Poet Shane McCrae was born in Portland, Oregon, and grew up mostly in Texas and California. “I failed every class from sixth grade up,” he once said, but the poetry of Sylvia Plath smote him one afternoon he remembers perfectly, when he was a teenager, Oct. 25, 1990. He has been writing since, both dropping out of high school and earning a law degree from Harvard University along the way.

In between, McCrae picked up his G.E.D., attended Chemeketa Community College, graduated from Linfield College in McMinnville, Oregon, then earned both an M.A. and an M.F.A. from The University of Iowa. He was the first in his family to graduate from college.

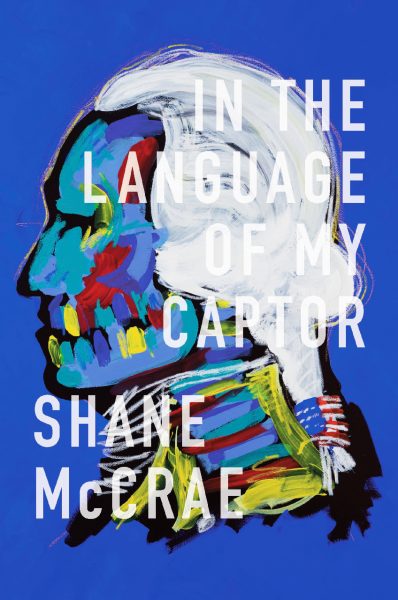

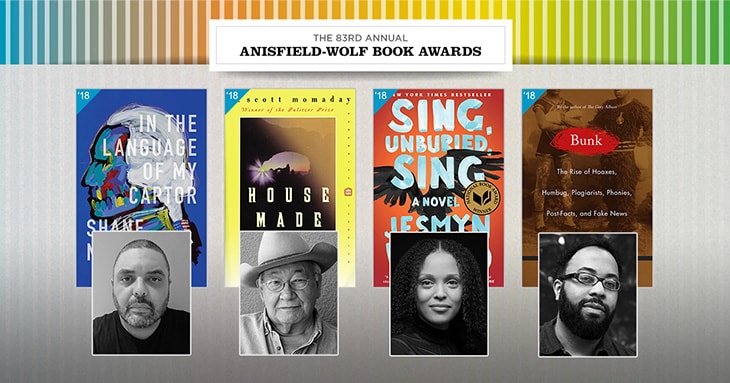

His fifth collection of poetry, In the Language of My Captor, is a book about freedom told through stories of captivity. In its three sections, the reader finds prose memoir and poems in historical persona, including the voice of Jim Limber, the mixed-race son whom Jefferson Davis adopted during the last year of the Civil War. McCrae is interested in the connections between racism and love.

“These voices worm their way inside your head; deceptively simple language layers complexity upon complexity until we are snared in the same socialized racial webbing as the African exhibited at the zoo or the Jim Crow universe that Banjo Yes has learned to survive in (‘You can be free//Or you can live’),” writes Anisfield-Wolf Juror Rita Dove. “As uncomfortable and, yes, sad as it makes me, I am profoundly grateful that Shane McCrae wrote it.”

Joyce Carol Oates, who serves on the jury with Dove, calls the book “powerful, unflinching, ingenious in plumbing the depths of the past in search of meaning that endures and prevails.”

In the Language of My Captor was also a finalist for the National Book Award. McCrae wrote it while teaching creative writing at Oberlin College in Ohio. In the fall of 2017, he accepted a position on the faculty of Columbia University in New York.

When McCrae’s first poetry collection, Mule, was published, he gave an interview to the Cleveland State University Poetry Center. “Each person is a world,” McCrae said, “and I know people are changed individually by poems, and then they take their changed selves out into the world, and consequentially that initial change ripples outward.”

Known for addressing thorny topics in lines that are “cool, easygoing and deep,” as one critic put it, McCrae pays exquisite attention to meter, punctuation and line breaks. He told the Public Broadcasting System, “I concentrate on the logic of the poem itself as a thing, rather than the message of what the poem is doing.”

Working in this vein, McCrae won a Whiting Award in poetry and a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. “For me, writing into history is a way to grapple with the terrifying certainty of the present,” the poet said in a 2013 conversation hosted by PEN America. “That is, the more one studies and writes with history, the more often one discovers that apparently large and important human developments — a lot of things most people would call ‘progress’— are superficial.”

McCrae lives in Manhattan with his wife Melissa and their daughter Eden, who is seven. He has a son, Nicholas, 14, who lives in Sherman, Texas, and a daughter, Sylvia Teeters-McCrae, 23, who lives in Portland. She was named for Sylvia Plath.