The pages of Jesmyn Ward’s third novel, “Sing, Unburied, Sing,” smell of Mississippi.

Set in the same fictional town, Bois Sauvage, as her 2011 National Book Award-winning novel, “Salvage the Bones,” her latest fiction returns to tell again of family bonds, tested by unresolved trauma and unrelenting Southern poverty. She undergirds the sense of place with a seven-line epigraph from Derek Walcott’s “The Gulf.”

At the heart of “Sing” is Jojo, a 13-year-old narrator focusing on his budding manhood. His role model? Pop, whose days are spent taking care of his cancer-stricken wife, Mam, Jojo’s toddler sister Kayla, and to a lesser extent, his daughter Leonie, Jojo’s mother.

Ward, a Mississippian and Tulane University professor, excels with a narrative that knits together three generations with precision. So much is in the details: early on, she establishes Leonie’s place in the family with Jojo’s decision to address his mother by her first name.

“Sometimes I think I understand everything else more than I’ll ever understand Leonie,” he says to himself as he watches his mother fumble on his birthday with a tiny baby shower cake and “the cheapest ice cream, the kind with a texture of cold gum.”

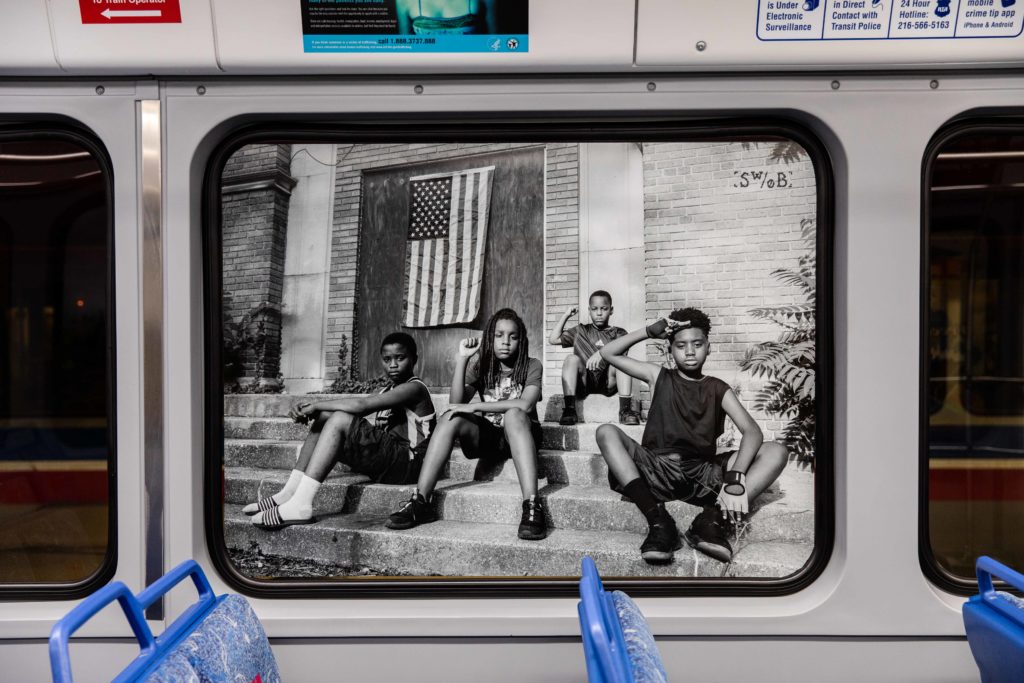

Both Jojo and Kayla are estranged from their father Michael, a white oil rig worker turned meth dealer, who’s finishing up a three-year bid at the state penitentiary. But when he’s released, Leonie insists that her two children and a family friend make the drive to bring him home. An unexpected visitor joins them on the journey, heightening a fraught trek.

The bond between Jojo and Kayla is the emotional core of the novel. Even Leonie knows she is on the outside looking in. When she spies them napping together, jealousy takes hold: “…a part of me wants to shake Jojo and Michaela awake, to lean down and yell so they startle and sit up so I don’t have to see the way they turn to each other like plants following the sun across the sky.”

Her efforts fluctuate in trying to be the mother she thinks her children deserve: one minute she’s hunting in the field for a homegrown remedy to ease her daughter’s sudden illness, the next she’s gone missing, with no clue to her whereabouts. Despite this, and despite her drug use, Leonie comes off as a sympathetic character. Her chapters are frustratingly good.

One compelling character, Leonie’s late brother Given, could have used more airtime. He appears in the book mostly as a ghost, haunting Leonie when she’s high. But he’s a dynamic figure, even from the afterlife, and Ward could have tucked in a bit more of his life before his untimely death.

Ward, 40, writes to tell the truth or, as she remarked to the National Book Award audience in 2011, “so that the culture that marginalized us for so long would see that our stories were as universal, our lives as fraught and lovely and important as theirs.”

This month, she received two pieces of recognition for her storytelling: one, being named a finalist again for the National Book Award and two, a selection as a MacArthur Fellow, with its $625,000 no-strings-attached award. (She responded to the latter on Twitter with a Prince gif.)

Ward has a page-turner on her hands, a slow burn of a book that dives deep into the waters of the South, exploring race and class in the context of memory. Of everything that happens to us, what leaves a scar? What holds us hostage?

Those scars are on full display in “Sing, Unburied, Sing,” and its colors are heartbreaking – and beautiful.