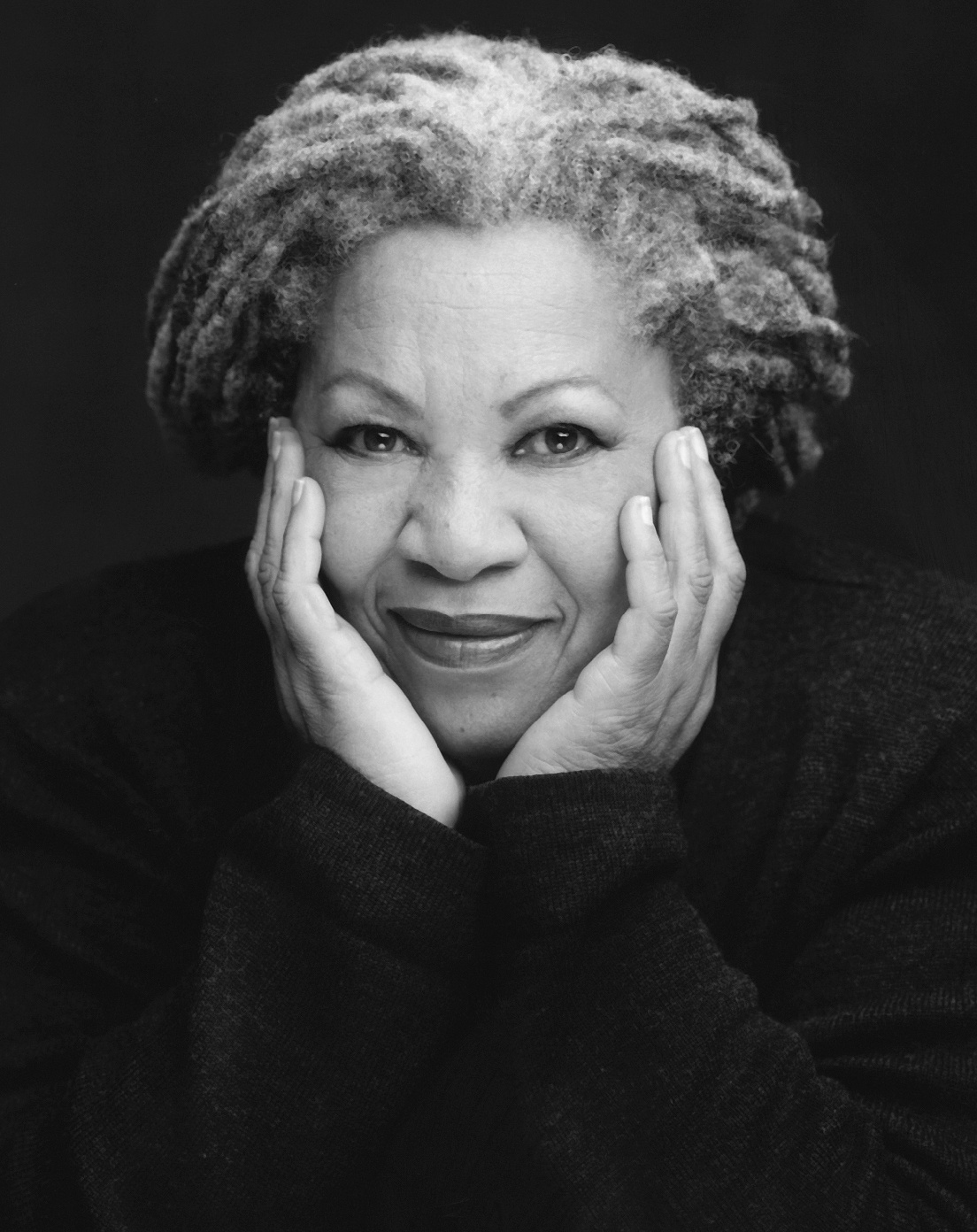

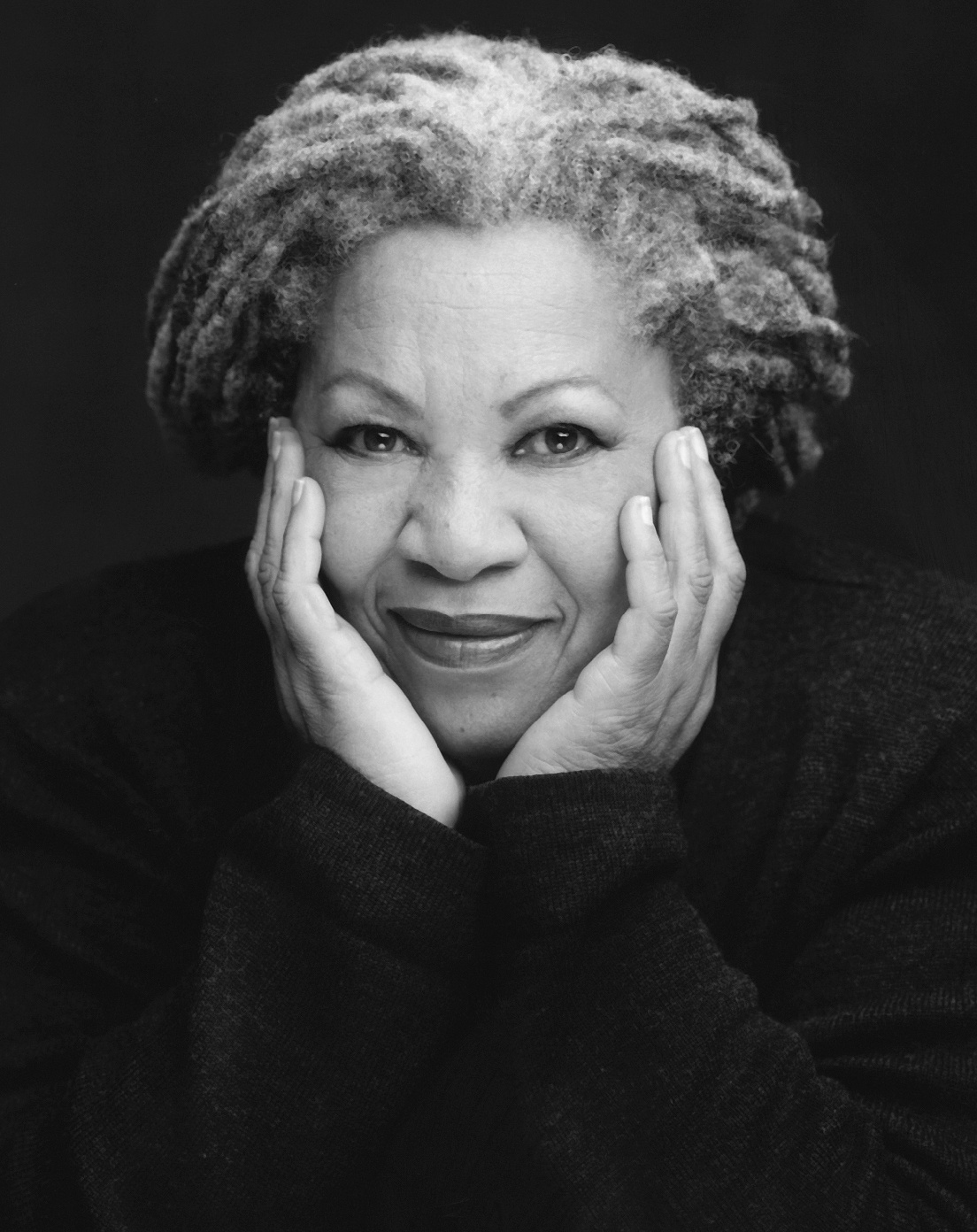

Thinking about gaps in our communal memory has long occupied Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison. In a 1989 interview, she said:

“There is no place you or I can go, to think about or not think about, to summon the presences of, or recollect the absences of slaves . . . There is no suitable memorial, or plaque, or wreath, or wall, or park, or skyscraper lobby. There’s no 300-foot tower, there’s no small bench by the road. There is not even a tree scored, an initial that I can visit or you can visit in Charleston or Savannah or New York or Providence or better still on the banks of the Mississippi. And because such a place doesn’t exist . . . the book had to.”

