by Lisa Nielson, Anisfield-Wolf SAGES Fellow at Case Western Reserve University.

I was taking an internet break from my pile of books in the National Library of Jerusalem this summer when a news article caught my eye. It reported the Jerusalem Pride Parade was going to kick off in about four hours — at 6 p.m. July 21, 2016 — in a park not far from where I was living. A year earlier, an ultra-orthodox fanatic stabbed six people at the march. One of the victims, Shira Banki, was 16 when she died. This time, the police were taking no chances. They blocked streets so participants could only join from certain points; they kept counter-protesters off the parade route and they prevented the family of the young girl’s killer from coming to Jerusalem.

I walked home, put on my purple “LGBT? Fine with Me!” shirt and joined the thin stream of people picking a way through the twisting back alleys and side streets of modern Jerusalem to reach the start. A crowd milled, waiting to go through security. Later I learned the organizers ran out of wrist bands. As I stepped into the park I found hundreds of people – shouting over pounding pop music, greeting friends, hoisting signs, draping flags. Some wore drag; some wore wings, some wore not much, but everyone seemed busy taking pictures with their phones. There were families with babies, soldiers in uniform, and visitors from outside Israel like myself.

My mother came out as a lesbian when I was 13. She did so at one of the toughest and most confusing times of her life, in conservative Salt Lake City. I remember being incredibly proud of her, yet too young to understand the importance of her decision. So my mom liked to sleep with women? Big deal.

Nevertheless, I found out we were not safe. Authorities might take me away from her; she could lose her job. Even worse, she could also be forcibly hospitalized. We knew a lesbian, I’ll call her Susan, who called a confidential hotline one night in desperation. The hotline worker called the police. We took care of her daughter while hospital staff gave her intensive drug and electro-shock therapy. Not long after her discharge, Susan killed herself – I never learned what happened to her child.

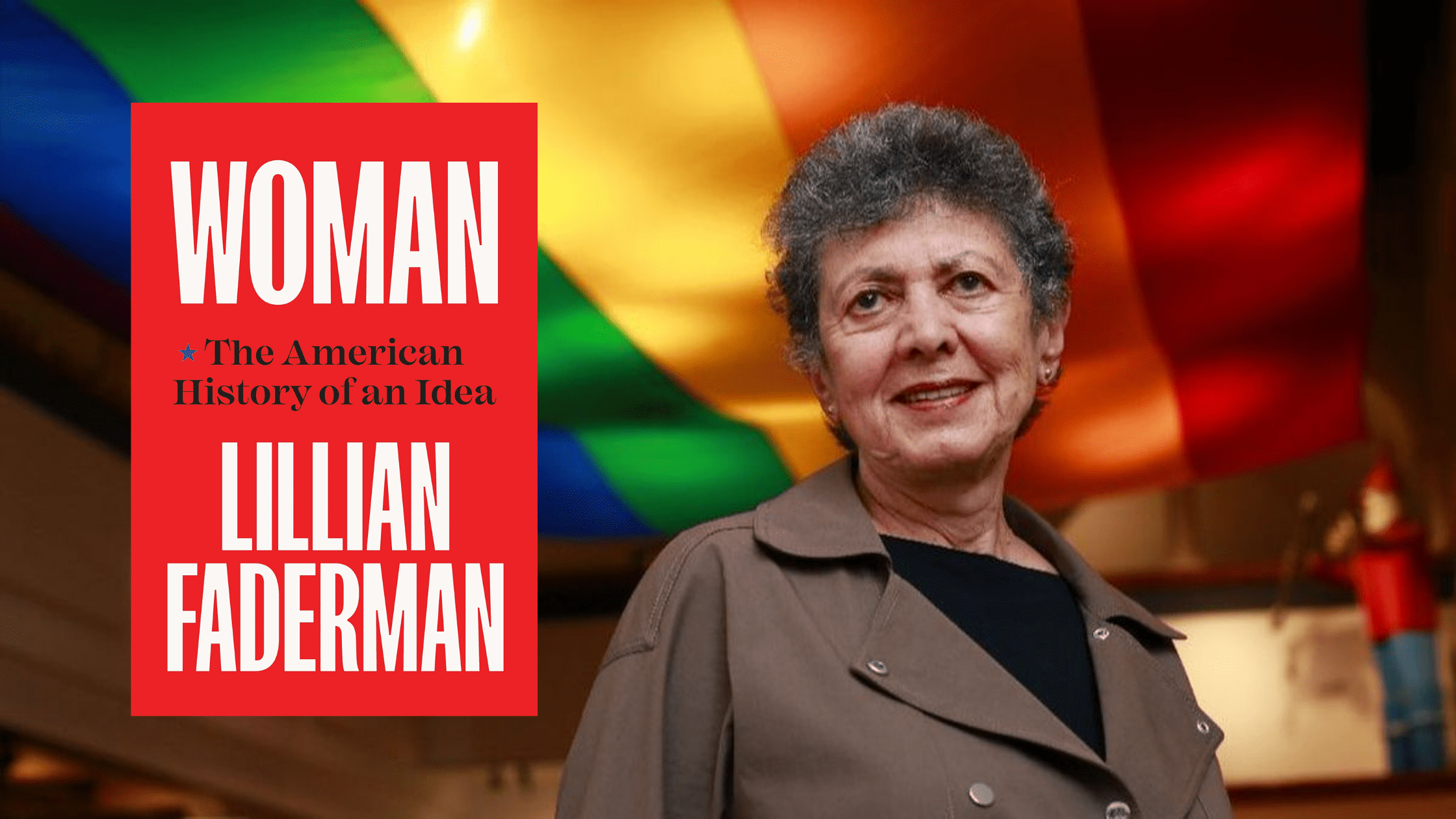

As the Anisfield-Wolf SAGES Fellow at Case, I read each new crop of winning books, and this spring I was especially thrilled to find Lillian Faderman’s book, The Gay Revolution, on the list. It was enlightening, sorrowful and uplifting. I had grown up in the movement and yet there was much I didn’t know.

At 16, I had the pink triangle on my bag, a “Stop Heterosexism” pin on my hat, and was reading Audre Lorde. While in college, I helped carry the banner in the first Pride Parade in my tiny town of Bangor Maine, and participated in early local meetings of PFLAG. I was vocal supporting my LGBT friends and celebrating National Coming Out Day when it was still new. At times, I was harassed or criticized for my stance; others simply assumed I was a lesbian and dismissed me. Both responses taught me a great deal, as well as my own privileged position.

I am not a lesbian.

Like all the other identities in my life, I skirt close to the edge without being part of any. My mother laughingly called me her “heterodyke” and a number of women in the community were interested in me, but I turned out to be (perhaps disappointingly) straight. It didn’t matter to my LGBT community at all, which taught me another valuable lesson about tolerance and acceptance.

As I wavered about joining the Jerusalem Pride parade that afternoon in the library, I thought about my personal history and the historical weight of Faderman’s book. But it was the notion of my students that decided me. What would they like to see? How could I bring this experience into the classroom?

Yet, as I joined the crowd, I realized I was there for a wholly different reason. This was my community. I needed to be there, for me. As we started to march, I started to cry, and the tension of two months of intense work in an armed city began to ease. I held out my phone so I could film every second. Sure, I took pictures for others, but to be honest, it was all for me.

Some 6,000 miles from my apartment in Cleveland, I had arrived home.

Lisa Nielson is the Anisfield-Wolf SAGES Fellow at Case Western Reserve University.