By Gabrielle M.W. Bychowski

In 1959, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in nonfiction for his memoir, Stride Toward Freedom. The book detailed King’s organizing efforts with the Bus Boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, as well as how he developed his philosophy of nonviolent resistance. This is a book I have had the pleasure of teaching multiple times.

A few years later, in 1966, Malcom X won the same prize for his autobiography, ghost-written by Alex Haley. This text follows Malcolm through his upbringing, his years in prison, and his conversion to Islam. Like King’s book, this work contextualizes the philosophy of activism that Malcom X championed. I have also treasured teaching this autobiography to students with mixed preconceptions. Both of these books have proven indispensable in humanizing two well-known figures in the civil rights movement.

Yet in part through these narratives, I am conscious of the many women in the movement who have largely gone unnoticed within the classroom. Examining the list of other Anisfield-Wolf Book award winners from the late 1950s and 1960s, I find few representatives of women’s contributions in the fight for social justice.

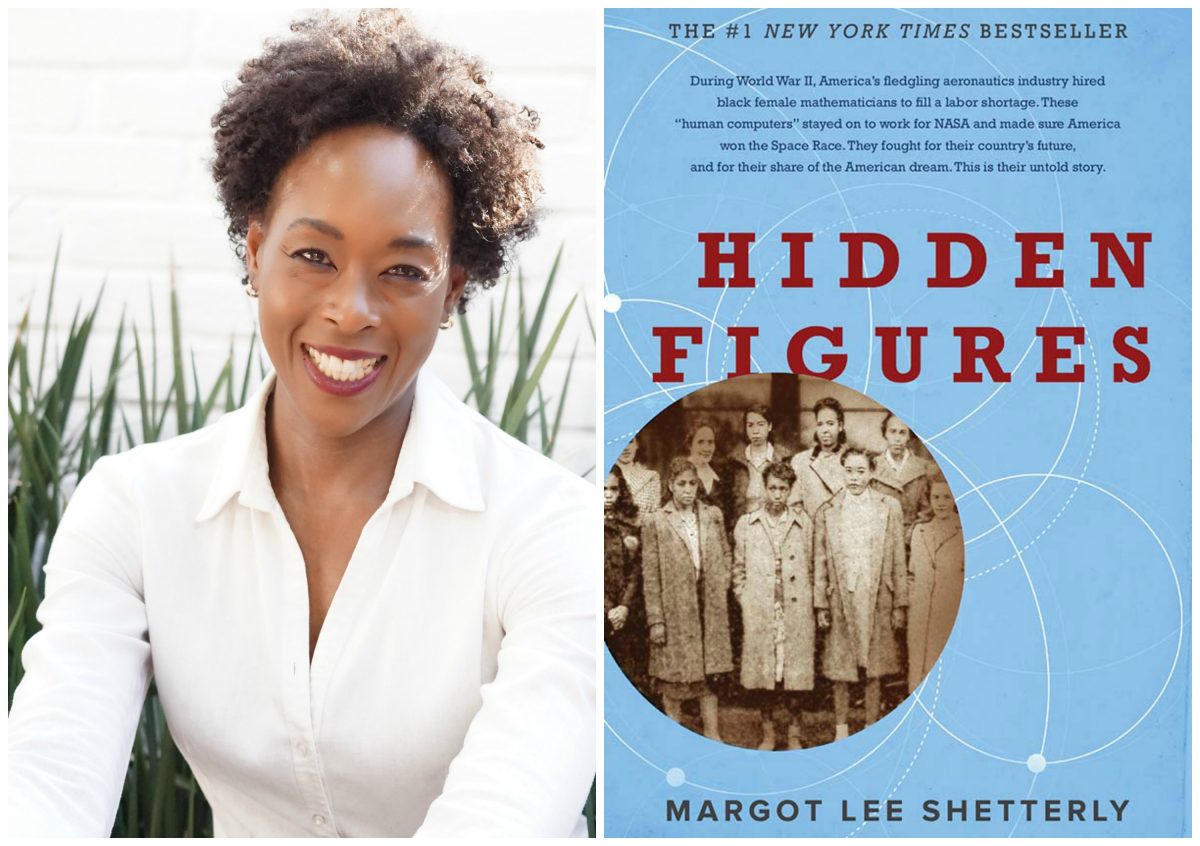

Nearly 60 years after Dr. King’s win, Margot Lee Shetterly’s Hidden Figures won the Anisfield-Wolf prize for nonfiction and illustrated the need for a seminar on the women of the civil rights movement. Centered around NASA’s women “calculators” during the Space Race, Shetterly’s book provides specifics about the role Black women played in not only getting men into orbit but also in desegregating areas of the country otherwise resistant to racial progress.

The name “Hidden Figures” engages in word play, signifying both the numerical figures computed by the women of NASA and the women as historical figures in their own right. Dorothy Vaughan (among others) serves as a leading figure in the history of Black women committed to the space race. She emerged shortly after NASA’s call for more women of color in 1943. Her struggles and rise through the ranks, however limited it was by the continuing misogynoir, offers teachers a useful trajectory to follow with students. She also became one of the three women featured within the 2016 film adaptation of Hidden Figures.

Langley functions as another site for discussion. Shetterly effectively contextualizes Dorothy and the other computers by establishing them in relationship both to the increasingly integrated NASA campus and the surrounding area of Virginia that remained mostly segregated. Emphasis can be placed on the psychological gymnastics of working together, even at a distance, with White scientists and mathematicians, then coming home to a community that still experienced a sharp division of space. This life/work contradiction became harder and harder to maintain, especially as new money and ideas trickled out into the surrounding neighborhoods, leading to the erosion of economics and intuitional walls. Teachers can connect how the military has facilitated (often against great internal and external resistance) social progress and mobility for diverse marginalized peoples, including women, the Black community, immigrants, and LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Hidden Figures can also operate as a quilting point for other texts and topics. Covering a range of years from the 1940’s to the 1980’s, the book comfortably spans decades in which various women contributed in various ways towards racial and gender equity. Chapters in the book can be divided throughout a semester, starting with Dorothy Vaughan early on and concluding with Mary Jackson. In between other “hidden” figures in history can be incorporated, flowing out from Shetterly’s work and then back into it.

Angela Davis jumps out as one such figure that might be highlighted. Synonymous in her own way with the civil rights movement, Davis nonetheless did not publish until the 1970s and never received an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. If an instructor takes a biographical approach, Davis’s 1974 autobiography could highlight her education, scholarship, and career with the Black Panthers. Other events like her arrest, travels abroad, and later life politics could also augment discussion of her life story. Alternatively, students might resonate with Davis’s academic and activist writings, perhaps comparing and contrasting Freedom is a Constant Struggle (2016) with Stride Toward Freedom.

Another companion text that I have taught alongside Hidden Figures is Lighting the Fires of Freedom: African American Women in the Civil Rights Movement. In a series of small vignettes, nine women are celebrated as forgotten leaders. Leah Chase hosted meetings in her home, cooking gumbo, literally feeding and housing the fight for justice. Aileen Hernandez rose from the segregated streets of Washington DC to become the first woman and first Black appointee to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Each story fills in another blank space in the widely erased history of women in the civil rights movement.

The lesson and curriculum that sprouts from Hidden Figures has served me effectively in my own courses on the civil rights movement and feminism. My hope is that this pedagogy prompts others to engage in their own projects on forgotten figures of the past and to further expand lessons already underway.