The book is her novel Beloved, now firmly in the American canon and winner of a 1988 Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. Morrison’s remarks galvanized a clutch of scholars, who organized the “Bench by the Road Project” in 2006 on the novelist’s 75th birthday. The Toni Morrison Society installed the first bench two years later on South Carolina’s Sullivan’s Island, gateway of 40 percent of the Africans who came to North America.

Professor Marilyn S. Mobley witnessed that quiet, first monument set upright on the island at the entrance to Charleston Harbor. She attended the second bench placement near Oberlin College, saw another installed in Paris, France and yet another on the campus of George Washington University in Washington, D.C. Each spot is a link to the African-American resistance history that Morrison evokes.

The 19th bench, dedicated this April in Cleveland, sits on a green swell of lawn in University Circle, identical in its simple design to the benches installed before it: black ribbed steel, a length of four or six feet, with a descriptive plaque mounted in a cement foundation next to it. On a recent spring morning, sparrows and squirrels hopped and scurried around it.

Mobley, vice president of inclusion, diversity and equal opportunity at Case Western Reserve University, said she spent two years working toward putting a bench in the neighborhood adjacent to campus, a community once active on the Underground Railroad.

“It was worth my time and trouble because I believe in the concept of the need to remember — remember and celebrate,” she said. “I want to remember this history, which is part of our identity as Americans: there was a group of people who made this difficult journey to freedom. We were more than our suffering, our indignity.”

Mobley collaborated with Joan Southgate, the legendary retired social worker, who, at the age of 73 in 2002, began walking from Ripley, OH to St. Catharines, Ontario, the terminus of Harriet Tubman’s Underground Railroad. She completed the 519 miles and walked 250 more back to Cleveland.

“To tell you the truth, I didn’t know much about the Bench by the Road until Marilyn brought the idea to me,” Southgate said. “It couldn’t have been more perfect. It’s what my walk was all about.”

Southgate expressed her deep pleasure with the placement of the bench on the lawn of the Cozad-Bates House, 11508 Mayfield Rd. It is the only pre-Civil War building left standing in this Cleveland neighborhood. Southgate is working to see that the structure, owned by University Circle Inc., will eventually reopen as a small abolitionist museum combined with a guesthouse for transplant patients.

“This bench is placed in recognition of the heroic freedom seekers who made the arduous journey to freedom along the Underground Railroad, aided in part by Cleveland’s African-American and White anti-slavery community,” reads the permanent proclamation. “Horatio Cyrus Ford and Samuel Cozad III, successful businessmen and property owners in the area now known as University Circle and African-American businessman and civil rights activist, John Malvin, were exemplars of Cleveland’s participation in the resistance to slavery and in the struggle for social justice. This bench is a memorial to the freedom seekers who passed through Cleveland and to those Cleveland residents who assisted them on their journey.”

The Toni Morrison Society states that “the goal of the Bench by the Road Project is to create an outdoor museum that will mark important locations in African American history both in the United States and abroad.” Its president, Carolyn Denard, flew from Atlanta to Cleveland to see the 19th bench unveiled.

Raymond Bobgan, executive director of Cleveland Public Theatre, said he would not have joined in the bench project without the blessing of Southgate. “We need to continue to acknowledge what we aren’t proud of in our history,” he said. “People sometimes say, ‘My family didn’t own slaves’ but the same people are happy to claim, say, the founding fathers. Well, both are our history, and both have repercussions in our lives.”

The 20th bench will be installed July 26 in Harlem, New York at the Schomburg Library in recognition of the institution’s century-long commitment to preserving, archiving and telling African-Americans stories. Papers from many winners of the Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards can be found on its premises, and embedded in the terrazzo tile of the lobby is a design honoring Langston Hughes’ seminal poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

At 84, Toni Morrison is full of reflection on her successes and incidents where she might request a do-over.

“It’s not profound regret,” she told NPR’s Terry Gross. “It’s just a wiping up of tiny little messes that you didn’t recognize as mess when they were going on.”

Morrison’s press tour for her eleventh novel,

God Help the Child, has been full of little fascinating admissions like this. (My favorite parts of the recent lengthy

New York Times profile are the quick revelations that Morrison has never once worn jeans and that she considers sleeping on ironed sheets one of life’s greatest luxuries.)

Her vulnerability is heightened during the NPR interview as she riffs on the pains and shifts that accompany older adulthood. As she has aged, her circle has become smaller; as a result, “there is this boredom or the absence of something to do.”

