Every afternoon, I wait in my children’s grade school library with the other parents for pick-up. The principal reads off students’ names over the loudspeaker, the signal that they are dismissed and can meet us in the library.

Every day, without fail, the principal stumbles over Ayanna, my six-year-old daughter’s name. She tries “Ah-yanna,” “I-yanna,” “E-yanna”—every pronunciation except the correct one. (It’s “A-yahn-na,” in case you’re wondering.)

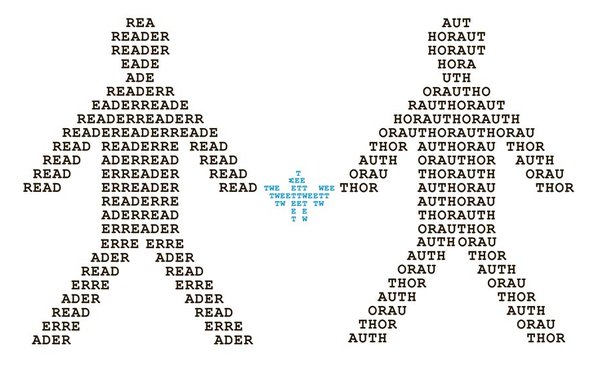

As a black mother, I felt pressure—mostly from well-meaning relatives—to give my daughter a racially ambiguous name, one that was simple and easy to pronounce. Too many vowels or even one apostrophe meant trouble. I chose “Ayanna” after reading it in an Eric Jerome Dickey novel and loving that it means “beautiful flower” in Hebrew.

My husband and I have not regretted our decision, but I was brought up short reading Nikisa Drayon’s post in the New York Times titled, Will a “Black” name brand my son with mug shots before he’s even born? The writer is seven months pregnant and fretting over giving her son an “ethnic” name like Keion:

“The father of my child recently told me of his wish to name our son Keion, after his childhood best friend. I was nothing short of horrified. In my opinion, ‘Keion’ is identified as a ‘black’ name. My two best friends politely asked, in unison, ‘Don’t you think it sounds too ethnic?’ And I cannot forget my brother’s blunt, stinging remark, ‘Hell, no … way too ghetto. You guys need to revisit the baby books.’”

So Drayton Googles the name to learn more about its provenance and is confronted instead with mug shots of various “Keions.”

“Contemplating baby Keion led me straight to a a black mother’s biggest fear, mingling inside me along with the common aches and pains of motherhood,” she writes. “My unborn son, a seven-month old fetus, could have all the world’s unspoken markings of a criminal — the wrong skin color and the wrong name.”

While I was conscious about how freighted a name can be, our choices for our daughter and son Thomas were personal, not fearful. We gave them names that sounded strong, had meaning for our family, and that would convey some idea of the hopes we held for them. Being worried that an employer will toss their resume after seeing a “black” name is a concern – one that sociologists continue to investigate. But should such caution be determinative? Let us know your thoughts.