Seven years ago, Hidden Figures author Margot Lee Shetterly discovered a great untold story in her own hometown.

Shetterly, 47, grew up in Hampton, Virginia surrounded by “extraordinary ordinary people,” men and women who toiled daily at NASA’s Langley Research Center, including her own father. But it wasn’t until a holiday visit when her husband asked a question—prompting her father’s story about the black women who calculated the trajectories of the first orbital space flight—that the gravitas really sunk in.

“These women’s lives intersected so many of the signature moments of what we call the American century,” Shetterly noted, “so why has it taken decades for us to tell their story?”

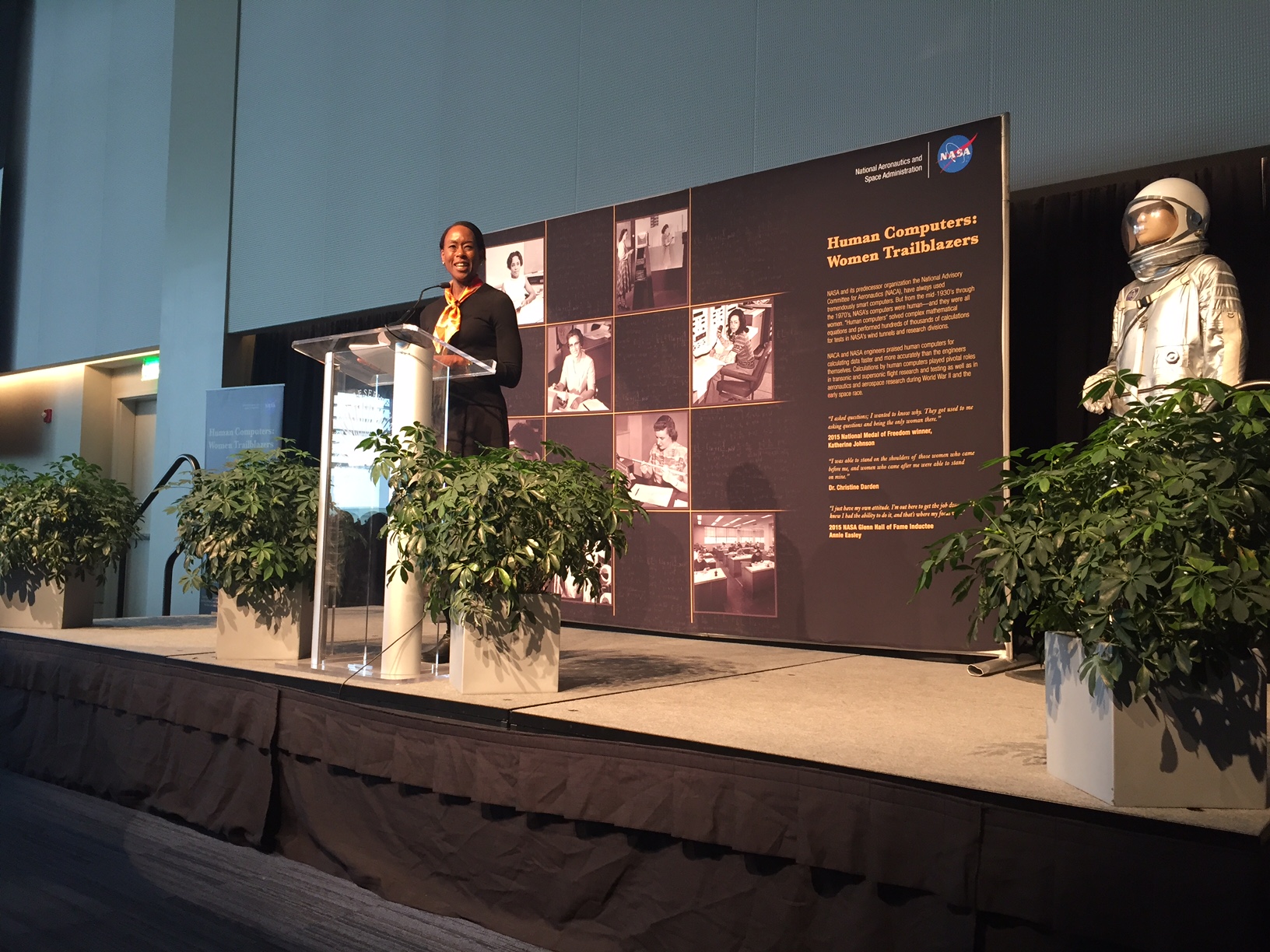

Flanked by colorful NASA backdrops and a full off-white astronaut’s suit, Shetterly shared her “aha moment” in front of a record-breaking crowd at Case Western Reserve University’s annual Martin Luther King Jr. convocation. Several schools bused in students. NASA employees milled around the lobby, passing out literature about other “hidden figures” and giving stickers to young people in attendance.

The four women at the center of Hidden Figures were NASA mathematicians who broke barriers—”intrepid women of science who also saw themselves as instruments of social change,” Shetterly said. “They exemplified your MLK theme this year of hope and solidarity.” Dorothy Vaughan was the first black supervisor in NASA history, heading up a team of “human computers.” Katherine Johnson worked with the Space Task Group, calculating the launch of astronaut John Glenn’s first orbit around the Earth, while Mary Jackson integrated the University of Virginia to become NASA’s first black aeronautical engineer. Christine Darden became one of the leading experts on sonic boom research.

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”

As Shetterly dug into the research, the number of women who had worked at NASA began to rise exponentially. “A thousand women working as professional mathematicians, getting up and going to work at NASA, every day for decades,” she said. “Why didn’t we turn them into professional role models and use them to pull generations of young people, particularly young women, into science careers?”

Johnson, as a black woman born in 1918 in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, had just a two percent chance of finishing high school and a life expectancy of 35. Today, she is a lucid 98-year-old. “These women had excellent educations at HBCUs [Historically Black Colleges & Universities],” the author said, “and when the doors opened, they were as prepared as well as anyone.”

