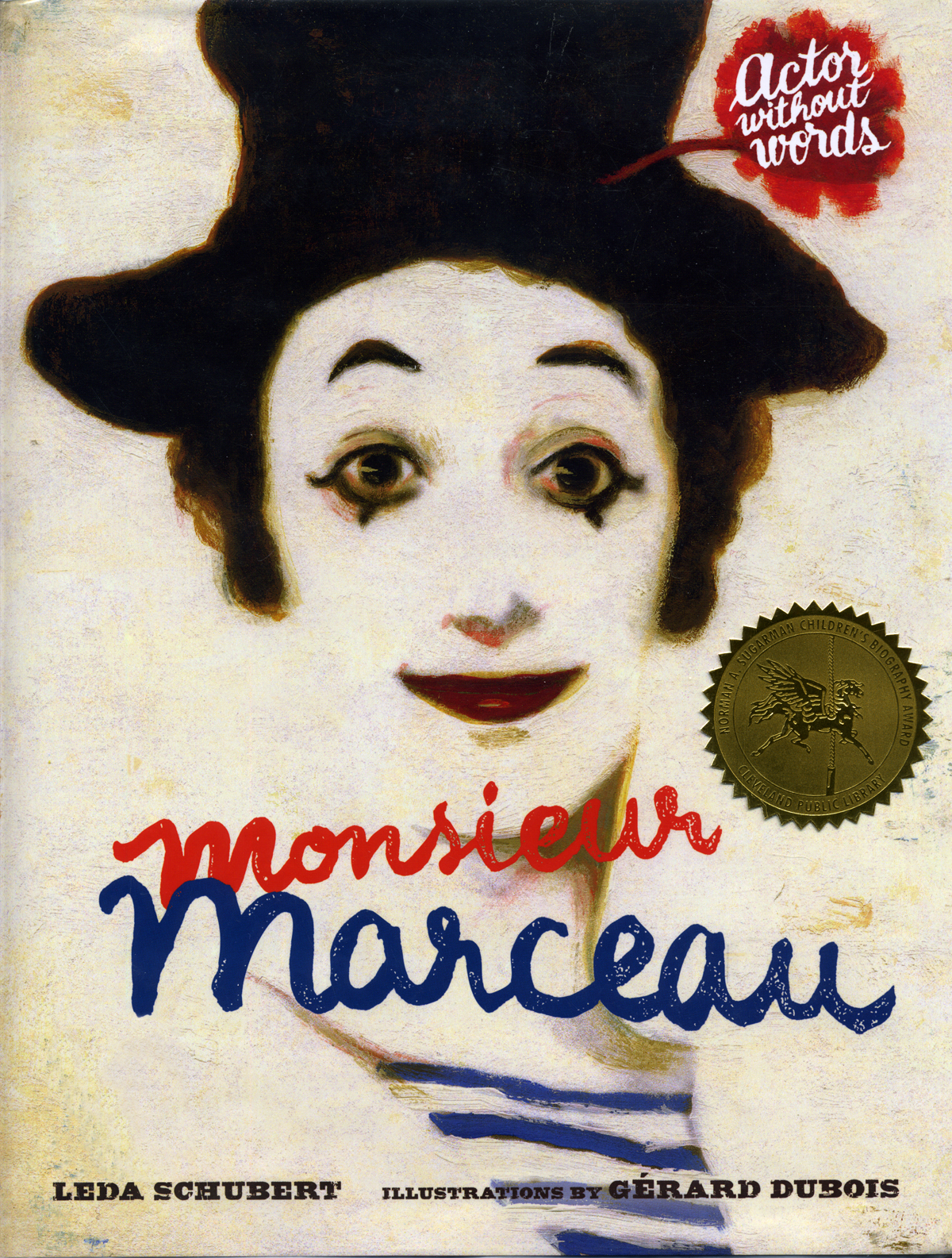

A standard picture book contains 36 unnumbered pages. “Monsieur Marceau” follows the pattern, but manages a wondrous, supple depiction of the legendary mime Marcel Marceau.

Thanks to the lyrical writing of author Leda Schubert and the evocative paintings of illustrator Gérard DuBois, “Monsieur Marceau” has won the Norman A. Sugarman Children’s Biography Award, a biennial prize conferred by the Cleveland Public Library. During a ceremony in late May, two Sugarman honor books were recognized along with “Monsieur Marceau”: “Face Book,” by Chuck Close, and “Temple Grandin: How the Girl Who Loved Cows and Embraced Autism Changed the World,” by Sy Montgomery.

