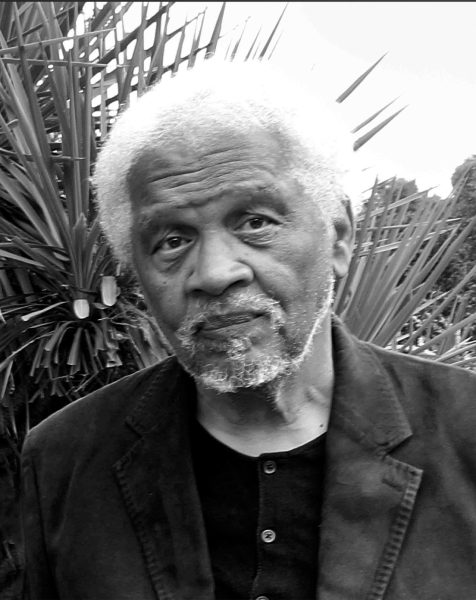

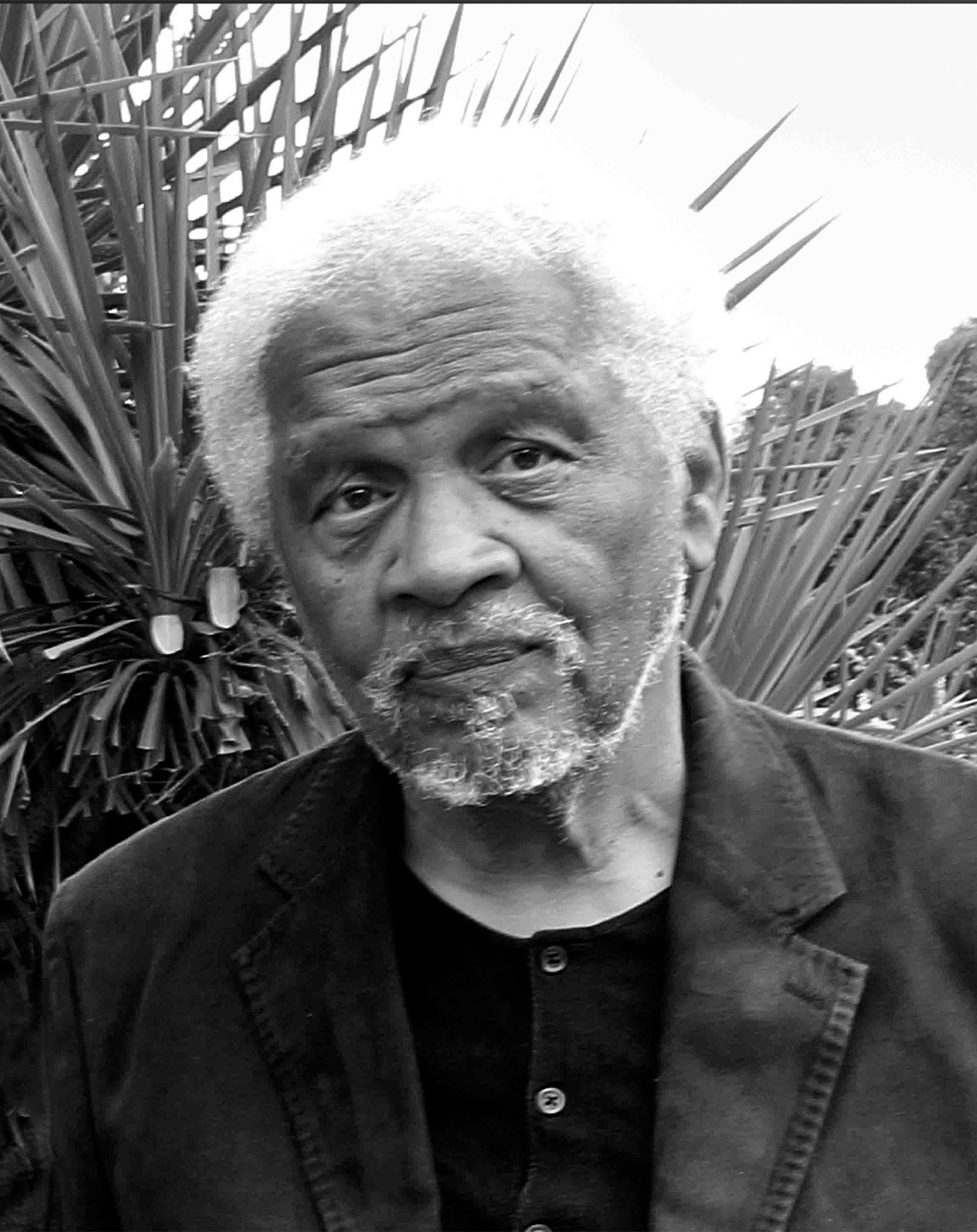

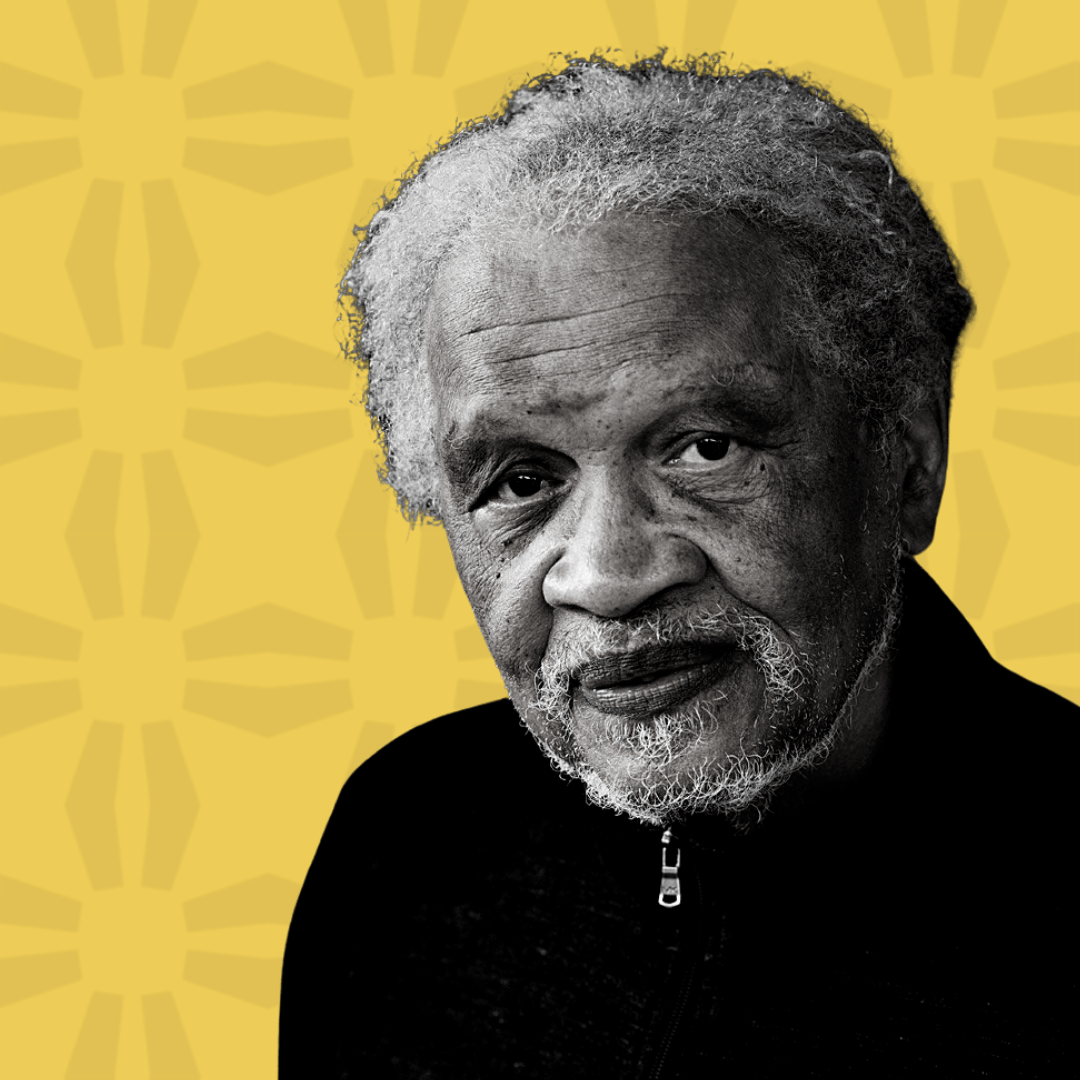

Ishmael Scott Reed, poet, novelist, playwright, lyricist, cartoonist, musician and founder of small presses and publications, has remade literature. He has done so across six decades with satire, curiosity, teaching and an increasingly global reach.

Known as “Uncle Ish” to his many admirers, the MacArthur Foundation “genius” from 1998 remains a fierce critic of the tokenism of multi-cultural artists and of establishment media. He lives in California and calls himself “a writer in exile” because he finds it easier to be published abroad. Now 84, The New Yorker magazine positioned Reed in 2021 as “America’s most fearless satirist.”

The writer best known for the groundbreaking novel “Mumbo Jumbo” will see its 50th anniversary edition out from Scribner this year. It tells a Harlem detective story set in motion by “Jes Grew,” a virus of freedom and polytheism spread by Black artists, starting in New Orleans. Both the Yale-enshrined critic Harold Bloom and the funk artist George Clinton proclaimed its beauty and merit, Clinton proclaiming that Reed was doing funk before he was. Tupac Shakur cited Reed in his song “Still I Rise.”

