For most of her childhood, professor Daisy Hernández, believed her aunt Dora Capunay Sosa died from eating a contaminated apple. It wasn’t until adulthood that she understood the disease that killed her aunt and ten thousand others each year: chagas.

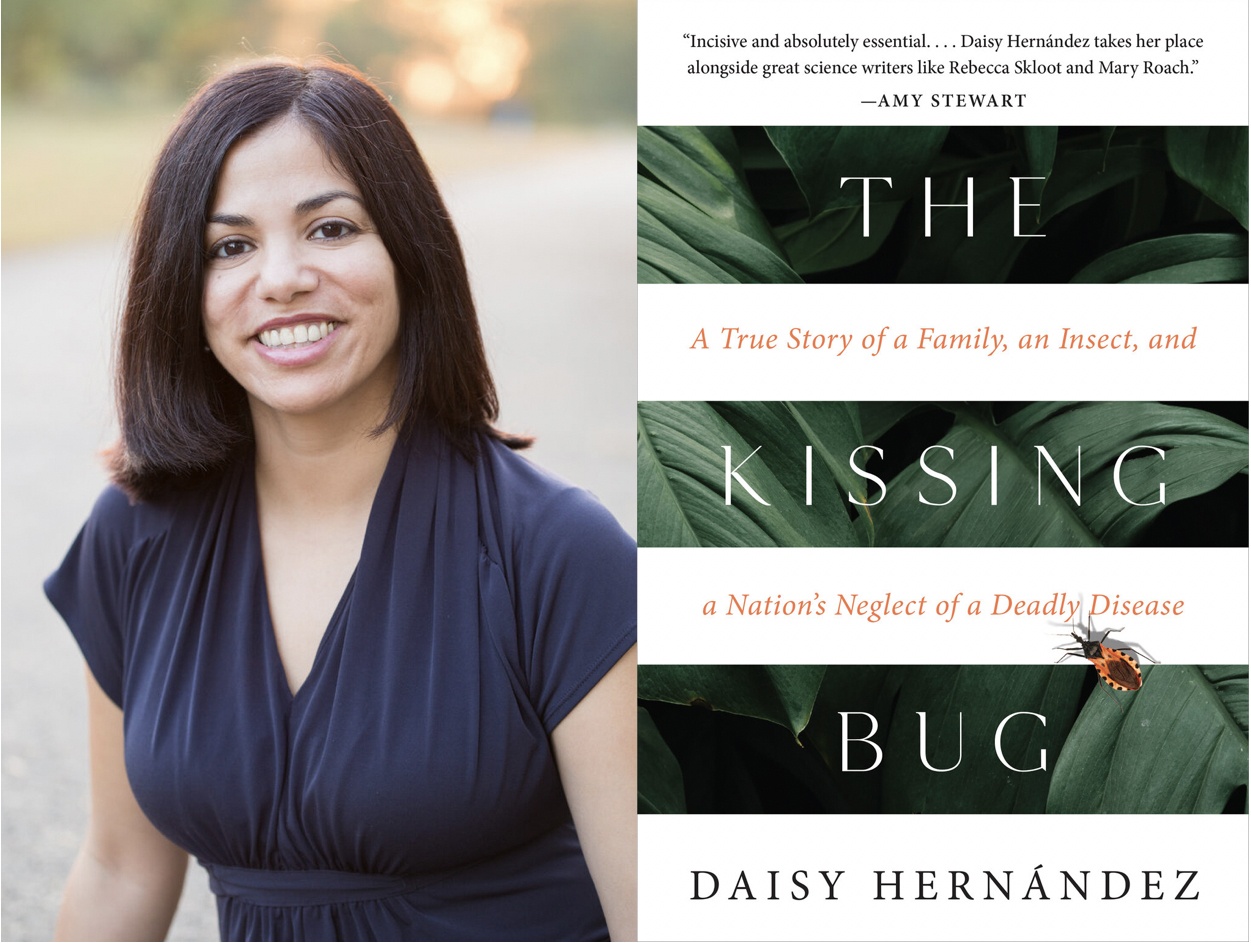

Hernández tells her aunt’s story in “The Kissing Bug,” an intimate, meticulous investigation into an illness that disproportionately affects the Latinx community.

Chagas, named after the Brazilian doctor who described it in 1909, is similar to Lyme disease in that it is not the insect itself that harms the heart and digestive system, but the parasite it carries. These triatomine bugs or “kissing bugs” are found in warm, rural regions, flourishing in the southern United States, Mexico, Central America and South America.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates nearly 300,000 people in the U.S. live with the parasitic infection, nearly all of them immigrants. Another six million carry it outside these borders. But it’s infuriatingly unpredictable — after decades of study, doctors still can’t pinpoint which patients will develop life-threatening symptoms.

In the opening chapter, Hernández, a Miami University professor, explains that the parasite can live in the body undetected for decades, “quietly interrupting the electric currents of the heart, devouring the heart muscle, leaving behind pockets where once healthy tissue existed.”

In some cases, like her Aunt Dora, it will also attack the digestive system. After an exploratory surgery in Colombia, doctors told Hernández’ family that Dora’s large intestine had grown to the point she “had enough for 10 people.”

“This could have easily been a 700-page book,” Hernández said, speaking to an attentive audience at Hiram College in late March. She spent seven years researching not only her family history but crisscrossing the country to find patients and doctors to speak on the history of this little-understood, marginalized disease.

“It is really challenging because you have to not only find a patient but find a patient willing to spend hours with you,” Hernández said. “And in my case, I wanted to interview them over the course of several years.”

One patient, Carlos, slept next to a stack of overdue bills from mounting medical costs, sharing a one-bedroom apartment with his three brothers. Hernández met him as a patient whose heart had been decimated by the disease; she later served as his interpreter at an appointment following a successful heart transplant.

“The Kissing Bug” is Hernández’ third book, after serving as co-editor of 2002’s “Colonize This! Young Women of Color on Today’s Feminism” and releasing her memoir “A Cup of Water Under My Bed” in 2014.

“The continuity for me has been Latinx communities and intersectionality and racial justice issues,” she noted.

Hernández quoted a piece of advice from writer Cherrie Moraga: “Some of us have to write the memoir first because we have to clear everything out so a different story can come through. I definitely felt that way with ‘A Cup of Water.’ A memoir of growing up with this immigrant family, with being queer, of having an alcoholic parent, really difficult dynamics, being the first in my family to go to college and have that experience in the U.S….I needed to write all of those stories so I could have space for other stories. I could not have written this book before my memoir.”

Hernández shared that a deleted chapter on America’s link between citizenship and access to health care might find its way into her next book: “Don’t hold me to that, if seven years from now you see me with a very different book,” she joked.

Early this year, Hernández became the first Latina to win the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award, which recognizes a book for its originality, merit, and impact, and for breaking “new ground by reshaping the boundaries of its form and signaling strong potential for lasting influence.”