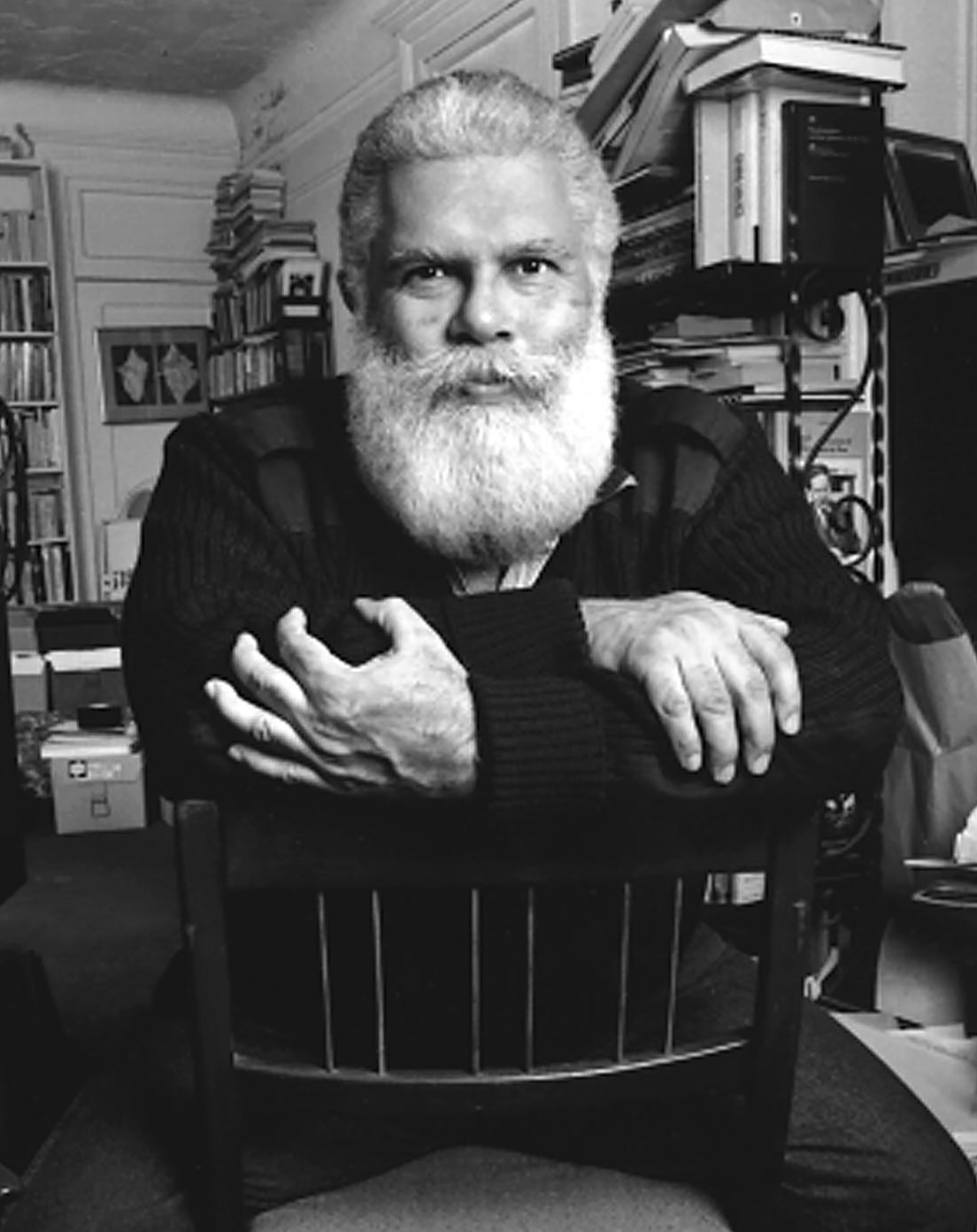

James McBride has worn a porkpie hat, a goatee and a wry smile on his way to becoming a celebrated artist, Spike Lee collaborator and a National Humanities Medalist. President Barack Obama lauded him on that 2015 occasion for “humanizing the complexities of discussing race in America” and displaying “the character of the American family.”

The novelist, musician, composer and screenwriter was born in 1957 to Ruth McBride, a new widow in a Brooklyn, N.Y. housing project, the eighth of her 12 children. His mother and father, the Rev. Andrew McBride, had started the New Brown Memorial Baptist Church, a small place that still figures prominently in their son’s life.