But the conversations all lead back to her novel, a haunting tale of childhood traumas sans redress. Bride, the main character in

God Help the Child, is a dark-skinned cosmetics executive struggling with the weight of rejection that has plagued her entire life. In her review for Newsday, Anisfield-Wolf manager

Karen Long calls the novel “hypnotic” and praises Morrison for her vivid language and pacing: “Morrison has a Shakespearean sense of tragedy, and that gift imbues “

God Help the Child.”

Anisfield-Wolf winner Toni Morrison found herself on stage at the Hay Festival in Wales May 28, the same day her friend Maya Angelou died in North Carolina at the age of 86. The obvious question—”Do you have any words to say about her life and legacy?”—was coming.

“She launched African-American women writing in the United States,” Morrison said, choosing her words carefully. “She was generous to a fault. She had 19 talents…used 10. She was a real original. There’s no duplicate.”

The friendship between Morrison and Angelou spanned more than 40 years. In 1973, Angelou wrote to Morrison after she finished reading Sula, telling her, “This is one of the most important books I’ve ever read.” Their friendship deepened as they continued to cross paths and support one another’s work over the decades. When Morrison won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1993, Angelou threw a party at her Winston-Salem home.

In 2012, Angelou traveled to Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University to toast Morrison’s contributions to literature. Poet Nikki Giovanni organized “Sheer Good Fortune,” a two-day celebration on the Blacksburg campus where she has taught since 1987. The guest list was historic, with Rita Dove, Edwidge Danticat, Sonia Sanchez and Angela Davis in attendance.

The writers assembled at Giovanni’s request, as a show of solidarity after the quick death of Morrison’s son Slade from pancreatic cancer in 2010. The gathering took its name from the dedication for Morrison’s 1973 novel, Sula :“It is sheer good fortune to miss somebody long before they leave you.”

Former poet laureate Rita Dove read from Song of Solomon. Poet Toi Derricotte selected a portion of Sula. Members of the Toni Morrison Society, now relocated to Oberlin, Ohio, performed a stirring passage from Beloved.

On stage, Maya Angelou smiled at the crowd and praised her friend for liberating her as a younger woman. “That is what this woman has done through 10 books: loving, respecting, and appreciating the African-American woman and all the things she goes through.”

Later, Morrison said, “This is as good as it gets.”

She gave credit to Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings for helping her discover the meaning in her work. “I had not seen that kind of contemporary clarity, honesty…sentences that were more than what happened, but how….I took sustenance from that. The door was open, so black women writers stepped through.”

Sheer Good Fortune – A Documentary from virginiatech on Vimeo.

Toni Morrison doesn’t hold her tongue on anything she deems important for the masses to know. At 82, she has earned that right.

In speaking with freshman cadets at the United States Military Academy, Morrison expressed her views on the war in Iraq and shared her inspiration for her latest book, “Home.” The novel, about a Korean war veteran named Frank Money, who is struggling with PTSD and the segregated south, is part of the English curriculum at West Point. Lt. Col. Scott Chancellor, director of the freshman English program, selected the book for their classes thanks to its relevant messages to troops today, particularly as it touched on race and trauma.

Col. Scott Krawczyk, the head of the academy’s English and philosophy programs, tied the book’s themes into the larger picture of the academy’s training:

“At West Point we ensure that cadets are made to struggle with moral ambiguity, so that when they confront tangled scenarios, they will be able to do that well. Morrison gives us just enough psychological complication of Frank Money to open up an understanding of how desperately malignant the realm of war can be.”

During the conversation, Morrison was vocal about her disdain for the war in Iraq (“I dare you to tell me a sane reason we went to Iraq”) and expressed concern about the number of veteran suicides (a recent report shows the suicide rate for veterans has risen 22% in the past 14 years).

For more on the speech, read the full article here.

Watch below as Morrison talks about “Home” and her intention to explore the themes of masculinity, war, and race.

We were thrilled to receive an invitation to participate in Toni Morrison’s first live digital book signing, courtesy of Google Play. We weren’t sure what to expect from the format—how would the digital signing of books work? How long would she speak? Would technical difficulties get in the way?

