What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore —

And then run?

…Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

This passage from “Harlem,” a poem by Langston Hughes, has been described as a “virtual anthem of black America.” As a poet, playwright, fiction writer, autobiographer, and anthologist, Hughes captured the moods and rhythms of the black communities he knew and loved—and translated those rhythms to the printed page. Hughes has been called “the literary explicator and interpreter of the social, cultural, spiritual, and emotional experiences of Black America.” This grand description is accurate for the role his writings have played in 20th-century American literature.

Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902. His father, a lawyer frustrated by American racism, moved to Mexico when Hughes was a year old, and Hughes spent most of his childhood at his maternal grandmother’s home in Lawrence, Kansas. His grandmother had been an activist for decades. Her first husband was killed at the slave rebellion at Harpers Ferry. Her second husband, Hughes’s grandfather, was the brother of abolitionist John Mercer Langston and a participant in Kansas politics during Reconstruction. In his grandmother’s home, Hughes was part of a close-knit black community, and he was always encouraged to read.

As a teenager, Hughes lived with his mother in Lincoln, Illinois, and Cleveland, Ohio. In Cleveland, he contributed to his high school literary magazine, was elected class poet his senior year, and graduated from high school in 1920. Hughes then spent a year in Mexico with his father. A poem he wrote on the train ride there, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” was published in the June 1921 issue of The Crisis, the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). It is still perhaps his best-known poem, and it instantly confirmed his potential as a serious writer.

At his father’s wish, Hughes enrolled at Columbia University in New York City in the fall of 1921, but he stayed only one year and spent most of his time in Harlem, in upper Manhattan. He took a series of jobs that included traveling down the west coast of Africa and then to Europe as a crewmember on a merchant steamer. Hughes continued writing poetry during his travels, publishing much of it in the United States in black journals such as The Crisis and the publication of the National Urban League, Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life. By the time he returned to the United States in 1924, his reputation was already established. He won first prize in Opportunity’s 1925 poetry contest for his poem “The Weary Blues,” and the following year Alfred A. Knopf published The Weary Blues, Hughes’s first volume of poetry.

By this time, Hughes was recognized as one of the leading figures in the constellation of black writers, artists, and musicians in New York who created the Harlem Renaissance, a cultural movement of the late 1920s and early 1930s. Hughes’s poetry was greatly influenced by the people and culture around him. He admired the narrative style of white poets Carl Sandburg and Walt Whitman, but was also influenced by the poems of Paul Laurence Dunbar written in black dialect, and he incorporated the rhythms of black speech into many of his poems. Above all, Hughes was influenced by black music, especially jazz and blues.

Hughes’s poems are often lyrical in the musical sense of the word—many of them could easily be set to a rhythmic beat. They also incorporate some of the same subject matter found in many blues lyrics, and portray nuances of black life—including sexuality—missing in earlier black literature. In a 1926 essay titled “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes eloquently defended the honest representations of black culture and the use of jazz, dialect, and other influences from the black vernacular that had become a trademark in the work of many Harlem Renaissance writers. As Hughes put it, “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame.”

Hughes enrolled in Lincoln University in Lincoln, Pennsylvania, in 1926, and graduated in 1929. The next year he published his first novel, Not Without Laughter. After an argument with a white patron who had been supporting him financially, Hughes spent time traveling, making extended visits to Haiti, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), and Carmel, California. He had begun publishing in the journal sponsored by the Communist Party, New Masses, even before he began to travel, and wrote some of his most politically radical poetry while in the USSR.

In Carmel, Hughes wrote his first collection of short stories, The Ways of White Folks (1934). He finished the decade with several successful plays, including Mulatto, loosely based on his grandfather’s family. Mulatto opened on Broadway in 1935 and became the longest running Broadway play by an African American until A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry nearly 25 years later.

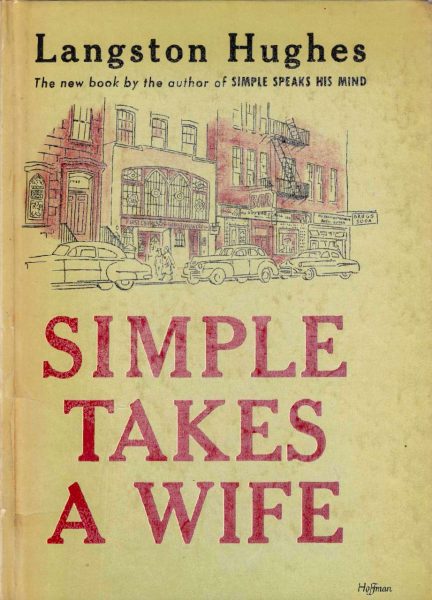

In 1940 Hughes published his first autobiography, The Big Sea. In it, he discusses his childhood, his estrangement from his father, and other personal topics, but readers especially value its insider’s portrayal of the Harlem Renaissance. Two years later, he began writing a weekly column for the Chicago Defender that unexpectedly spawned his most popular literary character, Jesse B. Semple. “Simple,” as he was called, was a fictional Harlem resident who had little education but many street-smart opinions on everything from World War II to American race relations. Simple became a representative for the black Everyman. Over the next 20 years, in addition to his column, Hughes published five books and an off-Broadway play that featured Simple, who has been called “one of the more original comic creations in American journalism.”

Hughes also published more poetry and plays in the 1940s, and as lyricist for the 1947 Broadway musical Street Scene he earned enough money to buy the Harlem home where he lived for the rest of his life. In 1951 Hughes published one of his most important poetry collections, Montage of a Dream Deferred, which contained well-known works such as “Harlem” and “Dream Boogie.” During the 1950s, Hughes published two more collections of short stories, another novel, several nonfiction works of children’s literature, and his second autobiography, I Wonder as I Wander (1956).

In the 1960s Hughes wrote several successful plays featuring gospel music, including Black Nativity (1961), which remains a holiday tradition in several cities, and Jericho-Jim Crow (1964), based on the Civil Rights Movement. He also published anthologies of poetry, short stories, and humor, and the book-length poem Ask Your Mama (1962). When he died on May 22, 1967, he was at work on a new collection of poetry celebrating the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, which was published later that year as The Panther and the Lash.

As a writer, Hughes was prolific, both in the genres he covered and the amount he produced, and he became the first African American author able to support himself completely by his writing. But his work was remarkable for much more than its quantity. Hughes’s writing captured the essence of black America in a way black Americans felt it had not been captured before. As biographer Arnold Rampersad said, “From the start, Hughes’s art was responsive to the needs and emotions of the black world…. Arguably, Langston Hughes was black America’s most original poet. Certainly he was black America’s most representative writer and a significant figure in world literature in the 20th century.”

Contributed By: Lisa Clayton Robinson