Edwidge Danticat began her remarks in Cleveland by drawing attention to another artist, the painter Jacob Lawrence, whose migration series was on display last year at the Museum of Modern Art. Danticat, who has family in Brooklyn, New York, said she often walked the long rectangular room, soaking in the art as a way to reflect on the massacre at Mother Emmanuel AME Church in Charlotte, South Carolina.

“What kept me glued to these dark silhouettes is how beautifully and heartbreakingly Lawrence captured black bodies in motion, in transit, in danger, and in pain,” she said. “The bowed heads of the hungry and the curved backs of mourners helped the Great Migration to gain and keep its momentum, along with the promise of less abject poverty in the North, better educational opportunities, and the right to vote.”

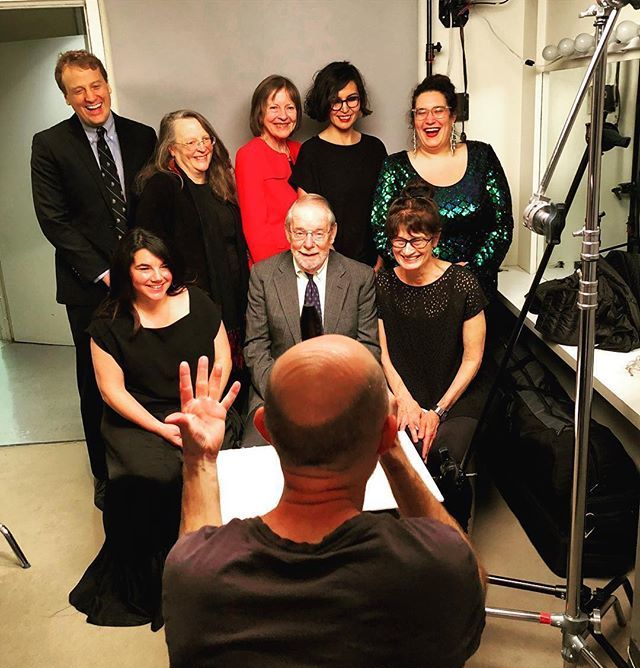

Danticat won a 2005 Anisfield-Wolf Book award for her novel “The Dew Breaker” about political violence in Haiti and the consequences in New York. She returned to Cleveland to speak at Case Western Reserve as part of the Cuyahoga County Library’s Writers Center Stage series.

Case President Barbara Snyder praised both Lisa Nielson and Kaysha Corinealdi, Anisfield-Wolf SAGES scholars at Case, for their work teaching and mentoring on campus. Snyder then turned the lectern over to Corinealdi, who introduced Danticat from the breadth of her own scholarship on the Caribbean diaspora. Read her introduction, below.

Over the years I have had the great joy and honor to read and also share with my students a number of our guest speaker’s works. I can still recall my first readings of Krik? Krak! (1995) and The Dew Breaker (1998) and how with each story I asked myself, who is this Edwidge Danticat? How can she capture in such a nuanced and unflinching fashion the nature of being a young girl in a new country, the voices of ordinary women and men caught in the middle of brutal geopolitical and national events, the daily making of diaspora by exiles and migrants, and the experiences of parents, children and lovers having to make impossible choices and hoping that in time, they will find forgiveness, if not from within, at least from future generations.

I am not ashamed to say that in reading these stories and many of Danticat’s later works, I would find myself both eager and afraid, jubilant and sad, to turn the next page.

Teaching Edwidge Danticat’s work has likewise proven to be an inspirational and humbling experience. Few authors have the skill to elegantly navigate between fiction and non-fiction. Indeed, Danticat is one of a select group of writers to be honored for her work in both genres. It is this ability to illuminate the fictions in history and the historical resonance in fiction that most impresses my students.

Through her intricate story telling and her acute awareness of the histories that live with us, and the histories that at times haunt us, Danticat also dares us to include ourselves, our most vulnerable selves, in writing, living, and remembering history. This semester, in a course inspired by Anisfield-Wolf Book Award winners, my students are reading Danticat’s memoir Brother, I’m Dying (2007). With a mixture of admiration and general curiosity, my students have wondered aloud about Danticat’s own journeys, her experiences with displacement, and her choice to write about love and responsibility in ways that crossed the boundaries of bloodlines and geography.

Today they had the opportunity to share some of these questions and observations with the writer herself, and in watching these exchanges I emerged an even greater fan of tonight’s speaker.

Before I turn over the stage to our speaker I must take the time to note some of her remarkable achievements. Edwidge Danticat is the winner of numerous awards, including the American Book Award (1999), the Anisfield-Wolf Book Prize in Fiction (2005), the National Book Critics Circle Award for Autobiography (2007), a MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant (2009), the Langston Hughes Medal by the City College of New York (2011), the One Caribbean Media Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature (2011), and her latest novel, Claire of the Sea Light, was shortlisted for the Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction (2014).

In addition to her literary achievements, our speaker has over the years put into practice the notion of activist artists and artists as public intellectuals. In particular she has spoken out against dehumanizing portrayals of Haitians and Haitian Americans in the U.S. media, shed light on the deplorable conditions of U.S. immigration detention centers, urged us to mourn and collectively denounce violence against black bodies in the Americas, and most recently, helped educate the U.S. public about mass deportations and denationalization targeting Haitians and Dominicans of Haitian descent in the Dominican Republic.

Through her literary and public intellectual and activist work, our speaker gives us much to aspire to as readers, students, scholars, and concerned citizens of the world.