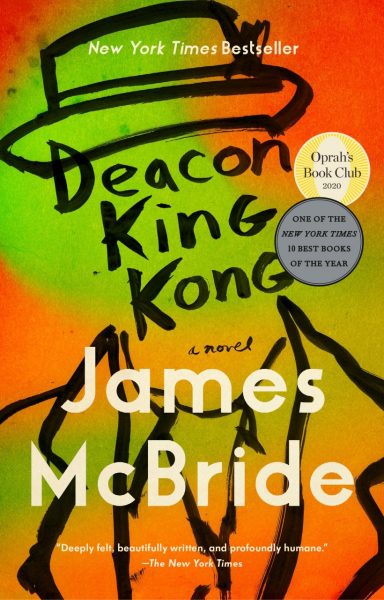

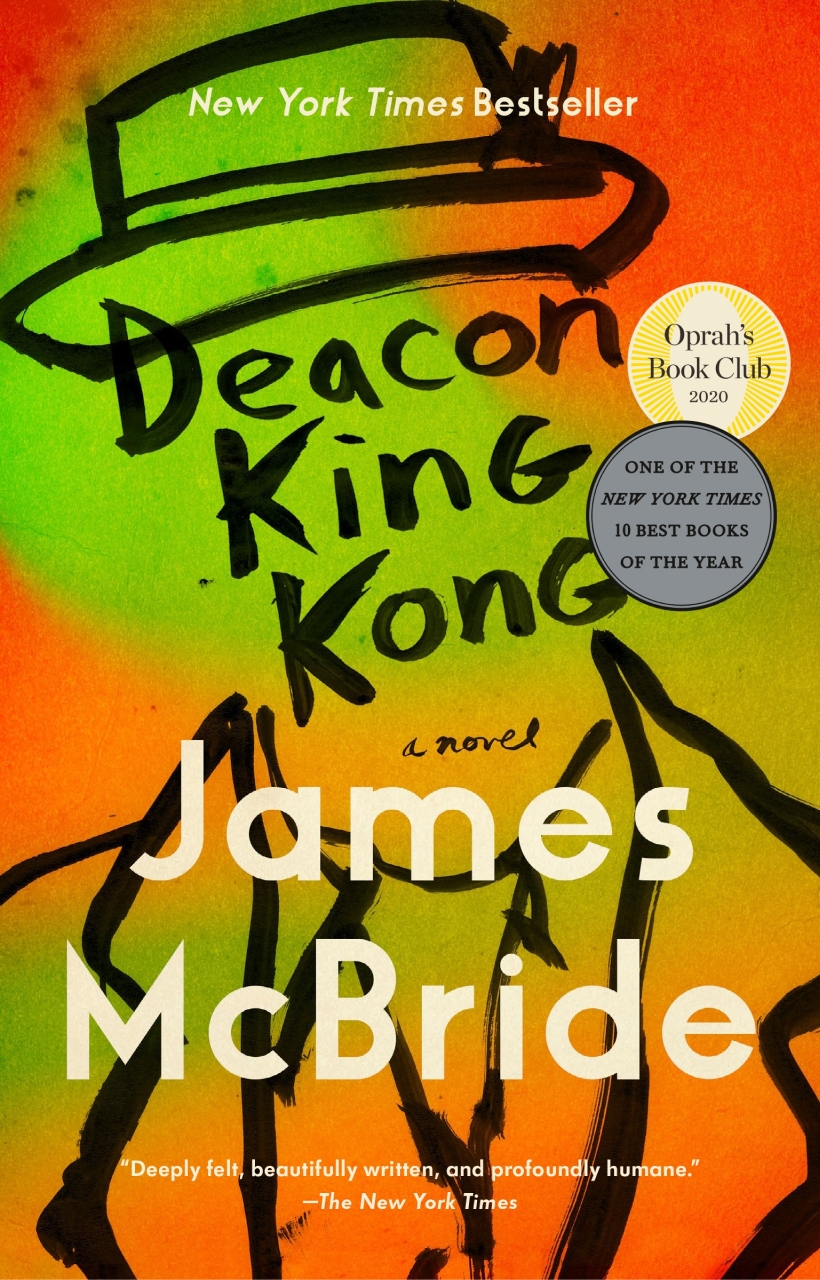

A fictionalized version of that church, Five Ends Baptist, anchors and animates Deacon King Kong, a rollicking tale set spinning in 1969 by an elderly, alcoholic deacon who crosses a courtyard full of neighbors to shoot an ear off the most notorious drug dealer in the history of the local housing projects. King Kong is the name of the deacon’s favorite home-brewed hooch.

