The holiday of Juneteenth is deepening its mark on American history.

The U.S. Senate voted unanimously this week to make June 19 an official national holiday, leaving the House of Representatives to take an expected yea vote giving federal workers a new paid day off.

The day marks the moment in Galveston, Tex., when people in bondage learned that slavery was finished, two years after President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation and two months after Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

African Americans, particularly in Texas, have honored June 19, 1865, shortened to “Juneteenth,” with picnics, parades and pilgrimages to Galveston since enslaved men on the wharfs whooped at the news (and some were beaten for it). The halting story of how the rest of the nation caught up is worth telling.

And so, when the coronavirus pandemic sealed many New Yorkers into their apartments, historian Annette Gordon-Reed turned to the task. Bob Weil, her editor at W.W. Norton, had long encouraged her to write about Texas, where she had grown up.

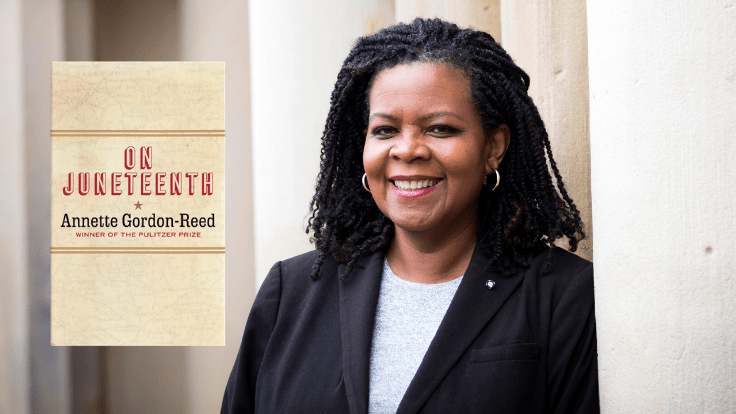

The result is “On Juneteenth,” a nuanced, concise 148-page reflection in six chapters that twines some of her own family story with her home state, “this most American place,” as she puts it.

She writes that the “Cowboy, the Rancher, the Oilman – all wearing ten-gallon hats or Stetson – dominate as the embodiments of Texas. Of greater importance, as I have said in another context, the image of Texas has a gender and a race: ‘Texas is a White man.’ What that means for everyone who lives in Texas and is not a White man is part of what I hope to explore in the essays of this book.”

Indeed, such a potent reductive stew in the popular imagination makes Texas ripe for misunderstanding. At the taproot of Texas is Stephen F. Austin, who recruited white people to the Mexican province of Coahuila y Tejas, now East Texas, not to wrangle or drill but to clear the land for cotton. And Austin, a Missouri scion of slaveholders, discouraged the new arrivals from doing that work themselves.

Yet, Austin, whose name now graces a state capitol and the site of a hip music festival, is just one strand in a more complex origin story.

“No other state brings together so many disparate and defining characteristics all in one,” Gordon-Reed writes, “a state that shares a border with a foreign nation, a state with a long history of disputes between Europeans and an Indigenous population and between Anglo-Europeans and people of Spanish origin, a state that had existed as an independent nation, that had plantation-based slavery and legalized Jim Crow.”

This slim book is a testament to the reading pleasure to be had in the hands of an accomplished, lucid and to-the-point scholar. “On Juneteenth” is an excellent primer for a traveler wanting their bearings before visiting Texas.

Gordon-Reed, 62, is the Carl M. Loeb University Professor at Harvard, a recipient of a MacArthur Foundation “genius” grant and an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for her definitive, history-correcting “The Hemingses of Monticello.” She took her forensic, legal scholarship into the primary documents of the family life and tree of Thomas Jefferson and gave the Hemingses side its due.

Gordon-Reed’s own family tree is fascinating; her maternal side traces to the 1820s in Texas; her paternal to at least the 1860s. Juneteenth was no abstraction in her household.

“Juneteenth was different,” she writes of the day’s contrast to July 4. “For my great-grandmother, my grandparents and relatives of their generation, this was the celebration of the freedom of people they had actually known. My great-grandmother’s mother had been married three times, outliving all her husbands. Her last one had been enslaved until the end of the Civil War.”

Gordon-Reed played her own role in local history in East Texas, where she was the first Black child enrolled in the white elementary school in Conroe. “I integrated my town’s schools, a la Ruby Bridges, with the chief difference being that I was not escorted to my first day of school by federal marshals.”

The little girl proved an excellent student and recalls kind teachers and making friends. Still, she acknowledges and explores the tensions. Her mother remembers Annette breaking out in hives, “a thing I don’t recall.”

She does remember and relish the hours, seemingly endless at the time, making tamales with her female kinfolk for Juneteenth.

“This ritual was fitting, and so very Texan,” Gordon-Reed writes. “People of African descent, and to be honest, of some European descent, celebrating the end of slavery in Texas with dishes learned in slavery and a dish favored by ancient Mesoamerican Indians that connected Texas to its Mexican past; so much Texas history brought together for this one special day.”