We were pleasantly surprised at how well the event went. Toni Morrison broadcast live from Google’s New York offices and the event was streamed live over several websites. Readers were encouraged to submit questions beforehand and a lucky few were selected to speak with Ms. Morrison herself. After the event, readers would be able to download signed digital copies from the Google Play store.

Casual, comfortable and inviting, the digital book signing was billed as a first-of-its-kind event, one we hope more authors consider when trying to determine how to best connect with readers. Ms. Morrison answered questions about the best advice she’s ever received, what advice she’d give to struggling writers, and what books, if given the chance, she might want to go back and change.

Editor Kelsey McKinney summed it up best in her review of the event (she was one of the lucky ones chosen to ask a question):

…it brought something to the reading community that has been missing: live interviews with the best minds of our time that anyone can watch…A big thank you to Google Play, and Toni Morrison for transforming a normal Wednesday afternoon into something I won’t forget.

We agree wholeheartedly.

Toni Morrison’s Pulitzer-prize winning novel, Beloved, took home the Anisfield-Wolf award for fiction in 1988. In it, a slave, unwilling to see her children grow up and live the same fate as their mother, killed one of her children rather than see them in bondage. Eighteen years later, the mother is visited by a young woman who she believes is the slain infant, returned.

However lauded the work may be, not everyone is a fan. Most recently, a Fairfax County parent has petitioned to ban the book based on the book’s content, which she says gave her son nightmares after he read it for his senior-level English class. “I’m not some crazy book burner,” Laura Murphy said. “I have great respect and admiration for our Fairfax County educators. The school system is second to none. But I disagree with the administration at a policy level.”

Of course, Ms. Murphy’s request is nothing new for the novel. According to the American Library Association, Beloved ranks 26th out of the most frequently banned books of the past 10 years. Its content (particularly the infanticide) has certainly disturbed many readers, but it is still lauded for its examination of the African American experience throughout the course of history—both good and bad.

In a 1987 interview with the New York Times, Toni Morrison talked about her inspiration for the book:

”I was amazed by this story I came across about a woman called Margaret Garner who had escaped from Kentucky, I think, into Cincinnati with four children. And she was a kind of cause celebre among abolitionists in 1855 or ’56 because she tried to kill the children when she was caught. She killed one of them, just as in the novel. I found an article in a magazine of the period, and there was this young woman in her 20’s, being interviewed – oh, a lot of people interviewed her, mostly preachers and journalists, and she was very calm, she was very serene. They kept remarking on the fact that she was not frothing at the mouth, she was not a madwoman, and she kept saying, ‘No, they’re not going to live like that. They will not live the way I have lived.'”

Morrison argued that her novel was not about slavery but a broader look at passion, self-sabotage, and the will of a people told they are less than human.

While Ms. Murphy may not succeed, her concerns about what is appropriate for children and young adults are very valid. Have you ever read a book you felt you were too young for, or have your children come home with a book you felt was above their maturity level?

In honor of Ms. Morrison’s 82nd birthday, we’re looking back at our archives for some of our favorite moments from the esteemed author over the past few years. Take a walk down memory lane with us:

“Beloved” is named one of the “88 Books That Shaped America” by the Library of Congress:

Toni Morrison won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her post-Civil War novel based on the true story of an escaped slave and the tragic consequences when a posse comes to reclaim her. The author won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1993, and in 2006 The New York Times named “Beloved” “the best work of American fiction of the past 25 years.”

She wins the 2012 Presidential Medal of Freedom:

In his personal remarks during the ceremony, President Obama said of Morrison’s work, “I remember reading Song of Solomon when I was a kid. Not just trying to figure out how to write, but also how to be. And how to think.”

“Home,” her 10th novel, hits newsstands in 2012:

The Washington Post wrote that in her latest novel, Morrison “has never been more concise, and that restraint demonstrates the full use of her power.” Read more reviews here.

Her legacy moves closer to home

Last year, the Toni Morrison Society, a group of scholars, moved its headquarters from Atlanta to Oberlin, Ohio. Morrison grew up in nearby Lorain, where she still has family. Founded in 1993, the society supports the teaching, reading, and critical examination of Toni Morrison’s works.

On December 6, Toni Morrison will deliver the Ingersoll Lecture on Immortality at 5 pm in Sanders Theatre on the Harvard campus. Throughout the fall semester, Harvard Divinity School has hosted a working group on the religious dimensions of Morrison’s writings. Watch the video here.

