by Charles Ellenbogen

Ray Carney has a problem any parent will recognize. The protagonist of “Crook Manifesto” – the second in Colson Whitehead’s Harlem trilogy — has a daughter, May, craving tickets to the Jackson 5 concert, which is sold out. Carney, a once part-time crook trying to become a full-time furniture salesman, still has connections and taps into them in exchange for a promise of concert tickets. He agrees to do a favor and, as any casual reader of crime novels can predict, this leads him into a much more tangled and serious situation than he anticipated.

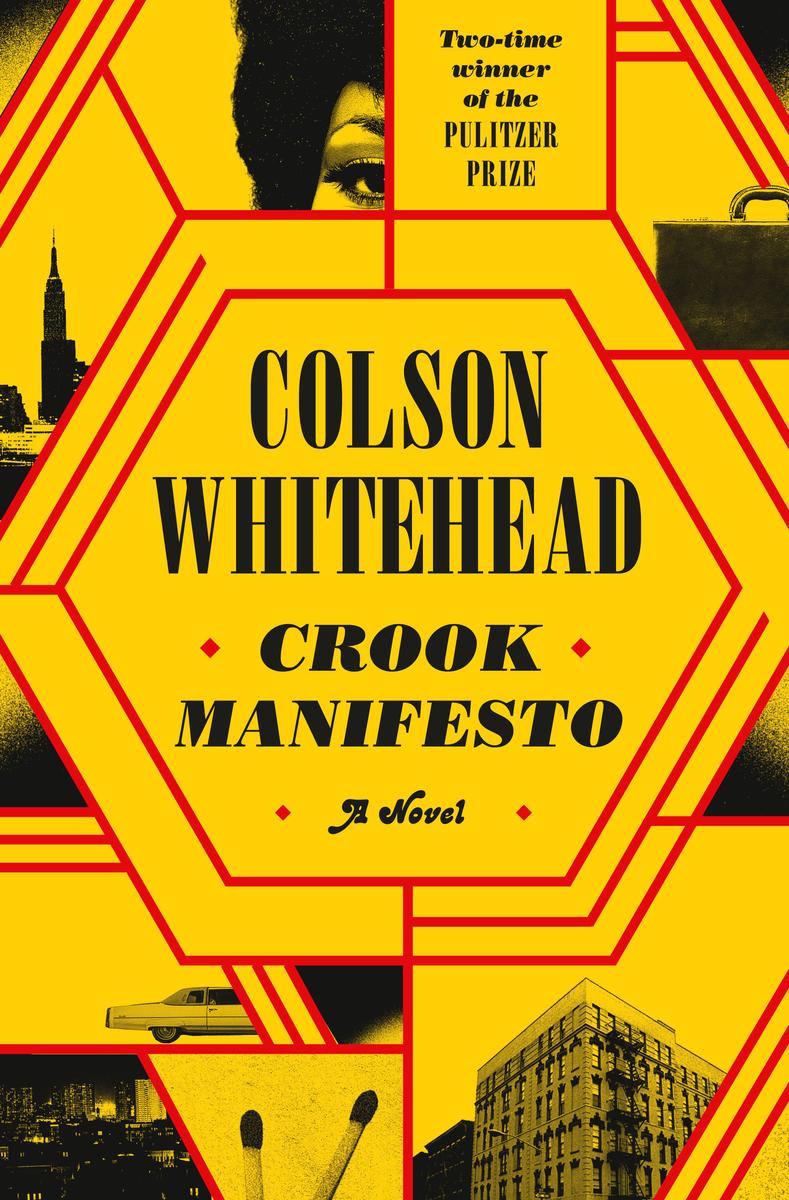

Those seeking an innovative plot are better served by Whitehead’s “The Underground Railroad” and “The Nickel Boys” (both won Pulitzer Prizes) or “John Henry Days,” which earned an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award more than 20 years ago.

Instead, “Harlem Shuffle” rewards readers with its language, character, setting, and commentary.

Of New York City (the very definitely a character), Whitehead writes in an Algrenesque style, “City like this, it behooves you to embrace the fucking contradictions.” Note the absence of the “In a” and the contradiction within the statement about contradictions; the same person uses the word ‘behooves’ and a profanity in one breath.

The camera doesn’t just stay on Carney, though. Whitehead places Pepper center stage in the second section of the novel. We first meet him when he’s working security: “His technique: glaring with his arms loosely crossed; lifting a skeptical eyebrow when civilians got too close to the perimeter; the occasional grunt to warn someone off. He was a six-foot frown molded by black magic into human form. It sufficed.”

This novel makes brilliant use of short phrases and punctuation. Consider those final two words “It sufficed.” The reader falls into rooting for Pepper. What places this novel squarely in the five-star ranks, though, is Whitehead’s commentary. While many crime novels might incidentally have a comment to offer about the wealthy class in Los Angeles, Whitehead’s trilogy is, in the end, a loving and critical history of Harlem.

On the surface, each of the three sections of this story are centered around an historical event – the last, in 1976, is infused with New York’s celebration of the U.S. Bicentennial. The upcoming holiday sets Carney scrambling for an advertising tie-in. One possibility? “Two hundred years of getting away with it.” Neither Carney nor Whitehead need to define “it.” It’s in the city’s and the nation’s DNA.

Based on “Harlem Shuffle” and “Crook Manifesto,” Whitehead seems to be aligned with James Baldwin, who wrote, “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.”

The corruption, the fires, the neglect, the architecture, the poor, the wealthy, the music, the food, the police, the criminals and the furniture – Whitehead sees them all as intertwined, all as part of the problem, as part of the legend. People, mostly white though sometimes Black, keep finding ways to profit off Harlem. As the city struggles with bankruptcy, even Hollywood finds a way to make money off people like Ray Carney. Just as he can’t stay away from his criminal past, none of the city’s elements can disentangle. It seems Carney and Whitehead wouldn’t want it any other way.

The ending, though, will leave you wondering how Carney will respond to New York in the upcoming third novel.