by Marilyn Williams Pringle

I never wanted my three children to be sent into in an environment where they would be exposed to racism or be treated differently because of the color of their skin.

During the 1970s, when my sister-in-law went to Valparaiso University, a predominately white school in Northwest Indiana, she endured countless racial incidents that made me fearful as my own daughters approached college age. Once, a carload of young white students chased her and her friends, shouting at them and calling them the N-word until they reached the safety of their dorm.

So while my children attended high school in Cleveland, I would tell them, repeatedly, “I don’t care what college you go to, but I’m sending my checks to an HBCU.” There, I felt they would be at least somewhat protected from the ugliness that often permeates higher education. I didn’t want them accused of being “affirmative action” admissions and I didn’t want them to be feel like they had something extra to prove. At an HBCU, they could learn in an environment where people would see their abilities first, their race second.

That was my experience at Wilberforce University in southern Ohio, studying as a first-generation college student. I can’t even remember who introduced me to Wilberforce as an option for college—a guidance counselor, perhaps? But I do know my reasons for saying yes to a historically black school.

I graduated from Shaw High School in East Cleveland and thought a predominately white university would contain too much culture shock, after growing up in a place where most people looked like me. I also knew I didn’t want to go to a mega-university, like Ohio State, and be lost in the crowd. Plus, I wanted to remain close to my mom, who was living alone as a widow two years after my dad died. I found out that I liked the Ohio cornfields and riding the bus into town.

At Wilberforce, I felt like I mattered.

If a student didn’t have their act together, the professors and staff would talk to that individual like their son or daughter. They would treat the student like family. And they would remind us, “Just because you’re at an HBCU, don’t think you’re getting an inferior education.” People had a lot of pride in Wilberforce. We didn’t have a football team, but homecoming was always a big event.

I hope Wilberforce can overcome their current enrollment challenges and remain open, because they have played an important role in educating African-Americans. As the oldest private HBCU, they teach students how to succeed, how to have the confidence and self-esteem that will help them compete with anyone. The HBCU experience is about more than academics. It’s about service. It’s about contributing. It’s about discovering who you are in an environment that truly wants you to succeed.

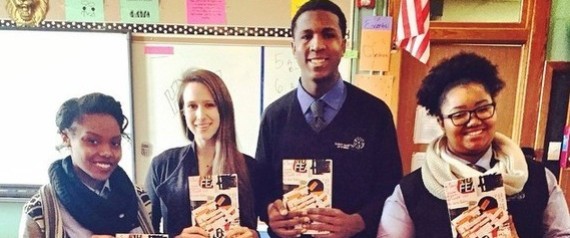

Two of my three children are graduates of HBCUs—Howard University in Washington, D.C., and Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach, Fla. (The third earned her bachelor and master’s degrees at a state university.) I’ve seen the difference the HBCU experience made in my daughters’ lives. When my husband and I first visited Bethune-Cookman with my youngest daughter, Olivia, I noticed the school motto etched into each doorway in the academic buildings: “Enter to learn, depart to serve.” I was sold. So was my daughter.

Marilyn Williams Pringle is a registered nurse in Cleveland. She attended Wilberforce in the early 1980s.