Reed’s early poetry collection, “Conjure,” also excited critical attention and inspired a musical group of the same name to perform his songs. The group claims the mantle of the longest poetry/jazz collaboration in history. Reed has written songs for Gregory Porter, Macy Gray, Taj Mahal, Bobby Womack, Mary Wilson of the Supremes, and Little Jimmy Scott. He made his own debut as a jazz pianist in 2007 with “For All We Know” by the Ishmael Reed quintet featuring David Murray. His forthcoming album is “Hands of Grace.”

The crosshatch of Reed’s influence over six decades is astonishing, and it began early: he introduced the poetry of Lucille Clifton, his fellow Buffalo, N.Y., writer, to Langston Hughes, who published the work in “The Poetry of the Negro,” her first national exposure. Hughes in turn introduced Reed to Anne Freedgood, an editor at Doubleday who, in 1967, acquired Reed’s first novel, “The Free-Lance Pallbearers.” She edited “Mumbo Jumbo,” “The Last Days of Louisiana Red” and “Flight to Canada.”

Born in Chattanooga in 1938, Reed’s mother Thelma moved them to Buffalo, where she married Bennie Reed, who worked on the Chevrolet assembly line. In her own book, “Black Girl from Tannery Flats,” she describes her son as inquisitive, an old soul who scolded adults for their expensive shoes and lackadaisical newspaper reading habits.

A.J. Smitherman, the legendary editor of The Empire Star and hero of the uprising against lynching in Tulsa in 1921, recruited a 16-year-old Ishmael as a delivery boy, then as a jazz columnist for the Black newspaper. After Smitherman’s death, Reed and Joe Walker, both young men, put out the paper. Their radio show, Buffalo Community Round Table, was canceled after they hosted Malcolm X. The encounter inspired Reed to move — belongings stuffed in a single laundry bag — to New York City in 1962.

Reed found other Black artists, musicians, and writers through the Umbra Workshop, led by Tom Dent and Calvin Hernton. Some members would foment the Black Arts Movement. Reed likes to joke he wasn’t a member, but the first patron. By 1967, Reed and Carla Blank, a Judson dancer and choreographer who first noticed his expressive hands, were headed for California. Reed was determined not to become a token of the New York publishing establishment. He saw it as a guarantee that a bullseye would land on his back.

Instead, Blank and Reed married, and together nurtured a host of creative tendrils. Blank directed Reed’s play “Mother Hubbard” in Hunan, China. She became editorial director of Ishmael Reed Publishing Company, and their daughter Tennessee, a photographer and poet, became managing editor of Reed’s online publication, Konch.

All the while, Reed was becoming a gravitational force in California, teaching for more than 30 years at the University of California, Berkeley. He was the first to publish students Terry McMillan, poet John Keene and Mona Simpson, now the editor of The Paris Review. Anisfield-Wolf recipient Colson Whitehead told Julian Lucas of The New Yorker, “Some folks dream about being in Harlem during the 20s . . . I’m sad I didn’t get to hang out in the late 60s Berkeley with Ishmael Reed.”

Reed’s aesthetic is multi-cultural; he writes poetry in Japanese and translates Yoruba into English. He has long ties with Indigenous, Spanish-speaking and Asian American artists and is the founder of two literary organizations, The Before Columbus Foundation and PEN Oakland. There, Reed won the Chancellor’s Award for Community Service and saw his name floated as a mayoral candidate.

Still, Reed’s sensibility stands resolutely with the Black working class. “We do have a heritage,” Reed is quoted in The New Yorker. “You may think it’s scummy and low-down and funky and homespun, but it’s there. I think it’s beautiful. I’d invite it to dinner.”

When the big MacArthur Foundation payday arrived, Reed spent it partly on financing an opera in Berkeley, New York and San Francisco that he called a “Gospera.” He also financed theater in which the Black actors needn’t play maids or prostitutes. In 2016, he received the Alberto Dubito International award for poetry in Venice.

Three years later, Reed’s off-Broadway play, “The Haunting of Lin-Manuel Miranda,” skewered the “Hamilton” playwright for painting his subject as “an ardent abolitionist” when the man owned people. Reed’s follow-up play, “The Slave Who Loved Caviar,” depicts a vampire-like relationship between Andy Warhol and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

The spate of Black Lives Matter-inspired reading lists rouse his suspicions, dismissed to Lucas as a scroll of “life-coaching books about how to get along with Black people.” Anti-racism, he continued, “is the new yoga.”

In 2020, the University of California, Berkeley, named Reed Emeritus of the Year. “Ishmael is an enormously charismatic and effective teacher,” said Jeffrey D. Knapp, who chairs the English department. “He is probably our most prolific faculty member.” His most recent poetry collection is “Why the Black Hole Sings the Blues.”

Reed is currently a distinguished professor at the California College of Arts. More than a half-century after their arrival, he and Blank work and live in Oakland.