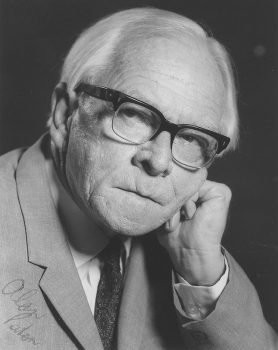

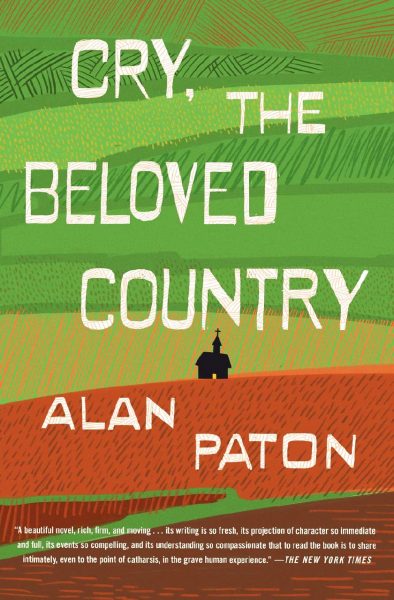

A white South African of British descent, Alan Paton wrote what is considered one of the great African novels in English. His mother was a teacher and his father was a civil servant, and after growing up in Pietermaritzburg he attended the University of Natal. Paton taught school for a decade, then switched careers in 1935 to head Johannesburg’s Diepkloof Reformatory, home to 650 black youths who had been labeled “delinquent” by the authorities. As principal he liberalized the reformatory’s regulations, giving inmates greater freedom and respect. His interest in social work stemmed in part from his conversion to the Anglican faith and his growing interest in racial justice. When his first novel, Cry, the Beloved Country, was published in 1948, the reviews hailed it as “beautiful and profoundly moving . . . steeped in sadness and grief but radiant with hope and compassion.”

The book’s protagonist is Stephen Kumalo, a Zulu priest who travels to Johannesburg from the countryside in search of his sister and his son. When he arrives, he discovers that his sister has been forced into prostitution and his son has fled after being involved in the murder of a white man. In the book’s most famous passage, Paton warns of the specter of large-scale racial violence: “Cry, the beloved country, for the unborn child that is the inheritor of our fear.” Not a simple political allegory, Paton’s novel contains layers of social and spiritual complexity and ends with the hope of reconciliation between black and white South Africans.

Cry, the Beloved Country has been translated into 20 languages and has sold 15 million copies. It was adapted into a 1949 play, Lost in the Stars (with songs by the composer Kurt Weill), and filmed in 1951 and with James Earl Jones as Kumalo in 1995. Paton, who eventually left his job to write full time, also became a political activist. In 1953 he helped found the Liberal Party, of which he was the first president. The party, which advocated universal voting rights and nonviolence, was banned in 1968 when the South African government prohibited all multiracial parties. For most of the 1960s Paton was forbidden to leave the country, but he continued to write, producing a second novel, seven works of nonfiction, and a play. None, however, is as well known as Cry, the Beloved Country, which he said was written “to influence my fellow whites.” Toward the end of his life, Paton faced significant criticism for opposing economic sanctions against South Africa’s apartheid regime, which he believed would harm poor blacks.

Contributed By: Kate Tuttle