“I’ll tell you what freedom is to me—no fear,” Nina Simone wistfully told an interviewer in 1968. “If I could have that half of my life…”

This search for freedom haunts each beat of “What Happened, Miss Simone,” the new Netflix-commissioned documentary on the award-winning singer, pianist and activist. The film, book-ended by Simone singing her classic “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free,” traces her journey from a piano prodigy in small town North Carolina to an international force of blues and soul.

“What Happened, Miss Simone” reaches viewers months before the highly controversial “Nina” biopic—in which Afro-Latina actress Zoe Saldana dons facial prosthetics to more closely resemble Simone. Simone’s only child, Broadway actress Lisa Simone Kelly, prefers the documentary: “[This film] reboots everything to what it’s supposed to be in terms of mom’s journey and mom’s life the way she deserves and the way she wants to be remembered in her own voice on her own terms.”

Born Eunice Waymon in 1933, the young girl’s early aptitude for music inspired a rare communal pride in her segregated town: both black and white residents contributed to a fund to send her to the Juilliard School in New York. When she applied to the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, the admissions office turned her down. “It took me six months to realize it was because I was black,” Simone said. (The institute would later award her an honorary degree two days before her death in 2003.)

Fresh out of money, the 19-year-old took the first job she could find—playing piano in an Atlantic City bar: “The owner came in the second night and told me if I wanted to keep the job, I had to sing. Ninety dollars was more money than I ever heard of in my life, so I sang.”

She changed her name to Nina Simone to avoid having her preacher mother discover she was playing secular music for a living. Yet it was the classical training that made her stand out. Soon she found herself performing at jazz festivals, drawing attention with her booming vocals.

“What I was interested in was conveying an emotional message, which means using everything you’ve got inside you, sometimes to barely make a note, or if you have to strain to sing, you sing,” she explained. “So sometimes I sound like gravel and sometimes I sound like coffee and cream.”

Her then-husband Andrew Stroud quit his job as a New York City police sergeant to oversee her career. Mutual friends described him as a man who could spook you with one word; their love affair quickly turned violent.

“Andrew protected me against everybody but himself,” she spat in one interview. “He wrapped himself around me like a snake.”

While Simone aspired to commercial success, the relentless pressure of being the breadwinner for an entire entourage— at one point she counted 19 people on her payroll—exhausted her: “Inside I’m screaming, ‘Someone help me’ but the sound isn’t audible – like screaming without a voice,” she wrote in her journal. “Nobody’s going to understand or care that I’m too tired. I’m very aware of that,” she later said.

Stroud recounted a story of Simone having a mental breakdown before a performance. “She had a can of shoe polish. She was putting it in her hair. She began talking gibberish and she was totally out of it, incoherent.” No one took her to get help; instead, Stroud took her arm and escorted her to the piano on stage. The show must go on.

Kelly, who also produced the film, uses her screen time to “explain” her mother, to smooth some of the controversial aspects of the entertainer’s life. For the most part, she is successful: “She was happiest doing music. I think that was her salvation. It was the one thing she didn’t have to think about.”

As her marriage imploded, Simone entered the burgeoning civil rights movement, flourishing in the company of contemporaries like James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry and Langston Hughes. “I could let myself be heard about what I’d been feeling all the time.” The 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four little girls enraged her. She wrote “Mississippi Goddam,” which soon became her best-known song and an anthem of the movement.

As Simone’s priorities shifted to what she called “civil rights music,” promoters shifted away and her career stalled. After stints in Barbados and Liberia, she settled in Europe to mount a comeback. Friends took in her disheveled appearance and odd behavior and took her to the doctor, where she was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, a disease many suspected she struggled with most of her life.

It’s never quite clear how close Simone would have considered some of the individuals tapped to interview; director Liz Gruber’s decision to gloss over their connection weakens the film. But the inclusion of Simone’s journal entries—she talks about contemplating suicide, of taking pills simply to function—gives an unvarnished insight into a woman of genius whose complexity makes her difficult to sum up, or pin down.

The second installment in March, Rep. John Lewis’ acclaimed graphic memoir trilogy on the civil rights movement, picks up where the first volume left off, but this book is more handbook than history lesson.

“I see some of the same manners, some of the same thinking, on the part of young people today that I witnessed as a student,” the Georgia Congressman, 74, told the New York Times. “The only thing that is so different is that I don’t think many of the young people have a deep understanding of the way of nonviolent direct action.”

