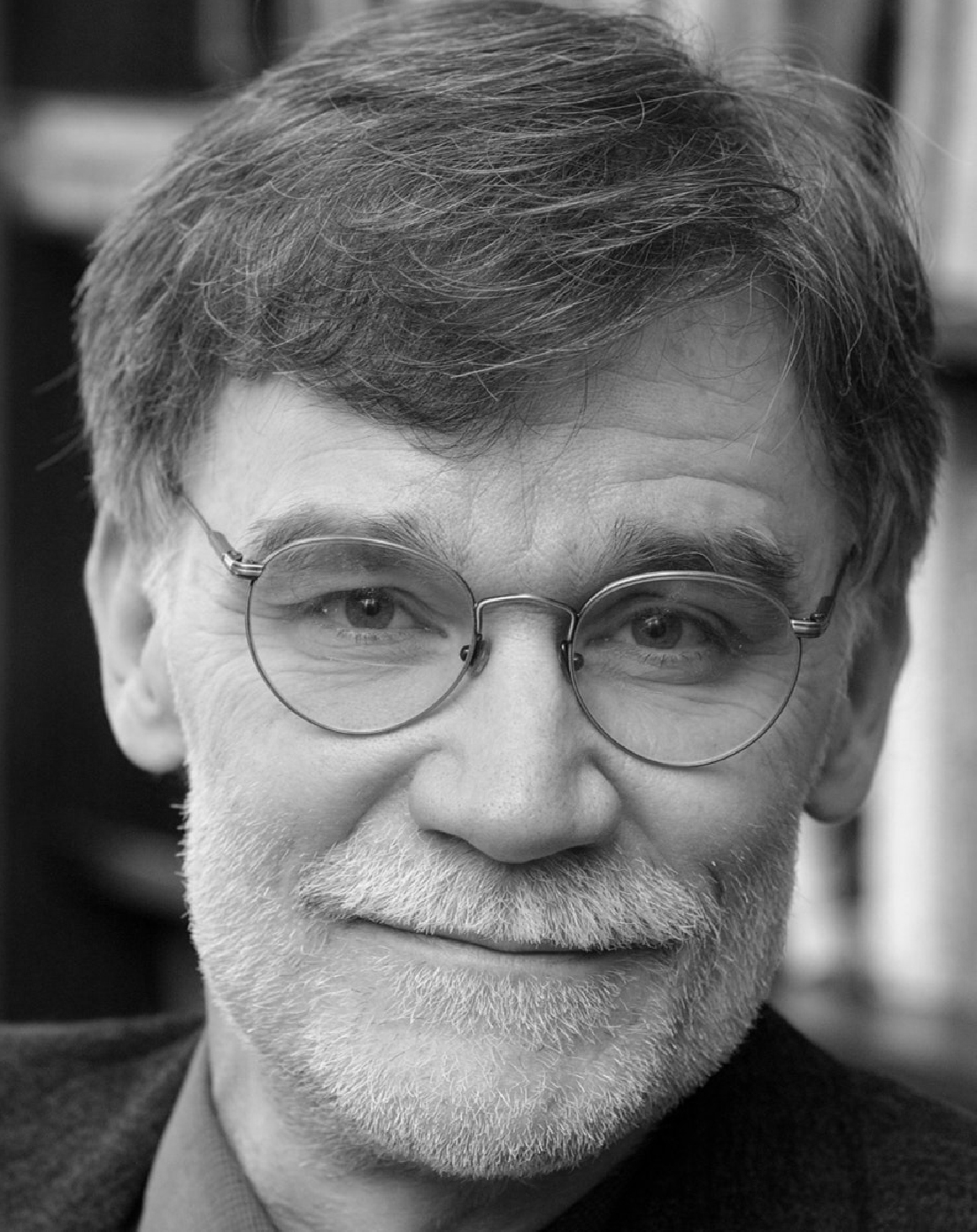

Philosophy Professor David Livingstone Smith kicked off the University of New England’s 2014 diversity lecture series with a talk on why “race” is a destructive concept.

The 2012 Anisfield-Wolf nonfiction award winner for “Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave and Exterminate Others” stated his mission at the top: “I wish to liberate you. I do not think I will succeed, but I hope I will raise questions about certain beliefs you take for granted.”

Smith presented his audience with a slide of four individuals with light skin and typical European facial features. He then asked the audience if they could determine which two were, in fact, African-American. It proved puzzling for those assembled. (See the slide here.)

