by Sarah Marcus

Like many of my days spent teaching, today feels hard, but important. By 10 a.m. I’ve already had some awesome, small victories. A student ran upstairs 10 minutes before class to make sure that he understood what the word “vixen” meant and wanted to discuss if he could use it in a feminist context within his “Be A Man” poem. He told me that this felt like the biggest and most important question that he had all year. He caught the bus early so that he could be at school early to talk to me about it.

The “Be A Man/Woman” poem assignment originated from a powerful in-class discussion that we had about gender and masculinity. In my 12th Grade Creative Writing Class, largely due to the influence and materials of one of my incredible mentors, Daniel Gray Kontar, we have recently been examining Feminism and Hip-Hop. We are learning to identify poetic and literary devices through the analysis of classical poets and Hip-Hop poets. We are looking at the larger conversation that occurs in R&B music amongst emcees. We looked at ’80s and ’90s hip-hop feminists and we are now looking at and discussing the feminism and anti-feminism of Nicki Minaj. We are talking about objectification and authoring our own identities. We are talking about the double standards and negative connotations that come with women “acting like men” and vice versa. We began this unit by watching the documentary film MissRepresentation in order to provide context about how gender is portrayed in the media.

During one of our discussions about gender expectations and slut shaming, one of my senior girls says, “A master key is a key that can open any lock. That’s how we treat boys having sex. But, a lock that can be opened by any key is a bad lock. That’s how people look at girls.” Brilliant. Devastating.

We watch an interview with Nicki Minaj where she talks about how a man is a boss and a woman is a bitch when they try and get things done. We want to know what it means to be a successful businessman/woman. Some of my students have deeply held and extremely traditional beliefs about gender roles. We talk about how that is OK, if that’s what both people in a relationship want. We talk about how feminism means that you get to choose. We talk about consent.

My students, for the most part, are pretty invested. They are also super insightful. They are becoming educated consumers. I get emails and texts at all hours of the day and night with video clips or pictures that involve pop-culture that addresses feminist themes. As a teacher, this fills my heart with joy.

One day, we began a class with a short video from the #VogueEmpower Campaign to #StartWithTheBoys called “Boys Don’t Cry.”

During our follow up discussion, one of my girls says, “I would want my husband to tell my son to stop crying. I don’t want no sissy son. My daddy hit my mom because his daddy hit his mom. Not because someone told him not to cry or to stop acting like a girl.” I think being a good teacher means that everyone feels safe in your classroom, even when comments make your stomach turn. Everyone’s voice must be respected and valued. Everyone comes from different experiences. To model this care is what allows students to explore and challenge each other in a moderated space. So, I try to respond with the love and tolerance that I desperately want them to show each other. I say, “That’s a really interesting point. It makes sense to me that the act of simply telling a boy not to cry doesn’t necessarily make him into an abuser. Do you think that was the message in this video?”

We talk about life cycles. About what happens when we are not allowed to have or express emotion? What happens when we are punished for our emotions? How many people have ever bottled up their emotions and then it all came out at once in an angry explosion, raise your hand? All hands go up. I relate, too.

One student is deeply is offended by the video. “I would never do that,” he says, “That’s not fair.” I give them a brief history of #NotAllMen and then I give a race analogy. What does it mean to say, I wouldn’t say racist things, so the problem of racism doesn’t apply to me? What is our responsibility as humans? As advocates? What does it mean to say that you don’t see race, or that in your personal experience, that’s not how racism works? What is the danger in that narrow perspective? How does it perpetuate racism? Rape culture? We begin to scratch the surface of intersectionality.

We spend another class talking about whether there is such a thing as a “real” man or a “real” woman. Is “real” just our way of separating out how some people use their actions, beliefs, and attitudes to help others and some people use them to hurt others?

These themes are interwoven with videos like Buzzfeed’s #BlackLivesMatter “Things Black Men Are Tired of Hearing.”

One student responds:

Everyone wants to be black; everyone doesn’t want to be black. People want to be black when it benefits them. They try and show so much pride in them when we get a black president. They don’t want to show up for the million man march the next day. It’s not a choice to be black, it’s your life. You have to choose. To you what does that mean? Are you the thug on the street with a gun at your side dealing drugs or are you in school getting your education?

I love these kids. I really love them. I don’t need them to think like me, but I do need them to feel challenged to think deeply. They challenge me, too. Most of my students still want to know when I’m going to stop “holding [his abusive actions] over Chris Brown’s head, because he’s apologized like a million times, Ms. Marcus!”