March: Book Two, released in January, offers a robust crash course. This book centers on a young Lewis and his increasing responsibility within the movement from 1960 to 1963. The graphic memoir opens on young protesters staging a sit-in at a Nashville lunch counter. The peaceful protest soon turned ugly as the restaurant owner deployed a fumigating device to drive away the demonstrators. Lewis, by then seasoned, was still in disbelief: “Were we not human to him?”

Those sit-ins led to the Freedom Rides of 1961. In his letter to organizer Fred Shuttlesworth, Lewis was resolute in his desire to participate: “This is the most important decision in my life — to decide to give up all if necessary for the freedom ride, that justice and freedom might come to the deep south.”

The harrowing bus rides — orchestrated to test the new anti-segregation bus laws made possible by the Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia — unleashed angry mobs that bloodied and battered many of the riders. This led to conflict within the movement, with divisions growing between members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. (Lewis would later become chairman.)

The book culminates with the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where a 23-year-old Lewis spoke sixth. A sense of relief settles in for the reader, yet it doesn’t last long. The final pages are a sledgehammer to the gut. It is clear: there is much more work to do.

Interwoven with this narrative is the historic 2009 inauguration of Barack Obama, shown through Lewis’ eyes. The juxtaposition is stirring but somber.

Lewis’ goal is not simply to explain the methods of the movement, but also the soul. Book Two’s greatest strength is its focus on sacrifice — the graphic memoir centers on the physical, emotional and financial price paid by those at the forefront of the movement. Lewis praises his comrades repeatedly for their intellect and fortitude, allowing them to shine alongside King. (He is particularly fond of A. Phillip Randolph, noting, “If he had been born at another time, he could’ve been president.”)

Lewis’ senior aide Andrew Aydin is a co-writer, as he was for the first book. Both are illustrated by award-winning cartoonist Nate Powell, who does exceptionally detailed work here. Almost two years ago, March: Book One became required reading for first-year students at several major universities. Moreover, schools in more than 40 states are teaching March at the elementary, middle, and high school levels. USA Today and The Washington Post named it one of the top books of 2013.

At the debut of March, Lewis said, “I hope that this book will inspire another generation of people to get in the way, find a way to get into trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.”

The veteran Civil Rights leader, survivor of a concussion and beating from Alabama State Troopers on Bloody Sunday, asks in a new essay: “If Bloody Sunday took place in Ferguson today, would Americans be shocked enough to do anything about it?”

Lewis, winner of an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for his memoir “Walking With the Wind,” sees the recent police killings of unarmed black people as representing “a glimpse of a different America most Americans have found it inconvenient to confront.”

Writing in the Atlantic, Lewis’ words are tinged with weariness. In his essay, he draws on a 1967 speech by Martin Luther King Jr., in which King tells of the “other America,” one in which justice doesn’t come easy, if at all. Black Americans have been continually “swept up like rubbish by the hard, unforgiving hand of the law,” the Georgia Congressman writes.

“Ever since black men first came to these shores we have been targets of wanton aggression,” writes Lewis, 79. “We have been maimed, drugged, lynched, burned, jailed, enslaved, chained, disfigured, dismembered, drowned, shot, and killed. As a black man, I have to ask why. What is it that drives this carnage? Is it fear? Fear of what? Why is this nation still so willing to suspend the compassion it gives freely to others when the victims are men who are black or brown?”

Lewis is still marching toward a society where African-Americans might enjoy equal protection under the law: “One recent study reports that one black man is killed by police or vigilantes in our country every 28 hours, almost one a day. Doesn’t that bother you?”

Read the full post at The Atlantic.

Two elders of the American Civil Rights movement—Rev. Dr. Otis Moss Jr. and Rev. Dr. Joan Brown Campbell—went before a sold-out Cleveland crowd to consider “the unfinished business of race,” a topic heightened by the November police killing of Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old playing with a toy gun in a city park.

“Tamir Rice was our child, Cleveland’s child, God’s child,” Moss said at the City Club of Cleveland, “and every parent should feel the loss.”

Dr. Rhonda Williams, director of the Social Justice Institute at Case Western Reserve University, came directly to her point: “How do we dismantle white privilege?”

Moss, 79, who counseled U.S. presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, said the movement makes the most progress when its steps are deliberate. He listed, in order: research, education, mobilization, presentation of findings, negotiation, demonstration.

“The demonstration is not a means to itself but designed to bring about something higher,” said Moss, who served on the inner circle of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. “Whenever we followed the formula, we won. When we did not, we often lost.”

The former senior pastor of Cleveland’s landmark Olivet Institutional Baptist Church cautioned, “We cannot be filled with so much bitterness that our actions are taken as illogical.”

