American philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah is not allowed into China.

He mentioned this fact at the end of his well-attended March talk in Cleveland, noting he is unwelcome because of his support of Liu Xiaobo, a writer and political activist who won the Nobel peace prize in 2010. At the ceremony in Oslo, Liu was represented by an empty chair.

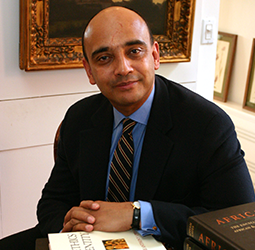

Appiah, a Princeton University professor, won an Anisfield-Wolf prize in 1993 for his book, “In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture.” Today he is president of the PEN American Center, whose home page features a vibrant photo of Liu, with the statement “jailed for writing seven sentences in China” and an invitation to view his case.

“Many, many more writers would be in prison today if we weren’t constantly popping off about it,” Appiah said of Liu’s incarceration. “Still, we haven’t managed to get him out.

“Chinese people complain to me about my regular complaints about Chinese human rights,” Appiah told several hundred listeners assembled in Severance Hall for his lecture on making moral revolutions. “I say, ‘Don’t complain about my complaint – complain about us, the United States.’”

This robust dynamic is caught, Appiah writes, by Thomas Jefferson, who referred to “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” in the American Declaration of Independence. This is “why the nation’s honor can be mobilized to motivate its citizens,” Appiah writes in his 2010 book, “The Honor Code: How Moral Revolutions Happen.”

His latest book is a scholarly and elegant examination of three practices—dueling in 18th Century England, foot binding in China, and Britain’s transatlantic slave trade—and how each came to a decisive end. All collapsed fairly abruptly.

“Whatever happened when these immoral practices ceased, it wasn’t, so it seemed to me, that people were bowled over by new moral arguments,” Appiah writes. “Dueling was always murderous and irrational; foot binding was always painfully crippling; slavery was always an assault on the humanity of the slave.”

Still, foot binding, which thrived for a millennium, ended in the span of a generation: Political scientist Gerry Mackie reports that “the population of Tinghsien, a conservative rural area 125 miles south of Peking, went from 99 percent bound in 1889 to 94 percent bound in 1899 to zero bound in 1919.”

In his book, Appiah calls this “the great unbinding” and attributes it to Christian missionaries campaigning against the practice combined with an awakening of national honor. The Chinese elite were increasingly shamed that outsiders condemned the practice as backward.

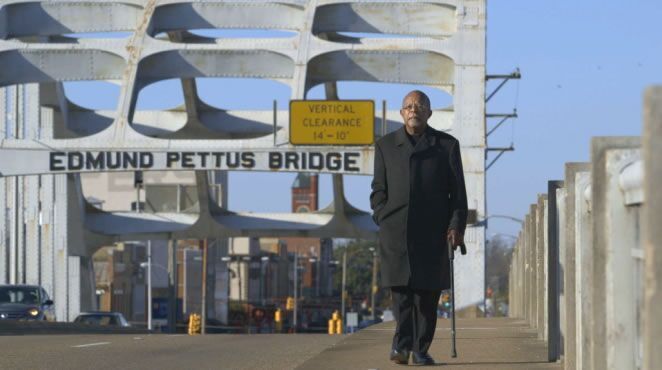

But as he gave the F. Joseph Callahan Distinguished lecture, Appiah did not dwell on foot-binding. He spoke, softly and forcefully, about cracks in U.S. national honor: 25 percent of the world’s prison population incarcerated in a country with four percent of the global population, and a lack of “democratic discourse” over drone strikes abroad, which Appiah said, had “killed huge numbers of absolutely innocent people, more than were killed in the World Trade Center.”

In sampling historic moral revolutions, Appiah cited Supreme Court Justice Anthony Scalia, John Locke, Thomas Aquinas, Aristotle, “the Bernie Madoff problem” and the 1792 novel by Frances Burney, “Cecilia.” He ranged fluidly across cultures and centuries.

Kenneth F. Ledford, professor of history and law at Case Western Reserve University, praised Appiah as “a massively productive scholar and one of the leading intellectuals in the United States.”

Appiah suggested that U.S. students—such as those at CWRU—were bound up in the nation’s honor, and the beneficiaries of “one of the best university systems in the world.” He expressed optimism that his listeners could be instigators of the next moral revolution.

“When you point out that people aren’t living up to their standards,” Appiah concluded, “you are appealing to their national honor, which, by the way, is what was crucial to the ending of foot binding.”