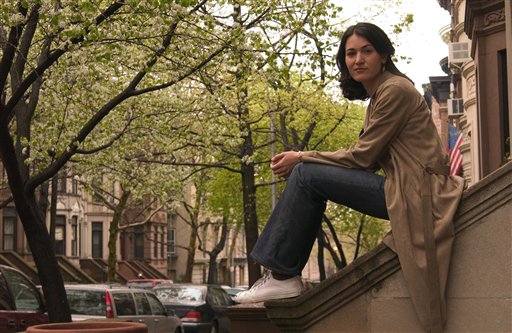

Each week, we’ll be helping you to get to know our winners better (what a great bunch they are) and highlighting the best of their work, interviews and essays. This week we’ll be focusing on Nicole Krauss, 2011 winner for fiction.

Even some of the most celebrated writers of our time struggle with doubt from time to time. How do they know if their work will resonate with readers? Do they aim for writing an award-winning book each time they sit in front of the keyboard or do they just wish for an authentic voice or story to guide them to completion? Nicole Krauss, author of three novels and a National Book Award finalist, wrote an unflinchingly honest essay on her story writing process and whether she ever feels a story will be successful as soon as she starts:

I begin my novels without ideas. I don’t have a plot, or themes, or a sense of the book’s form. Often I don’t even have a specific character in mind. I begin with a single sentence of no great importance; it almost certainly will be thrown away later. To that sentence I add another, and then another. A little riff emerges. If it’s going well–and it’s hard for me to say exactly what going well means, beyond the writing feeling authentic enough not to require immediate erasure–I’ll continue this sort of aimless unspooling. If I’m lucky, as the paragraphs accumulate, a compelling voice will emerge. Though often I will write twenty or thirty pages before I realize that in fact the voice lacks what might be called the “Pinocchio” element: the chance of becoming truly alive and “real.”

It’s unnerving not to know what I’m writing, or why, or where it will go. Scary, even, as time passes, and more and more work accumulates without an accompanying sense of clarity. A hundred or even two hundred pages in, and I am more lost than ever.I find myself worrying constantly that the work will fail. In my last novel, The History of Love, the potential of that failure became, itself, a theme of the novel–one of the main characters, Leo Gursky, is a failed writer.

Great House is my third novel, and so when I began it I already had some sense of what my writing process would be like. Yet my uncertainty was more acute than ever. The starting points I chose, which I knew would have to converge and cohere, were almost impossibly remote from one another. From out of all the early writing, four voices emerged, each with its own story: an American writer, Nadia, who has been writing for twenty-seven years at a desk she inherited from a Chilean poet who later disappeared; an overbearing Israeli father addressing his estranged son who has returned home after decades abroad; a retired Oxford don, who, in the final years of his wife’s life, discovers a secret she kept from him all their marriage; and a young American woman who tells the story of a Hungarian antiques dealer and his two adult children, whom she comes to live with in a darkly magical Victorian house in London. I had four different paths, and all I knew was that 1) I wanted to understand who these people were and what had made them that way, and 2) woven together, their stories could make a solid and intricate whole, that their juxtaposition would reveal patterns, and form a complete architecture–even, or especially, if I couldn’t anticipate that architecture. I was building a house–a city–without a blueprint.

Read the rest of the essay here in the essay, On Doubt.