One of my students aptly points out that if you are conditioned to have no emotion, if you are programmed that way, it isn’t possible to believe that other people have emotions. It’s not possible in this scenario to have empathy, because you feel nothing.

I talk about the importance of empathy and being sensitive and expressing emotion… how I personally believe that expressing emotion and the ability to be sensitive and empathetic is healthy and helps us act loving and tolerant towards one another. I say that true strength comes with showing people care and forgiveness.

The boy sitting next to me says emphatically, “But, Ms. Marcus! Isn’t your boyfriend a bodybuilder!?”

And I say, “Yes, he is! This is an excellent point.” I talk about the stereotypes I had in my head about what I thought it meant to be bodybuilder before we met. I told them about the assumptions that I made about how I thought that my partner must have defined masculinity based on my assessment of his social media pages. I told them that I almost didn’t give him a chance. How I thought he was a hyper-masculine “bro.” After all, how smart could you be if you cared so much about muscles? Bodybuilders (in my mind) were self-absorbed, obsessed chauvinists with a one-track mind. Unfair? Extremely. I thought that he had a whole lot of dudes drinking out of red cups in his pictures… He had a lot of memes about #squatting and #fitgirls… oy vey, I thought. No thanks.

But, throughout our correspondences he was smart and witty and thoughtful and attentive. He read all of my online articles and was able to make intelligent comments about them. My partner, like many men I’ve met in their late 20s, didn’t identify as a feminist (despite being one) until he met me. Today, he is an incredible and visible ally and advocate. I tell my students that he is the kindest, most compassionate, sensitive, chivalrous and emotionally advanced man I have ever met, and we get to talk about how a man can be all of those things. I tell my partner about our class discussion and he writes a beautiful, thoughtful response to the kids about what masculinity means to him. This is how “Be A Man/Be A Woman” poems happened. I knew we needed to creatively process these discussions.

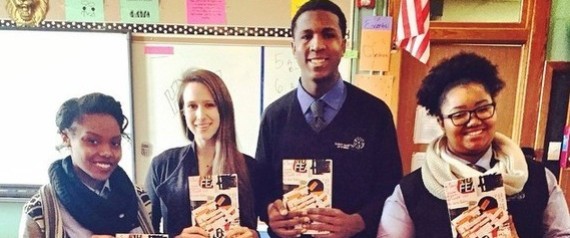

In regards to this morning, another one of my senior boys wrote a truly powerful poem about masculinity and orchestrated opportunities for audience participation. He even came to me after school last week to discuss my partner’s response to what it means to “be a man.” We went paragraph by paragraph. He was so interested in how someone could identify as both a very “masculine” bodybuilder and also as a feminist. This is a student who turns in no work and is constantly on the verge of being kicked out. I wrote a positive letter home, and when I went to put it in his file, I saw a long list of notes home about failing classes. This was his first positive home contact and he has been here for four years. Another one of my male (cis) seniors wrote a poem from the perspective of a young gay man. Kind of groundbreaking, right?

I was so invigorated by these wins. These dedicated and brave students. Then, I open my email from our school social worker to read that another one of my freshmen girls lost a family member to a fatal drive-by shooting. These types of emails are not uncommon. Recently, another one of my senior boys lost four family members in a brutal home murder. Sometimes it feels like you are doing so much, and then you realize that you are doing so little. These kids live in a reality riddled with violence that most of us can’t possibly begin to understand. I learn from their strength and fortitude. I try to grow from it. I am humbled and blessed to be able to do this job. So, when I feel like I’m having a tough day because my body hurts due to a slew of not fun health issues, I think about how my day isn’t actually tough at all. It’s all about my perspective and attitude. It’s never going to be as hard for me as it is for them. That’s why I teach. Because everyone deserves a chance. These kids, especially. I want them to have the tools to change the narrative. They are brave and they are empowered to author their own identities. Our actions matter. Teachers matter. Students matter. I want them to have a voice, to know their voice, and to use their voice.

Republished with permission by the author.

Sarah Marcus is the author of BACKCOUNTRY (2013, Finishing Line Press) and Every Bird, To You (2013, Crisis Chronicles Press). Her other work has appeared or is forthcoming in McSweeney’s, Cimarron Review, CALYX Journal, Spork, Nashville Review, Slipstream, Tidal Basin Review, and Bodega, among others. She is an editor at Gazing Grain Press and a spirited Count Coordinator for VIDA: Women in Literary Arts. She holds an MFA in poetry from George Mason University and currently teaches and writes in Cleveland, OH.