For her part, Campbell, 82, spoke directly to white privilege. She stressed that meaningful racial discussions must be honest, something she and Moss modeled at the City Club, drawing on long decades of friendship. She described professor John Hope Franklin at the Clinton White House calling on whites to be honest about the advantage they enjoy every morning, walking out of their homes free of suspicion simply because of their race.

“Otis Moss, you walk out knowing how the color of your skin makes a difference in how your day will go,” Campbell said, “even though you are Otis Moss in a town that loves you.”

Moss and Campbell told several stories apiece about victories and struggles waged a half century ago, often evoking King’s name. Throughout the room, there were tables of high school and college students, and a sense of generational change.

“Often we demean young people for going out without our approval, after we did the same thing in our time,” Moss said. Asked by a retired school teacher what to do about youth ignorance of history, Moss answered, “Adults don’t know their history either. People read history with their prejudices, not their minds.”

Jerome Mills, a senior at Shaw High School in East Cleveland, asked a question much on the audience’s mind: “How can we create change and protect ourselves in today’s world?” The African-American teen stood listening for an answer.

“Be the best you can be,” said Moss, who carries a copy of the Bible and the U.S. Constitution in his brief case wherever he goes. “Whatever you do, do it so well that no one dead, no one living and no one unborn could do it as well. When you become excellent, you become a leader. In your time and in your space, you can make a difference—at Shaw High School, in your community, in your living room and especially in the library.”

Moss held up Atlanta as an example of a city “willing to come to grips with race and racism there,” insisting, “justice is profitable; oppression is expensive,” an echo of the teaching of W.E.B. DuBois.

“In Ferguson, the dead person was put on trial and the living person, the police officer, was defended by the prosecutor,” Moss said, stressing that expecting victims of police violence to have led perfect lives is another form of racism.

Margaret Mitchell, who leads the YWCA Greater Cleveland, announced her organization’s arrangement of “It’s Time to Talk: Forums on Race” February 23 at the Renaissance Hotel in downtown Cleveland. She invited listeners to join, contribute, and perhaps become a racial justice facilitator for the day.

“It’s time for action, Cleveland,” Mitchell said, “on the unfinished business of race.”

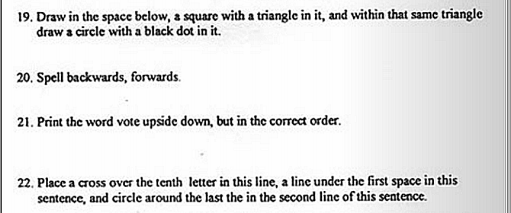

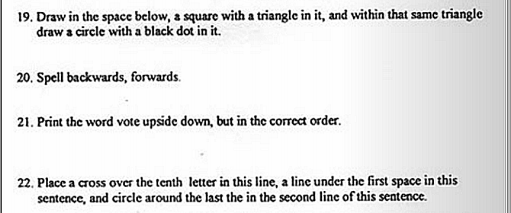

When the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act last month, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the watershed 1964 law had worked as intended: Racial discrimination had decreased and a record number of voters were now people of color. But how well do we remember the inequalities the law was protecting against?

A leader in the civil rights movement, Rep. John Lewis had a front-row seat to the tactics used to keep black people out of the voting booth. Physical intimidation, poll taxes, and literacy tests were all bent to the task. Segregationists designed literacy tests to be deliberately confusing. They imposed tight time constraints to increase errors. “Black people with Ph.D. and M.A. degrees were routinely told they did not read well enough to pass the test,” said Lewis, who won an Anisfield-Wolf award in 1998 for his memoir, Walking with the Wind.

The Civil Rights Movement Veterans has preserved copies of literacy tests administered in Louisiana and Alabama. A few sample questions below:

Lewis is organizing members of Congress to come up with new provisions for the Voting Rights Act. “We’ve come too far, made too much progress, to go back now,” he said in a recent MSNBC interview. “We’ve got work to do.”

View the full tests here.

“Some of you may be asking: ‘Hey, John Lewis, why are you trying to write a comic book?’” said the legendary civil rights leader, smiling at the incongruity of this development for an audience at Book Expo America, the annual publishing trade show in Manhattan.

John Lewis was 17 when he met Rosa Parks; 18 when he joined forces with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Five years later, he was one of the “big six,” an architect of the historic Civil Rights March on Washington in August 1963. Standing at the Lincoln memorial, Lewis spoke sixth and King spoke tenth, stamping the day with his immortal “I Have a Dream.” Of all those who addressed the throng a half century ago, Lewis is the only one left.