Schubert’s book dwells on Marceau’s art but also touches upon his heroism. She notes that during the Nazi occupation of his country, “He led hundreds of Jewish children from an orphanage in France to safety in Switzerland. They pretended they were going on vacation, often disguised as boy scouts.” After the war, he began his remarkable theatrical career.

“Children’s biographies aren’t like other narratives that youngsters encounter in school, on television, or in video games,” said Arthur Evenchik, the award ceremony’s keynote speaker. “After all, we know how a biography is going to end: the subject will achieve success and make a difference in the world. That’s where the story is heading. And yet, biography is still a suspenseful art form, because we don’t know how that person achieved success.

“How did Marcel Marceau, who spent his teenage years as an underground resistance fighter, become the world’s most famous mime?” Evenchik asked, then drew his listeners’ attention to the subjects of other Sugarman books. “How did George Washington Carver, the son of a slave, become one of the leading agricultural researchers of his day? How did Temple Grandin, a person with autism, become a renowned animal scientist, author, and public speaker? From a distance, these seem like miraculous transformations – and indeed they are. But children themselves are always in the process of becoming, and reading biographies is an ideal way for them to explore and reflect on that process.”

Evenchik, who coordinates the Emerging Scholars Program at Case Western Reserve University, praised the quality of the books honored by the Sugarman jury since the award’s inception in 1998. He also celebrated the ever-growing diversity of their subjects. In these biographies, he said, “children can find stories of gifted, resilient people who look like them, whose struggles resonate with theirs,” and also “explore the lives of people who are different from themselves, or who seem to be different—people they might never have known about otherwise, whose struggles would have remained beyond their comprehension.”

Unfortunately, Evenchik added, diversity is all too rare in children’s literature. Citing a study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin, he noted that out of 3,200 children’s books published in 2013, 93 were about Africans or African-Americans, 69 were about Asian Pacific or Asian-Americans and 57 were about Latinos.

To strengthen his case for the value of diversity, Evenchik quoted Christopher Myers, a children’s book author and illustrator. Myers has written of the validation that comes “from recognizing oneself in a text, from the understanding that your life and the lives of people like you are worthy of being told, thought about, discussed, even celebrated.” Yet Myers also insists that multicultural books are not simply “mirrors that affirm readers’ own identities.” Children, he writes, see books “less as mirrors and more as maps. They are indeed searching for their place in the world, but they are also deciding where they want to go. They create, through the stories they’re given, an atlas of their world, of their relationships to others, of their possible destinations.”

Evenchik linked this insight to the Sugarman biographies, describing them as “a collection of atlases.” He paid tribute to Joan Sugarman, a children’s librarian, who established the prize to honor her late husband, and he commended the Cleveland Public Library, its director Felton Thomas, and the jury for their work.

“I’ve been coming to this ceremony for a number of years and I have never heard things put so well,” said Joel Sugarman. Jury Chair Annisha Jeffries, the library’s youth services manager, was visibly moved: “I can’t talk about it. Thank you, Arthur.” And artist DuBois, who had traveled from Montreal to Cleveland for the ceremony, praised Evenchik’s careful appreciation of details in the illustrations, especially one in which young Marcel mimics Charlie Chaplin for a trio of friends and a little dog.

Attending via Skype, writer Schubert beamed from her home in Plainfield, Vermont. “It is gratifying to have hard work rewarded.” Answering a question from one of the jurors, Schubert explained that she got the idea for the book from her agent. As she worked on it, she drew on her experience taking a class in mime during her senior year of college.

Deborah McHamm, founder of A Cultural Exchange, told Schubert that she had distributed copies of “Monsieur Marceau” to a group of African-American high school students who were studying how one individual can make a difference to a community. “And they love it,” she reported.

Annisha Jeffries

May 28, 2014

Karen, thank you for your words and for joining us in this marvelous celebration that spotlights the most prestigious biographies for children. Here’s to 2016!

nancy sugarman

May 30, 2014

It was wonderful to hear about Mr Evenchik’s remarks. My mom, who created the award, would have especially appreciated them as they align fully with her vision, and expand it further. I wish I had a copy of the full address.