“Virtually every genocide that I know enough about has been a racialized genocide,” Smith told his listeners on the Maine campus. “The notion of race gets us into a lot of trouble.”

Smith, who has taught philosophy at the university since 2000, is also the co-founder of The Human Nature Project, which explores evolutionary biology and human nature. He is the author of seven books, including Less Than Human, a centerpiece text in several college classes, including the Anisfield-Wolf course at Case Western Reserve University.

Watch his entire talk below on the “race delusion” and share your thoughts:

By Lisa Nielson, Anisfield-Wolf SAGES Fellow

Lisa Nielson is the Anisfield-Wolf SAGES Fellow at Case Western Reserve University. She has a PhD in historical musicology, with a specialization in Women’s Studes, and teaches seminars on the harem, slavery and courtesans.

I was introduced to “Less than Human” last fall when I had the pleasure of hearing David Livingstone Smith speak at the 2012 Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards ceremony and at Case Western Reserve University the next day. His presentation was riveting, and I felt myself vacillating between awe at the breadth of his work and shock at the horror of what humanity has done through dehumanization.

Judging from the taut silence as the awards audience of 800 heard Smith speak, they had a similar reaction. Listeners occasionally gasped as Smith told the story of Ota Benga, a Batwa (“pygmy”) tribesman, who was bought from a slave merchant in what was then called the Congo Free State and put on exhibit at the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904.

Eventually, Benga was put on display at the newly opened Bronx Zoo, sharing a cage with an orangutan. Black clergy protested, and, “buckling under the pressure of controversy, zoo authorities released Ota Benga from his cage, and allowed him to wander freely around the zoo, where jeering crowds pursued him,” Smith said.

The story ends with Benga succumbing to madness, and putting a bullet through his own heart.

In reflecting on this anecdote and the book, I was struck by Smith’s observation that for all that has been written about genocide, war, and dehumanization, little scholarship centers on why and how. Why have we not studied this process? Does our discomfort prevent us? Or are we afraid of what we might find?

Using an interdisciplinary approach, Smith not only goes into the philosophical and historical development of modes of dehumanization, but how religion, science and biology have been used to bolster both the practice and justification of demeaning others. By delving into how humans identify and react to difference, he also reflects on the cognitive and emotional processes we use.

Perhaps the most compelling evidence for me was his inclusion of research into human biology, cognitive science and the animal world. His synthesis of the biologic and psychological impulses behind our ability to dehumanize in comparison to similar species, such as chimpanzees, made a great deal of uncomfortable sense. He finds: 1) we are biologically wired to categorize strangers as “other”, 2) because of our propensity to order our world according to our perception of kinds and essences, there is a definable process we adhere to when categorizing who is “us” and “not us,” 3) as a result, we are all capable of extreme violence or cruelty given the right push, and 4) we are unique in the animal kingdom for so doing.

Smith doesn’t stop there. He confronts us with the reality that perpetrators of genocide are not outliers or “monsters” but often just like us. Drawing on Hannah Arendt’s theory of the “banality of evil,” he points out that we all have the capability to dehumanize, and argues that we must work to recognize and refute these impulses if we are to rise above them. Since these are complex social and psychological constructs, the same ability that allows us to dehumanize can also help us overcome our innate, and arguably submerged, hard-wired reactions to difference.

The evidence Smith uses to craft his theory shows that our propensity to dehumanization comes out of a complex of biology, social pressure, psychology around real and perceived danger, politics, and propaganda. Yet, our ability to reflect and make the better choice offers some hope for change. Such change, however, requires effort. As Smith notes in his conclusion, we have barely tried.

As the first Anisfield-Wolf SAGES Fellow, I have worked to incorporate explorations of race and diversity into my teaching. When I designed a class on world slavery, it allowed me to introduce books that have won the prize. This spring, I added Smith’s book to my reading list, and began the first week of class with his chapter on slavery, “The Rhetoric of Enmity.”

Student reaction has been profound. The students immediately took to his ideas and incorporated them into their essays and final projects. Some have offered insightful critiques and suggestions for expanding on his theory, while others have used his ideas as a basis from which to interrogate past and present constructions of race, class, sexuality and gender.

Though Smith doesn’t focus specifically on slave systems or gender in “Less than Human,” his outline of the process of dehumanization has changed the way I think about and teach slavery. Is slavery inherently a dehumanizing process, through the fact of being owned? Are there slave systems where this is not the case? How can dehumanization be applied to issues of gender and sexuality? And, in considering the continuation of dehumanization tactics today: What more can I do to help my students critically assess the social and cultural messages they receive?

