This weighty book intends to “tell the story of slave life as carefully and accurately as possible.” Less given over to theoretical and topical polemic than Genovese’s earlier works on Southern slavery, it is by no means a catalogue. It amplifies Genovese’s stress on the humanity slaves were able to preserve through de facto accommodations on the part of both slave and master, through the reciprocal play of “elementary human reactions” across class and color lines, and through the slaves’ “strong sense of stewardship” for one another.

This is a necessary transcendence of many other historians’ dehumanizing view of both slaves and slaveholders, and to it Genovese brings his intellectual expansiveness and depth of feeling as he further documents key points featured in The World the Slaveholders Made (1969) and The Red and the Black (1972): the resourcefulness and egalitarianism of many house servants, the protective, responsible character of many black drivers, the prevalence of family stability and the nourishment Christianity afforded against degradation. Some critics will argue persuasively that Genovese has not done justice to southern slavery’s deprivation, brutality and murder. As a matter of page-by-page arithmetic, Genovese certainly places more weight on young folks’ play by the cabin door than on “evidence of widespread dirt-eating.” The question – raised very differently by Fogel and Engerman in Time on the Cross, whose econometric inferences crosshatch Genovese’s view – is one of method and concept in shaping the evidence.

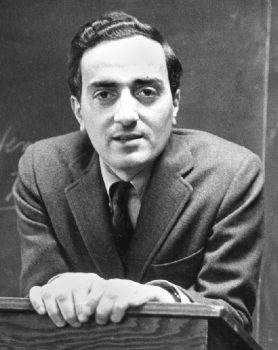

Eugene Dominic Genovese is an American historian of the American South and American slavery. He has been noted for bringing a Marxist perspective to the study of power, class and relations between planters and slaves in the South. His work Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made won the Bancroft Prize. Since then, however, he has abandoned the Left and Marxism and embraced traditionalist conservatism.