If you’re interested in attending, tickets may be requested from the Harvard Box Office. Limit of 2 tickets per person. Tickets are available by phone and internet for a fee, or in person at the Holyoke Center Box Office. Call 617.496.2222 or reserve online at www.boxoffice.harvard.edu. Limited availability. Tickets are valid until 5:00 pm on the day of the event.

The event will be live-streamed via a link on the Harvard Divinity School home page beginning at 5:15 pm.

If you are in the area and able to attend, let us know your thoughts on Morrison’s lecture!

More than 35 years after being published, Toni Morrison’s “Song of Solomon” is behind a bit of controversy in the Frederick, Maryland school district.

From the Frederick News Post:

School board member April Miller would not vote to make “Song of Solomon” available in Frederick County high schools.

The novel by Toni Morrison, which details the life of an African-American male living in Michigan from the 1930s through 1960s, includes graphic sexual and violent content.

“It’s definitely not something I want my 14-year-old reading,” she said Thursday in a phone interview.

Miller’s daughter will be a high school freshman next year.

“Song of Solomon” was set to be approved Wednesday in the Frederick County Board of Education’s consent agenda, which requires only a yes or no vote with no discussion, before Miller asked that the item be pulled for discussion.

Miller is asking that the lists of books to be approved be given to board members in advance so they have time to read the books and make a more informed decision about which books should be available in the curriculum. Other board members disagree, saying they are not curriculum experts and should trust the school’s discretion.

Sound off in the comments—where do you stand?

We found this piece of art by local artist John Sokol fascinating. In it, he uses words to fill in the visage of Ms. Toni Morrison (perhaps words from her own works?).

Visit the link to see more of his “word portraits,” including those of James Joyce, Dante, and more.

Anytime – and we do mean anytime – there is a new Toni Morrison interview or book or appearance, we pay attention. Not just because she is a 1988 Anisfield-Wolf winner, but because she is a literary treasure. She is 81 now, having spent roughly half her life as an author of note and with is comes the freedom and space to say exactly how she feels about any given topic.

She recently sat with a writer from the Daily Telegraph for an in-depth interview in advance of her latest work, a play, which opened in London this month. In it, she collaborates with director Peter Sellars and Rokia Traore to retell the story of “Othello,” one of Shakespeare’s most-known works, this time giving more depth to Desdemona, Othello’s lover and wife.

In the incredibly rich interview, Morrison talks candidly about a variety of subjects. We pulled some of the best quotes:

On her son’s death:

“People speak to me about my son – ‘I’m so sorry for you’ – but no one says, ‘I loved him so much.’ I was busy in grief, which I don’t expect to stop. Suddenly realising that the last thing my son would want was for me to be very self-involved and narcissistic and self-stroking. It stopped me from writing. Which doesn’t mean you stop feeling the absence. It was being willing to think about it in a way that was not self-serving.”

On why she wanted to take on Shakespeare:

“Black classically trained actors love the role because it’s one of the few times that they are the stars. So the same old version gets repeated. And I didn’t find justification for that conventional view in Othello. I was interested in a different rendering of her.”

On where she considers home:

“I live in places that I love. And I’d hate to lose them. The house on the river I’ve been in since the Seventies. But home is an idea rather than a place. It’s where you feel safe. Where you’re among people who are kind to you – they’re not after you; they don’t have to like you – but they’ll not hurt you. And if you’re in trouble they’ll help you…”

The whole interview is worth a read – we think you’ll find it one of the highlights of your day.

No, it’s not a “best books of all-time” list, but the list assembled by the Library of Congress, to celebrate the works that most define our nation’s history, is pretty close. There’s some stand-outs, like Thomas Paine’s Common Sense and Dr. Seuss’ The Cat in the Hat. But the list particularly caught our eye because there are several Anisfield-Wolf winners on the list—and we’re thrilled. Check out who made the cut. Descriptions are pulled from the Library of Congress website:

Langston Hughes, “The Weary Blues” (1925)

Langston Hughes was one of the greatest poets of the Harlem Renaissance, a literary and intellectual flowering that fostered a new black cultural identity in the 1920s and 1930s. His poem “The Weary Blues,” also the title of this poetry collection, won first prize in a contest held by Opportunity magazine. After the awards ceremony, the writer and photographer Carl Van Vechten approached Hughes about putting together a book of verse and got him a contract with his own publisher, Alfred A. Knopf. Van Vechten contributed an essay, “Introducing Langston Hughes,” to the volume. The book laid the foundation for Hughes’s literary career, and several poems remain popular with his admirers.

