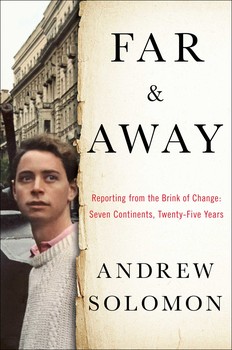

When Andrew Solomon went to Finland to promote The Noonday Demon, his ground-breaking 2001 book on depression, he landed on a leading morning television show.

The interviewer, “a gorgeous blonde woman, leaned forward and asked in a mildly offended tone, ‘So, Mr. Solomon. What can you, an American, have to tell the Finnish people about depression?’” the writer recalls in his newest work.

“I felt as though I had written a book about hot peppers and gone to promote it in Sichuan,” Solomon jokes in the leisurely and chatty introduction to Far & Away: Reporting from the Brink of Change: Seven Continents, Twenty-Five Years.

Clearly this 52-year-old writer, who won an Anisfield-Wolf Book Award in 2013, has serious wanderlust. Solomon has traveled to 83 of the 196 recognized nations in the world. “I’ve been to so many places, and seen so much, and sometimes it feels like a glut of sunsets and churches and monuments,” he admits.

But it is also clear that travel has helped form Solomon into a public intellectual. By the end of this book, he himself is setting off scandals in Ghana and Romania, largely via his reputation as an LGBT activist. Far & Away collects 28 essays from Solomon’s decades of globe-trotting, including one set in northern Bali called “Where Everyone Signs.” It is plucked from his chapter on deafness in Far From the Tree, his Anisfield-Wolf winner in nonfiction.

“I had started traveling out of curiosity,” Solomon writes, “but I came to believe in travel’s political importance, that encouraging a nation’s citizenry to travel may be as important as encouraging school attendance, environmental conservation, or national thrift.” A few pages later he elaborates, “When I was in Libya, the people I met who had an essentially pro-American stance had all studied in the United States, whereas those who were vehemently anti-American had not.”

As a young New Yorker studying in England, Solomon cops to some youthful callowness: “I confused, as many young people do, the glamour of being an outsider with the liberty to do or think whatever crossed my mind.” Serious travel taught the writer to grapple with ideas he would not have otherwise encountered: “When Chinse intellectuals spoke to me of the good that came of the Tiananmen massacre, when Pakistani women spoke of their pride in wearing the hijab, when Cubans enthused about their autocracy, I had to reconsider my reflexive enthusiasm for self-determination. In a free society, you have a chance to achieve your ambitions; in an unfree one, you lack that choice, and this often allows for more visionary ambitions.”

Today Solomon leads a highly political life at the helm of the Pen America Center, a venerable nonprofit that advocates for imperiled writers globally.

His new book has a dizzying array of datelines. The first essay, “The Winter Palettes,” stems from Solomon’s first reporting assignment abroad. In 1988, the British monthly “Harpers & Queen” sent him to the USSR to cover Sotheby’s first sale of contemporary Soviet art. It begins with a toast, and in a book of many toasts and parties, captures some of the intoxication swirled into art and social change.

“I am susceptible to that little moment of romance when a society on the brink of change falls temporarily in love with itself,” Solomon writes. “I’ve heard to same people speak of the great hope they felt when Stalin came to power and the hope they later felt when he died; others, of the hope they felt when the Cultural Revolution began and the hope they felt when it ended. . . Hope is a regular chime in political life.”

His last essay, “Lost at the Surface,” details a narrow escape from drowning while scuba diving off Australia. He wrote it last year for “The Moth.” Invariably, it is illuminating to look out through Andrew Solomon’s eyes – whether he is drifting in the open ocean or realizing in Cuba in 1997 that “If you want to get to know a strange country quickly and deeply, there’s nothing like organizing a party.”