“Deacon King Kong is sort of a benign variant of ‘The Wire,’” observes Joyce Carol Oates, an Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards juror. “It is robust and funny, confronting tragedy with an ebullient comic spirit, ‘pulling its punches’ in unexpected ways that repudiate disaster and resound just right.”

McBride traces his musicality to church and home. His first book chronicles his remarkable mother, her Orthodox Jewish roots, her two marriages to Black men and her embarrassing, clunky bicycle, a story familiar to the millions of readers of The Color of Water. McBride subtitled his 1996 memoir: A Black Man’s Tribute to His White Mother. Told in alternating mother/son chapters, it won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award, spent more than two years on the bestseller lists and entered the international literary canon.

Asked in 2013 by the New York Times if he identified with any literary characters growing up, McBride said, “Not really. My mother was more interesting and mysterious than any literary character I’d ever come across.”

She stressed two paramount virtues: education and church. James attended New York City public schools, then earned a degree in music composition from Oberlin College in 1979. There followed some “wonderful but lean” years playing saxophone as a sideman for jazz singer Little Jimmy Scott, writing songs for headliners such as Anita Baker and composing an off-Broadway musical called Bobos that won a Stephen Sondheim Award.

A journalism degree from Columbia University led to newspaper staff writing jobs at the Boston Globe and Washington Post, then a few stabs at writing fiction during a stint at People magazine that included covering Michael Jackson’s “Victory” tour. “It was terrible fiction,” McBride told The New York Times, “but I just needed a way out. I wasn’t a guy built to write about entertainment.”

But McBride could summon an unerring comic touch. “He’s profound,” said friend Bobby Ferrazza, an Oberlin jazz professor. “He’s also funny. He’s said some of the funniest things I’ve heard in my life.”

The judges for the National Book Award agreed, anointing in 2013 The Good Lord Bird,” a picaresque fictional retelling of abolitionist John Brown’s tale through the eyes of a child he kidnaps and calls Little Onion.

“I don’t like serious books too much,” McBride told Edan Lepucki in an interview for the National Book Foundation. “I don’t like books that say, essentially, ‘Take your medicine.’ They depress me. I wanted to write a book that would make folks laugh and still inform them. I wanted John Brown to be as popular in American mythology, as, say, Jesse James, who was, among other things, a slaveholder and a killer. Also, caricature drives a straight line to the truth.”

Ethan Hawke, who plays Captain John Brown in the seven-part Showtime series of the novel, told National Public Radio that “the magic trick that McBride does by telling the story through Onion’s point of view is he lets you laugh about it. He [writes] the humanness into it, as opposed to a political angle. It’s not self-serious, and yet it’s full of tremendous heart. McBride finds a way to make it a healing experience.”

The way McBride tells it, he needed a healing himself when he wrote Deacon King Kong. Bruised by a bad divorce, still mourning the deaths of his mother and a niece, McBride told an audience at the Politics and Prose bookstore, “I said to God, ‘If you get me out of this, I will serve you for the rest of my life.’ And God got me out of it. He did. It’s easy to walk away but it’s better to stay and do the work.”

That work features being a “choir dad” at his parents’ church in his old Brooklyn neighborhood, “growing our own garden” of musicians. All the while, McBride taught at New York University and crafted his latest novel.

It “is many things: a mystery novel, a crime novel, an urban farce, a portrait of a project community,” writes Junot Diaz, an Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards winner for The Brief, Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. “There’s even some western in here. The novel is, in other words, a lot. Fortunately, it’s also deeply felt, beautifully written and profoundly humane; McBride’s ability to inhabit his characters’ foibled, all-too-human interiority helps transform a fine book into a great one.”

Asked by The New York Times if he could be any character in literature, McBride answered Spiderman.

“If that doesn’t count, George Smiley from John le Carré’s early work,” he added. “Smiley understands. Smiley takes it across the face. Smiley’s got a job to do. Smiley’s got a broken heart. Smiley can take it.”

McBride splits his time between Lambertville, N.J., and New York City. He has three children.

Deacon King Kong