Zora Neale Hurston, “Their Eyes Were Watching God” (1937)

Although it was published in 1937, it was not until the 1970s that “Their Eyes Were Watching God” became regarded as a masterwork. It had initially been rejected by African American critics as facile and simplistic, in part because its characters spoke in dialect. Alice Walker’s 1975 Ms. magazine essay, “Looking for Zora,” led to a critical reevaluation of the book, which is now considered to have paved the way for younger black writers such as Alice Walker and Toni Morrison.

Gwendolyn Brooks, “A Street in Bronzeville” (1945)

“A Street in Bronzeville” was Brooks’s first book of poetry. It details, in stark terms, the oppression of blacks in a Chicago neighborhood. Critics hailed the book, and in 1950 Brooks became the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. She was also appointed as U.S. Poet Laureate by the Librarian of Congress in 1985.

Ralph Ellison, “Invisible Man” (1952)

Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” is told by an unnamed narrator who views himself as someone many in society do not see, much less pay attention to. Ellison addresses what it means to be an African-American in a world hostile to the rights of a minority, on the cusp of the emerging civil rights movement that was to change society irrevocably.

Malcolm X and Alex Haley, “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (1965)

When “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” (born Malcolm Little) was published, The New York Times called it a “brilliant, painful, important book,” and it has become a classic American autobiography. Written in collaboration with Alex Haley (author of “Roots”), the book expressed for many African-Americans what the mainstream civil rights movement did not: their anger and frustration with the intractability of racial injustice.

Toni Morrison, “Beloved” (1987)

Toni Morrison won the 1988 Pulitzer Prize for fiction for her post-Civil War novel based on the true story of an escaped slave and the tragic consequences when a posse comes to reclaim her. The author won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1993, and in 2006 The New York Times named “Beloved” “the best work of American fiction of the past 25 years.”

Check out the full list here.

We’ve been talking about Toni Morrison a lot lately, but we think it’s difficult to provide too much information on one of our greatest living writers. Bookriot named May 8 “Toni Morrison Day,” in honor of the release of her newest book, but we’re going to extend it one day and share one more video of the great Ms. Morrison. In it, she discusses the early part of her career and what she thought of the “Black is Beautiful” movement.

It’s not very likely to hear us expressing doubt about Ms. Toni Morrison‘s literary abilities. If anything, our appreciation for her craft only grows larger with the release of each new work. Her latest novel, Home, explores the homecoming of Frank Money, a Korean War vet who signed up for the service to get away from his hometown, only to return weary and disturbed and not sure of how welcome he will be. The reviews are in—is this still the Toni Morrison we all know and love?

Toni Morrison’s new novel “Home” is a slim volume. That alone excuses it from providing the sweeping exhilaration of “Beloved” or “Song of Solomon.” But “Home” is also a lesser novel — still powerful, still moving, but not her best work.

In addition to her reputation for gorgeous sentences, Morrison is known for a certain brutality in her plotting, and this wrenching novel is no exception. But “Home” also brims with affection and optimism. The gains here are hard won, but honestly earned, and sweet as love.

Ultimately, the impression with which “Home” leaves us is of a novel that, like the town it encircles, is “much less than enough.” Or maybe it’s that the book seems tired, as if it were something we’ve read before. Either way, it leaves us wanting, without the discovery, the recognition of how stories can enlarge us, that defines Morrison’s most vivid work.

At just 145 pages, this little book about a Korean War vet doesn’t boast the Gothic swell of her masterpiece, “Beloved” (1987), or the luxurious surrealism of her most recent novel, “A Mercy” (2008). But the diminutive size and straightforward style of “Home” are deceptive. This scarily quiet tale packs all the thundering themes Morrison has explored before. She’s never been more concise, though, and that restraint demonstrates the full range of her power.

Will you be reading her latest book?

