One of my close friends, Shanelle Smith, shoved a thick book in my hands as we met for lunch. “You have to read this.”

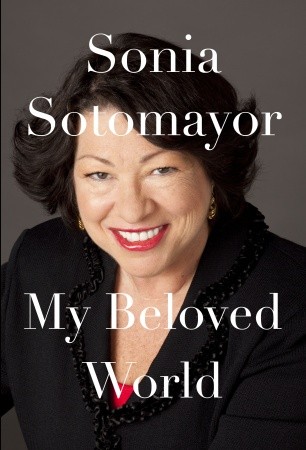

It was upside down; I flipped it over. U.S. Supreme Court justice Sonia Sotomayor beamed from the cover. “It’s very good,” Shanelle said, tapping the cover of My Beloved World for emphasis. “It’s my Lean In.”

Back in March, Shanelle and I had talked at length about Sheryl Sandberg’s “call to action” for working women as part of our informal book club. The child of two auto factory workers, my friend was turned off by Sandberg’s “middle class to riches” story, peeved that Sandberg had never met some of the barriers that low-income working mothers encounter. (Sandberg’s “working mom confession ” that her child had lice while on a private jet evoked zero sympathy.) Most women reading Lean In would never see the boardrooms Sandberg frequents, but I found enough truth nuggets to make it worthwhile.

Unlike Sandberg, Sotomayor isn’t dispensing career advice. The first Hispanic and only the third woman on the U.S. Supreme Court makes it clear that her story is personal.

Readers looking for a view into the inner workings of the Supreme Court will be disappointed. Sotomayor ends the book after her appointment to the U.S. District Court in 1992, calling it “inappropriate” to reflect on a journey still taking shape. That judiciousness has gotten her far in life.

Even without contemporary elements, her story is strong. Growing up with an alcoholic father who stayed sober just long enough to prepare dinner every night and a mother who worked long hours to avoid arguments, Sotomayor became self-reliant at an early age. Diagnosed with diabetes at 7 years old, she learned how to give herself daily insulin injections.

Her diabetes also spurred her career ambitions; on a visit to the doctor she received a pamphlet on careers she could aspire to as a diabetic. She noticed that a detective — an occupation the 10-year-old Nancy Drew wannabe considered her path to becoming a judge — was not on the list. She was undeterred. The pamphlet incident is now her go-to anecdote whenever she speaks to the juvenile diabetes crowd.

Sotomayor reminds readers repeatedly that she has reached the height of her career precisely because of her background, not in spite of it. She believes her devotion to her community guided the “small, steady steps” that led to the Supreme Court. She writes about her years at parochial schools in the Bronx, where she first learned the joy of passionate debate, and her study at Princeton and Yale Law School, where she learned to advocate for diversity and move in the world on a grander scale.

“Until I arrived at Princeton, I had no idea how circumscribed my life had been,” she writes, “confined to a community that was essentially a village in the shadow of a great metropolis with so much to offer, of which I’d tasted almost nothing. I honestly felt no envy or resentment, only astonishment at how much of a world there was out there and how much of it others already knew.”

As she ascended in her career, first as an assistant district attorney and then as a private practice lawyer, her drive had ramifications for her personal life. She writes about the collapse of her marriage, noting that it was an amicable split and she remains friends with her former husband to this day. As for having children, Sotomayor took pleasure in being the “fun aunt” instead of having children herself: “The idea of another life utterly dependent on me, the way a child needs his mother, didn’t seem compatible with the professional necessity of living at this punishing pace.”

Reading this book in 2013, it’s good to remember that women of Sotomayor’s generation broke barriers as the first minorities to attend and graduate from institutions that had only recently started affirmative action practices. She detailed several instances of “casual” racism/sexism: the school nurse questioning her acceptance to Princeton; a law firm recruiter pushing her to admit that affirmative action is destructive; judges calling her “honey” in the courtroom. In spite of these slights, Sotomayor remained focused; her grit thrilled me.

Each chapter is a love letter to the values of hard work and dedication. As Sotomayor told committee members before her appointment to the federal bench: “I’m not intimidated by challenges. My whole life has been one.”

For readers who want to know what it was like to be nominated for the Supreme Court, here’s an excerpt from her interview with Oprah earlier this year: