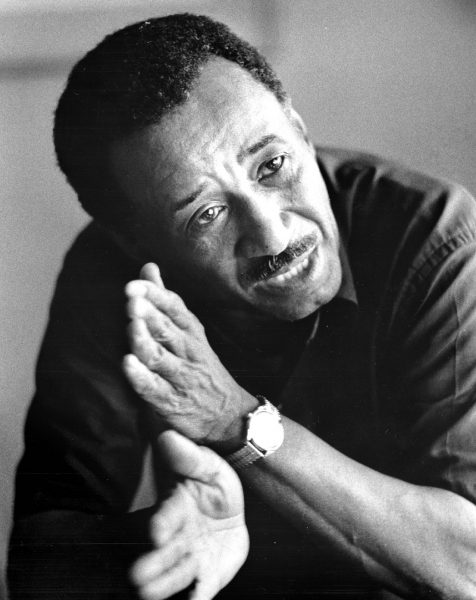

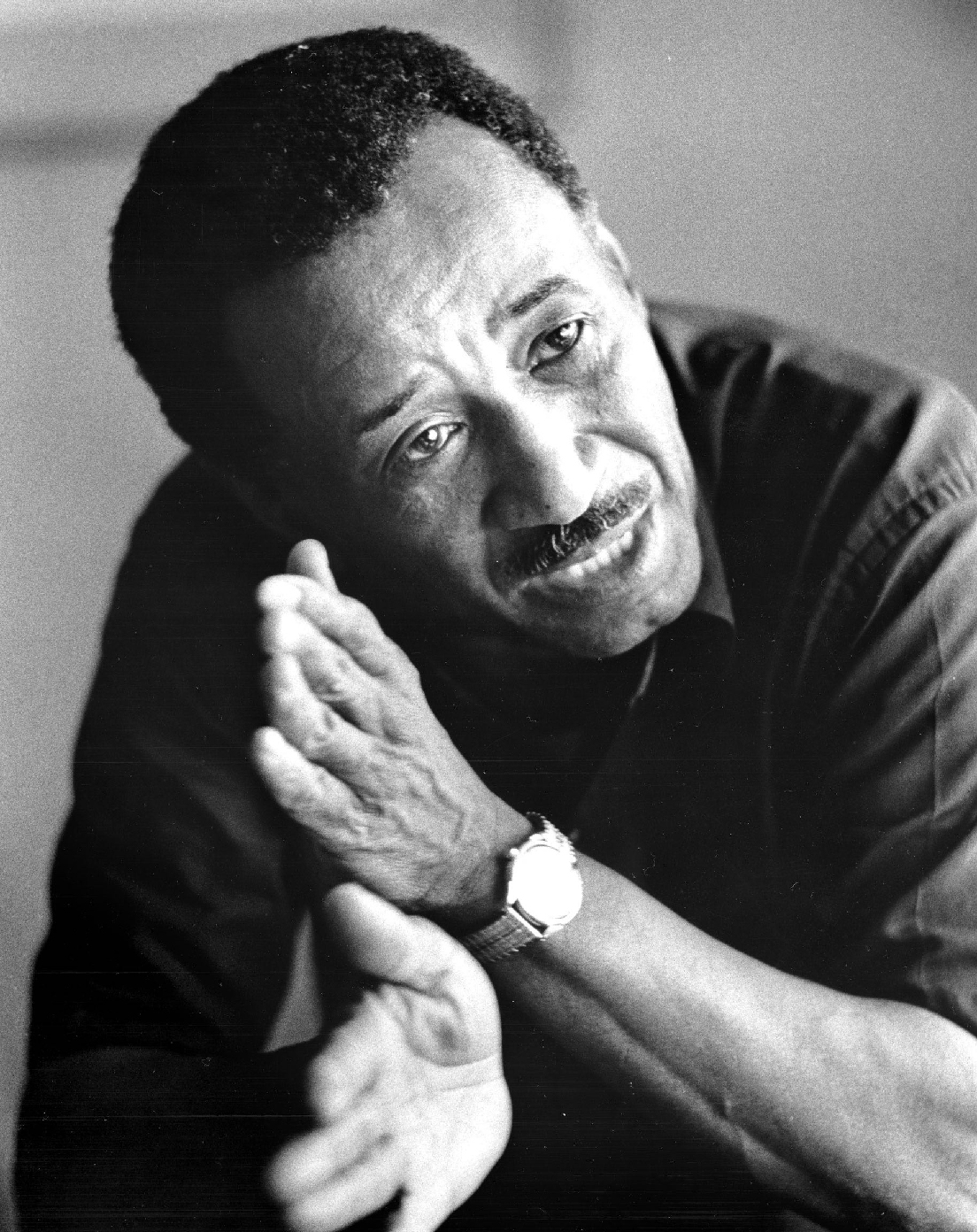

Adopted by Albert Lee Murray and his wife, Mattie James Murray, Albert Murray grew up in Magazine Point, outside of Mobile. Often characterized as a member of the “Talented Tenth,” Murray excelled academically and won a scholarship to Tuskegee Institute in 1935. Following his graduate study at the University of Michigan, he returned to Tuskegee to teach English and theater. In 1943, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force and was in the service until 1962 when he retired as a major. During the years of his retirement, Murray has lived mostly in New York City but has been a visiting professor in various schools including Colgate, Barnard, Columbia, Emory, the University of Massachusetts at Boston, and Washington and Lee.

Like his friend and Tuskegee classmate, Ralph Ellison, Murray is interested in the cultural complexity of America, especially for African Americans. He strongly contends that African culture permeates American life. Murray’s first published work, The Omni-Americans (1970), is a compilation of essays in which he presents himself as an ardent critic of theories that contend that African Americans are subservient to white social infrastructures. Murray views African American culture as an advantageous extension of the American self.

In his second work, South to a Very Old Place (1971), Murray offers autobiographical appeal to his social theory. The book guides the reader through the South from New York to Mobile with Murray as mediator. South to a Very Old Place centers around balancing and understanding the relationship between black and white, oral tradition and journalism, and past and present. Other works include a collection of public lectures given at the University of Missouri, entitled The Hero and the Blues (1973), emphasizing the natural synthesis of blues ballads and prose.

Train Whistle Guitar (1974) was the first of a fiction trilogy, followed by The Spyglass Tree (1991) and Seven League Boots. These novels trace the life of a bright young man named Scooter, Murray’s fictional alter ego. Train Whistle Guitar won the Lillian Smith Award for Southern Fiction; its intertwining of rhythm and use of vernacular is attributed to the author’s passion for the blues and his efforts to place them on the page. Stomping the Blues (1976) pays homage to Murray’s tenet of the “vernacular imperative,” transcending everyday life into aesthetic. Within this framework, Murray transforms the rhythmic, improvisational style of jazz and the blues into prose.

Good Morning Blues (1985), the autobiography of Count Basie as narrated by Murray, is his ultimate tribute to the aesthetic, stepping into the shoes of a black jazz artist. The Blue Devils of Nada (1996), Murray presents essays analyzing some of his favorite artists (Ellington, Hemingway, Bearden), using tenets of both blues and prose in American culture.

Contributed By: Eva Marie Stahl