If we accept that we are all prone to certain kinds of essentialist thinking, it is vital that we give students every tool to challenge their own assumptions, and to listen empathetically to others. This type of intellectual discipline takes a lot of effort, and we need people who can and are willing to do the work. My students at Case have that will and ability, and they inspire me to hope.

The 2012 election cycle was filled with a bombardment of political ads, 24-hour news cycles dissecting every possible angle, and an overwhelming sense of hype surrounding who will be our next batch of elected representatives. Some of our winners got in on the action and made a few comments about the election as well.

Junot Diaz, who has been writing consistently about the Latino effect in this year’s election, wrote a special message on his Facebook page. “Obama WINS!” he wrote shortly after the race had been called. “The Latino community came out BIG for Obama. Very proud of my community, very proud of all the new voters, the very proud of all the Obama supporters who put in the time and the hard work to make this happen.”

Never one to shy away from his passions, David Livingstone Smith took the opportunity to remind people of the atrocities happening in East Africa. “While we’re celebrating, they’re dying. How about urging our newly elected officials to take notice?”

Isabel Wilkerson, whose 2010 book, The Warmth of Other Suns, was selected as a top five book pick by President Obama, gave a brief history lessons for her fans on her Facebook page. “‘The right of citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.’ Those words, the 15th Amendment, were ratified in 1870. NINETY-FIVE years passed before it was acted upon. Poll taxes, literacy tests and lynchings barred black southerners from voting. It wasn’t until Aug. 6, 1965, when, after decades of protest and violence, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act ‘to enforce the fifteenth amendment to the Constitution,’ that everyone was actually permitted to vote.”

Whoever you supported and whatever your political leanings, we hope you took advantage of your right to vote and made a difference in this election cycle!

Filmmaker Al Sutton was inspired by our 2012 award winner David Livingstone Smith‘s 2007 book, The Most Dangerous Animal: Human Nature and the Origins of War.

“We have killed over 200 million people over the past century by war and genocide,” Sutton writes in the film’s description. “We must stop the killing to protect our loved ones, ourselves, our future.”

Watch the film here and let us know what you think!

We won’t spend too much time on an introduction today; let’s get right to the meaty stuff. Recently, our 2012 winners all had a chance to speak with Dred-Scott Keyes on the Public Radio Exchange to discuss their books and the deeper themes within. Take a listen to David W. Blight and Esi Edugyan in part one, and David Livingstone Smith and Arnold Rampersad in part two:

We are roughly a month away from the 2012 Anisfield-Wolf ceremony and is customary, we are alerting fans to several opportunities to meet our 2012 winners.

Cuyahoga County Public Library, Beachwood Branch (In the Meeting Room)

25501 Shaker Boulevard

Beachwood, Ohio 44122-2398

Corner of Richmond & Shaker Boulevard

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

7:00 PM – 8:30 PM

Registration is recommended. Click here to register.

Baker-Nord Center for the Humanities (Clark Hall Room 309)

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

4:30 PM – 5:30 PM

This event is free and open to the public.

Registration is recommended. Click here to register.

2012 nonfiction winner David Livingstone Smith, author of Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave and Exterminate Others, will be a on a panel at the G20 Summit in Mexico. He’s featured on a panel about provoking understanding, dealing with transforming communities and exploring new paradigms. In the video above, he explains why humans lie, and why it’s a part of human nature. He tells the audience, “The picture we have now is lying is pervasive…because it’s natural. It comes naturally to us. It’s not something our parents have to teach us.”

“This book is the first serious study of the phenomenon of dehumanization,” David Livingstone Smith says in this recent interview on his book, Less Than Human. “No one has really looked into what goes on when human beings think of other groups of human beings as sub-human creatures.”

Check out the full interview to see how dehumanization has contributed to global crises like the Holocaust and global wars. Visit his website at RealHumanNature.com.

“The 2012 Anisfield-Wolf winners reflect the complexity of the issues of race and cultural diversity in our world,” said Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute for African and African-American Research at Harvard University, who serves as jury chair. “These books and the people who created them help us gain a deeper understanding of the need to respect both the humanity and individuality of one other.”

Our 2012 winners are (click on any of the photos to read more on the authors):

Philosopher

Philosopher