Shetterly, herself comfortable with calculations, landed in the financial sector after graduating from the University of Virginia, working at investment banks J.P Morgan and Merrill Lynch, before switching gears to publishing. In 2005, she moved to Mexico City with her husband Aran, where they spent 11 years publishing an independent magazine, Inside Mexico.

Shetterly sold the Hidden Figures book proposal to William Morrow in 2014, and received a grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation to support the research. Almost immediately, Hollywood came calling. Within months, she was working as an historical consultant on the film adaptation before her book was even finished. It landed in theaters this winter and, to date, Shetterly has watched the movie six times and counting.

“I’m thrilled with how it translates to the screen,” she said, beaming. Academy voters agree with her — the adaptation has been nominated for three Oscars, including Best Picture.

So why did these black women remain in the shadows? Part of it was the classified nature of the work, Shetterly conceded. But the most egregious reason was the unrelenting segregation of the workplace itself, with separate offices, bathrooms and lunchrooms. The human computers wore skirts and heels every day, “their hedge against being mistaken for the cafeteria worker or the cleaning lady.”

Sexism also played its part. Computing was considered women’s work, Shetterly said, and defined as sub-professional. It often meant women solved the same problems and carried the same workload as their male counterparts, but were relegated to less pay, prestige and credit: “If today’s America gets a case of double vision when trying to focus its gaze on a black female mathematician or scientist, just think of the blind spot these women existed in sixty years ago.”

Of the four women Shetterly featured in the book, Johnson and Darden are still alive.

Last May, NASA honored Johnson’s three-decade career with a new 40,000-square-foot Langley research facility named for her. “I have always done my best,” she said at the ceremony. “At the time it was just another day’s work.”

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”

“It was very important to me that ‘American Dream’ be in the subtitle of this book,” Shetterly declared. “And the most important scene for me in the movie was the first one, where a little black girl in big glasses — like me — is standing at the blackboard factoring quadratic equations.”