Now, at 73, he has become the first member of the U.S. Congress to craft a comic book. Called “March,” it will publish August 13, the first in a trilogy written with Lewis staff member Andrew Aydin and drawn by Nate Powell, the award-winning cartoonist.

The idea isn’t as whimsical as it sounds. Aydin, a comic book enthusiast from Atlanta, knew that in 1957, a 15-cent comic entitled “Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story” inspired the Greensboro Four. At least one read the comic and the four students from North Carolina A&T State University decided to sit down in protest at the segregated Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C.

Lewis himself led a group trying to integrate a Woolworth’s counter Feb. 27, 1960. They prayed and drew on the principles of non-violence. “People came up to us and spit on us and put cigarettes out in our hair,” he told listeners at the Book Expo. “I was so afraid, I felt liberated.” The episode led to jail, the first of Lewis’s more than 40 civil rights arrests.

He grew up on 110 acres in rural Alabama, the third child of sharecroppers who managed to buy the land for $300 in 1940. Young John liked to wear a tie and give sermons to the chickens. Local kids called him “preacher.” As a boy, he was instructed “not to get in the way” of whites, but he still applied for a library card in tiny Troy, Ala, where the librarian scolded him that they were only for whites.

On July 5, 1998, Lewis returned to Troy, for a book signing of his memoir, “Walking with the Wind,” which won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award that year. “At the end of the program, they gave me a library card,” he said. “It says something about how far we’ve come.”

Lewis said he initially resisted Aydin’s notion that he tell his story in a graphic format. The two were hammering up yard signs in southwest Atlanta during Lewis’ campaign for Georgia’s 5th District seat five years ago and chatting about how to teach the Civil Rights movement to 21st century youth.

“Finally, he turned around with that wonderful half-smile he can do and said, ‘OK, let’s do it,’” said Aydin. “‘Let’s do it, but only if you do it with me.’ ” Aydin called this a threshold event in his life.

Watch a short interview with John Lewis and Aydin at the 2013 Book Expo America

“When you grow up without a father you spend a long part of your adolescence looking for one,” said Aydin, who is now 29. He and artist Powell said “Walking with the Wind” became their Bible as they brought Lewis’ story into the present. The trio frame the trilogy around the 2009 inauguration of Barack Obama.

“We took the accuracy very, very seriously,” Aydin said. Powell, who grew up in Little Rock, Ark., and now lives in Bloomington, Ind., is drawing the second book now. He said he emails with Aydin almost daily, and when they are unclear, they consult Lewis.

“I feel the most important thing is to capture what is not explicit in the script,” Powell, 34, said. “I am looking for the emotional resonance – the doubt, fear, unity and togetherness that characterize the Civil Rights movement but don’t come with captions.”

He said he works hard researching the clothes, food, insects and plants that give his art verisimilitude. “It is very easy to get caught up in the drama of events,” Powell said, “but there is a lot of beauty in the South, in the red soil and the bricks, the kind of walking and talking people in the South do.”

Already, Powell has told one Civil Rights story in graphic form, “The Silence of Our Friends,” set in Houston in 1967 and written by Mark Long. It explores the tested friendship of two men across race.

The Congressman dedicates “March” to “the past and future children of the movement.” He told the publishing crowd in New York that another installment is overdue.

“I believe it is time to do a little more marching,” Lewis said. “I believe it is time for us to move our feet… I hope that this book will inspire another generation of people to get in the way, find a way to get into trouble, good trouble, necessary trouble.”

Most children learn about Rosa Parks’ contribution to the Civil Rights Movement thusly: She boarded a bus, refused to move to the back of the bus when a white passenger got on board, and was promptly arrested, kicking off the Montgomery bus boycott. Lasting roughly 13 months, the Montgomery bus boycott lead to an official Supreme Court ruling declaring segregation on public transportation unconstitutional.

While that did indeed happen, what is often overlooked is Rosa Parks’ earlier involvement with the civil rights movement. She was a member of the Montgomery NAACP chapter and even served as secretary for NAACP President E.D. Nixon. In honor of what would have been her 100th birthday this year, the Huffington Post recently highlighted some lesser known facts about Rosa Parks, including the fact that she had been thrown off the bus 10 years earlier by the same driver:

She had avoided that driver’s bus for twelve years because she knew well the risks of angering drivers, all of whom were white and carried guns. Her own mother had been threatened with physical violence by a bus driver, in front of Parks who was a child at the time. Parks’ neighbor had been killed for his bus stand, and teenage protester Claudette Colvin, among others, had recently been badly manhandled by the police.

Read the rest of the facts at the link and let us know – did you know any of this about Rosa Parks?