In anticipation for Toni Morrison’s latest novel, Home, following the story of a Korean War veteran and his return to America in the 1950s, New York magazine wrote one of the best pieces on Toni Morrison that we’ve ever read. In it, writer Boris Kachka examine her feelings on her pen name (Surprise! She hates it), whether she believes her writing is as good as other people say it is (she does) and much, much more. We’ve lifted some of the best excerpts and encourage you to read the full piece. It’s extraordinary:

On whether she deserves to be listed among the all-time greats,

regardless of skin color:

But two decades after she won her Nobel, Toni Morrison’s place in the pantheon is hardly assured. A writer of smaller ambitions would live on contentedly in this plush purgatory, but Morrison writes—more and more consciously, it seems—for posterity. Having once spearheaded the elevation of black women in culture—Maya Angelou, Alice Walker, Oprah—she now finds herself struggling to cut them loose, to admit at long last what she’s always believed: that she’s not only the first, but the best. That she belongs as much with Faulkner and Joyce and Roth as she does with that illustrious sisterhood. That she will pass the test that begins only after Chloe Wofford is gone, and Toni Morrison is all that’s left.

On how she managed to develop such a strong command of literature

and storytelling:

At night her parents told R-rated ghost stories, like one about a murdered wife who returned home holding her own severed head. The following evening, the kids had to retell the tales with variations: Maybe it was snowing, or there was blood dripping from the head. “This was all language,” she says now. There were also fifteen-minute plays on the radio, which “influenced me as much if not more,” she remembers. “If they said ‘green,’ you had to figure out in your head what shade that was. And you only heard voices. So everything else you had to build, imagine. Everything.”

On what writing represents to her:

“All of my life is doing something for somebody else,” she says—though her children are long grown and she’s been divorced for almost 50 years. “Whether I’m being a good daughter, a good mother, a good wife, a good lover, a good teacher—and that’s all that. The only thing I do for me is writing. That’s really the real free place where I don’t have to answer.”

Read the rest of the article here and tell us – did you come away with a different view of Ms. Morrison? What book of hers is your favorite?

Junot Diaz’s short story collection This Is How You Lose Her will be published in September. It’s Diaz’s first book since his 2007 debut novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which, in addition to the 2008 Anisfield-Wolf award for fiction, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and National Book Critics Circle Award. {New York Times}

It hasn’t been officially confirmed but the rumor mill is buzzing that Zadie Smith’s latest book will be released in September. No doubt fans of White Teeth and On Beauty are waiting anxiously. {Sarah Weinman}

Toni Morrison’s 10th novel, Home, will be released May 8. It follows an African American Korean war veteran who returns to his Georgia community a changed man. {L.A. Times}

Oberlin College will host 1988 Anisfield-Wolf award winner Toni Morrison in an intimate event on Wednesday, March 14 at 7:30. The Nobel-prize winning author will read from her upcoming novel, Home, as well as participate in a question-and-answer session. The public can request tickets by sending a self-addressed stamped envelope along with your request to:

Central Ticket Service

Hall Auditorium

67 N. Main St.

Oberlin, OH 44074

If you have the opportunity to go, we highly recommend you take the time to see Ms. Morrison in person. In the meantime, check out this reading Toni Morrison delivered in late 2011, at George Washington University:

Because it is more appealing to hear from the authors themselves, we’ve rounded up some of the best quotes we’ve heard this year (even if they’re a bit older) from some of our distinguished Anisfield-Wolf Award winners. Enjoy!

“I want you to show them the difference between what they think you are and what you can be.”

— Ernest J. Gaines, A Lesson Before Dying

”At some point in life the world’s beauty becomes enough. You don’t need to photograph, paint or even remember it. It is enough.”

— Toni Morrison

”Art, after all, is – at its best – a lie that tells us the truth.”

— Nam Le

”Poetry is what you find / in the dirt in the corner, / overhear on the bus, God / in the details, the only way / to get from here to there.”

— Elizabeth Alexander, Ars Poetica #100: I Believe

“One of the things I love about writing novels is that you realize that you’re not all that interested in the bottom. You’re more interested in things that are bottomless. You become fascinated by the questions, and the answers to those questions are secondary, if they become important at all.”

— Nicole Krauss

“An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he might choose.”

— Langston Hughes